The irony isn’t lost on me that, considering I now devour more Korean cinema than any other countries output, unlike Hong Kong and Japan my first taste of it didn’t have me hook, line, and sinker. If anything, my introduction to the world of Korean cinema left me equal parts perplexed, but with an unshakable feeling that I wanted to see more. Looking back now I think I know why. While I’d gotten into Hong Kong and Japanese cinema when their Golden Era’s had already long past, leaving a seemingly unlimited back catalogue to explore, in the case of Korea my first taste came just as it was on the cusp of entering into its own Golden Era (or in other words – what would popularly become known as ‘The Korean Wave’).

The irony isn’t lost on me that, considering I now devour more Korean cinema than any other countries output, unlike Hong Kong and Japan my first taste of it didn’t have me hook, line, and sinker. If anything, my introduction to the world of Korean cinema left me equal parts perplexed, but with an unshakable feeling that I wanted to see more. Looking back now I think I know why. While I’d gotten into Hong Kong and Japanese cinema when their Golden Era’s had already long past, leaving a seemingly unlimited back catalogue to explore, in the case of Korea my first taste came just as it was on the cusp of entering into its own Golden Era (or in other words – what would popularly become known as ‘The Korean Wave’).

The funny this is, I’d often waxed lyrical about how fantastic it must have been to have experienced the classics of Hong Kong and Japan at the time they actually came out. Now in 2018, I understand that identifying a countries output as its Golden Era is something that can only be done from the viewpoint of looking back, and is rarely something that can be labelled in the present moment. With the benefit of hindsight, I would say the 15 years spanning 1999 – 2014 were Korea’s Golden Era, and they were years that I was lucky enough to be around for the same way I’d wished I was around for Hong Kong and Japans.

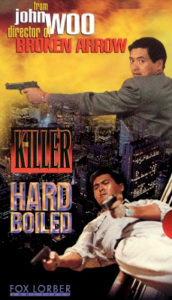

However when I viewed my first Korean movie back in 2001, I somehow felt that I’d been a victim of false advertising. At the time I’d been devouring Hong Kong action cinema like it was going out of fashion, and one of my most revisited purchases was a 2-DVD box set released by Fox Lorber of John Woo movies, which I’d imported from the States. The movies in question of course, were The Killer and Hard Boiled, and as an introduction to John Woo, it was impossible to beat (I’d spend several of the following years attempting to track down new copies of the Criterion releases of both titles, but that story is for another time).

