PM Entertainment is a much-loved film production company from the height of the straight-to-video era. They began with tiny-budget crime and exploitation films but eventually rivaled Hollywood in terms of action spectacle. Their calling cards would become flipping cars, explosions and excessive violence on a large scale. They strived to outdo their DTV competitors by attempting the most daring action and stunt-work in American cinema.

But apart from action, one thing that isnt quite as discussed or explored about PM Entertainment is aesthetic. Before budgets became much bigger in the mid-nineties and they could afford to fill half a film with massive escalating car-chases, PM had a string of cheaper crime films with thick film noir atmosphere. PM also had a unique twist on noir, in that they combined it with martial arts and thus arguably created their own new genre of “Kickboxing Noir”.

But apart from action, one thing that isnt quite as discussed or explored about PM Entertainment is aesthetic. Before budgets became much bigger in the mid-nineties and they could afford to fill half a film with massive escalating car-chases, PM had a string of cheaper crime films with thick film noir atmosphere. PM also had a unique twist on noir, in that they combined it with martial arts and thus arguably created their own new genre of “Kickboxing Noir”.

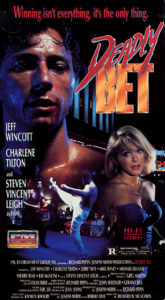

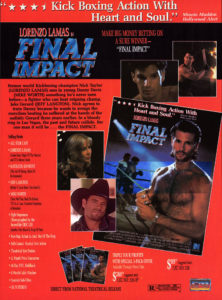

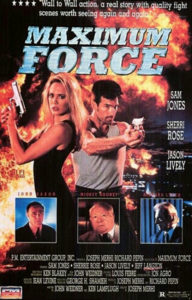

These pictures include Deadly Bet (1992) and Final Impact (1992), both filmed in neon-lit and seedy Las Vegas locations. This cycle of films culminated in the pinnacle of kickboxing-noir pictures: Maximum Force. The first two films were shot by Richard Peppin (Peppin being the “P” in PM Entertainment) but Maximum Force would be shot be cinematographer Ken Blakey and directed by Joseph Merhi (The “M” in PM), where they would take the “Kickboxing noir” style to a new aesthetic extreme.

Ken Blakey

Cinematographer Ken Blakey recalls: “The classic film noir from the 40’s and 50’s is always basically a crime story. Film Noir is not funny, nor is there really romance. There may be passion between characters leading to love, but it is usually unrequited or interrupted. There is a protagonist (fighter, cop, everyman) and an antagonist (gangster, rich man, another fighter, or cop), and a woman. Generally the “good” fighter loses the girl who comes under the power of the “bad” fighter (good and bad referring to character traits with which the audience can identify). The hero must defeat the villain usually by conquering him either physically, violently, or by subterfuge, winning a contest or any/all of the aforementioned”

These narrative elements couldn’t be more true than with Deadly Bet, where Jeff Wincott literally offers his wife as collateral when gambling on a kickboxing match, which he ends up losing. Charlene Tilton literally becomes a possession of villain Steven Vincent Leigh until Wincott can get things together and fight in the ring to win her back.

Such a politically incorrect plot couldn’t exist today in the #metoo era, but its also unlikely to have existed in mainstream Hollywood at the time either. It’s a good example of the kind of risk taking and edginess that can only be achieved in independent film, much like the envelope being pushed in the pre-code noir era. Apart from this, it has many of the hallmarks of the noir genre in terms of gangsters, nightclubs and a down-on-his-luck protagonist sucked back into the underworld.

PM even took this Las Vegas backdrop and fused it with an almost Karate Kid-style narrative with Final Impact (1992). In that picture, Lorenzo Lamas plays a jaded, hard-drinking former kickboxing champion fixated on training a protégé (Michael Worth) to enact revenge on a rival. At this point in time, PM was based in Las Vegas and many of their films inhabited similar casino-strip locations, which meant they could reuse locations, B-roll and make films quite efficiently.

Blakey remembers: “Rick Pepin used to say to me, “I want to see the money right up there on the screen”. Joseph Merhi could, I believe, actually get blood out of a stone, and I mean that with the greatest respect. Joseph knows how to wring out a dollar! Joseph and Rick brought in the best people for every department including the fight coordinators, stunt teams, and special effects. Most of those films from the early 90’s were shot on 15 day schedules so we all had to work fast and make it great. Rick and Joseph knew exactly what the straight to video and international markets (theatrical and video) wanted. There was a formula and the stories were plugged into that formula with over the top action, action, action.”

“I came to L.A. from San Francisco as a commercial photographer/cinematographer. I met Rick Pepin and he liked my showreel even though I had no feature film elements. I had a lot of experience in fashion, product, and corporate work so I could make anything look good. Rick was a good cinematographer, but he needed someone to light for him so that’s how I got my foot in the door just as they were making the transition from 16mm ultra low budget movies to 35mm films with known actors and bigger production values. The film noir look in the martial arts films in 1990/91 were shot by Rick with me as his Gaffer and 2nd camera. They liked the work and the shows did well so they gave me a shot as DP. I was assigned to a picture called A Time to Die with Traci Lords and Richard Roundtree. A police/crime story. I gave it a dramatic look, but I didn’t want to push it on my first outing so I stuck with a more polished commercial look. It turned out well and so next up was Maximum Force,” adds Blakey.

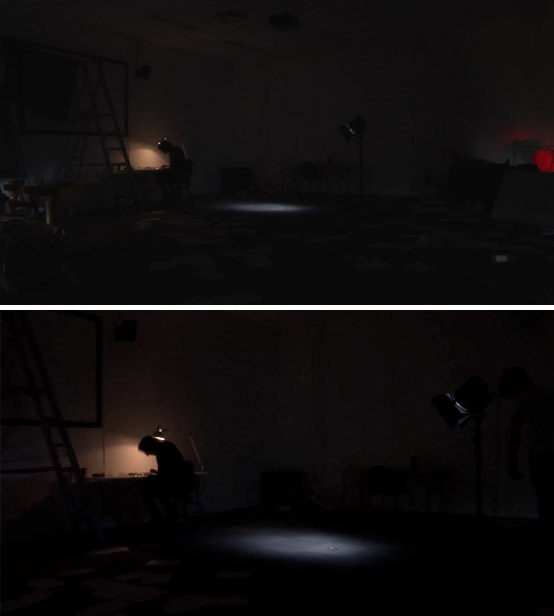

Maximum Force was a rather B-star-studded ensemble featuring Sam Jones (Flash Gordon), Jason Lively (Dukes of Hazard), Sherrie Rose (King of the Kickboxers), and John Saxon (Enter the Dragon). They are a dream-team of cops united together to take on crime boss Richard Lynch (Invasion USA) and his network, which includes corrupt politician played by Mickey Rooney! The film exists almost exclusively at nighttime or inside a mysteriously-lit wearhouse, where most of the second act takes place. This wearhouse would be a space for martial arts training, meditation, contemplation and interpersonal drama amongst the police. The atmosphere here was clouded with dust, smoke and stylistic lighting. One of the most audacious shots in the picture is a wide angle that slowly tracks-in on Sam Jones as he starts to skip