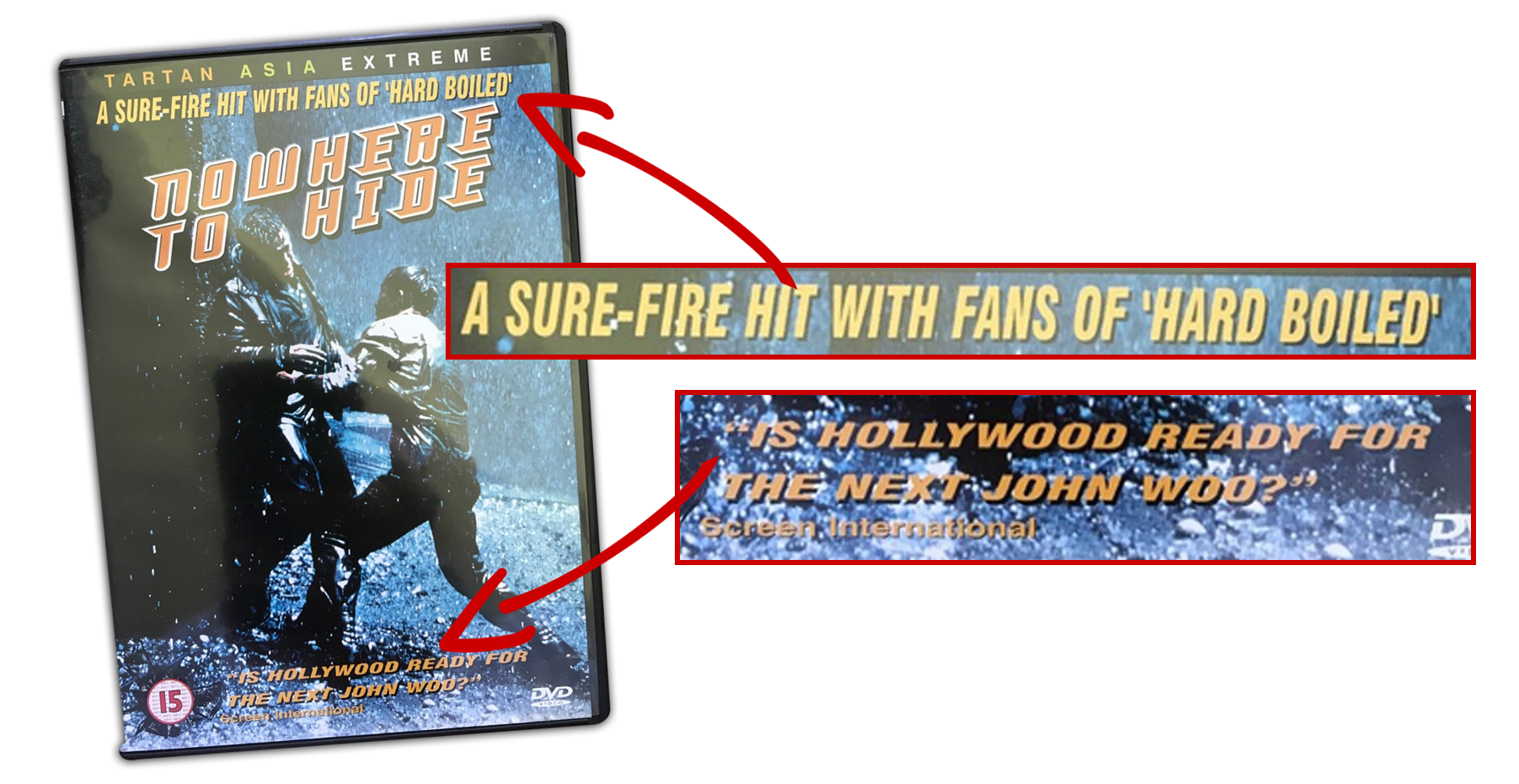

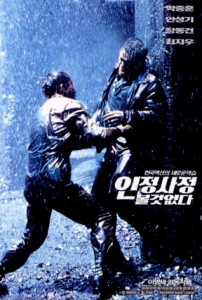

So you can likely imagine my delight, when local UK distributor Tartan Video added a title to their slate, that came with a cover proudly announcing – “A SURE-FIRE HIT FOR FANS OF ‘HARD BOILED’” and “IS HOLLYWOOD READY FOR THE NEXT JOHN WOO?” I didn’t care if Hollywood was ready or not, but I certainly was, and the image of 2 men brawling in a torrential downpour, which the quotes were splattered over, only sealed the deal. The movie in question was Nowhere to Hide, and despite its 2001 DVD release in the UK, it was actually made a couple of years prior, in 1999.

It’s safe to say that I didn’t think Nowhere to Hide was anything like a John Woo movie, however despite not delivering on the sleeves promises, it left an impression that set me on the path to being a lifelong fan of Korea’s output. Regardless of the misguided expectations, even at the time I knew the opening 8 minutes were something special, and it’s an opening which I still class as one of the greatest even to this day.

While the initial scene gets plenty of attention, which has Ahn Sung-ki (who doesn’t have a single line) assassinating Song Young-chan on a rain soaked set of stairs, set to the Bee Gees ‘Holiday’ (and even inspired a Giordano commercial starring Jeon Ji-hyun), it only gets better from there. As the credits appear onscreen we follow Park Joong-hoon’s dungaree adorned cop, sporting possibly the most distinctive swagger ever put on film, as he gate crashes a gangsters beat-down, all set to punk band Cherry Filter’s rendition of the trot song ‘Hae Ddeul Nal’. Joined by then new face on the block Jang Dong-gun, what follows is a monochrome assault on the senses of flashy editing techniques and electrifying sound design, incorporating slow-motion, jump cuts, step-printing, still frames, and just about anything else you can name. Anyone who watches the opening to Nowhere to Hide, isn’t likely to ever forget it.

Hearing the distinctive Korean tone and intonation for the first time also set it apart from anything I’d watched previously, and combined with the unique aesthetic, there was something unmistakably alluring about this newfound world of cinema. However finding other titles to explore Korea’s output wasn’t so easy back at the start of the millennium, with 2003 being the year that really opened up the floodgates for much of Korea’s output (thanks to the likes of Park Chan-wook’s OldBoy, Kim Jee-woon’s A Tale of Two Sisters, and Bong Joon-ho’s Memories of Murder). Even Shiri, another movie from 1999 that was largely credited as Korea’s international breakthrough, didn’t get a release in the UK until 2003, also by Tartan Video.

So for close to 2 years, while there seemed to be an unlimited number of Hong Kong and Japanese movies to watch, I found myself barely watching more than a handful of other Korean productions. Thankfully 15 years on it’s very much a different story, with the Korean Film Archive actively releasing plenty of material from the pre-1999 era (indeed for anyone that got into Korean cinema in the early 00’s, you could be mistaken for thinking the industry didn’t exist before 1999), giving the countries rich cinematic history the exposure it deserves.

It took around 10 years for me to watch Nowhere to Hide again, then fully aware of who the actors are. Little did I know in 2001 that both Park Joong-hoon and Ahn Sung-ki had already made a couple of movies together – Chilsu and Mansu from 1988, and Two Cops from 1993. After Nowhere to Hide they’d go onto to feature in 2006’s Radio Star, and Sung-ki had a cameo appearance in Joong-hoon’s 2013 directorial debut Top Star. It made me enjoy Nowhere to Hide even more, and appreciate many of director Lee Myung-se’s visual perks that perhaps I didn’t fully absorb at the time, because I was constantly waiting for some double handgun action to explode off the screen. I think Nowhere to Hide is probably the first usage of CGI blood in an Asian production, and the end fight in the rain soaked abandoned coal field remains one of the most visually striking finales put on film.

For the Korean Film Festival in Australia in 2014, Park Joong-hoon was flown in as the special guest, there to introduce Top Star. I still remember seeing him in a bar during a rare quiet moment, and every instinct in my body wanted to ask him for a photo, the plan being to recreate the iconic scene in which he and Ahn Sung-ki punch each other in the face at the same time (yes, I was going to be audacious enough to be Ahn Sung-ki). However nerves got the best of me, and I never went through with it, not even a standard lame selfie. Still one of my life’s regrets.

While both Ahn Sung-ki and Park Joong-hoon remain active in the Korean film industry, with close to a century of work between them, director Myung-se unfortunately hasn’t been as lucky. While he gave his unique visual style to both The Duelist in 2005 (which also featured Ahn Sung-ki) and M in 2007, what was set to be a spy caper set for a 2013 release titled Mister K found him at loggerheads with the production company, at a time when they were already in the midst of filming in Thailand. Stating irreconcilable differences, Myung-se left the production, leaving the studio scrambling for a replacement director, which eventually came in the form of frequent assistant director Lee Seung-joon. Mister K was eventually released as The Spy, and was met with almost universal disdain. Myung-se hasn’t worked since the incident, marking a real loss to the industry.

Regardless of all that’s happened since its release, I’m sure there are other fans of Korean cinema out there whose love affair with the industry started with Nowhere to Hide. In the UK at least, it was the first legitimate Korean title to get distribution by a well-known label, and while Shiri tends to take all the glory for giving Korean cinema its international breakthrough, out of the 2 it’s Nowhere to Hide that I find more frequently going into the DVD player. It’s one of those titles which has yet to make it to Blu-ray, however when it does, you can count me in for a first day purchase.

Read First Experiences of Asian Cinema: Korea Edition Part II

Read First Experiences of Asian Cinema: Korea Edition Part III

Read First Experiences of Asian Cinema: Korea Edition Part IV

14 Comments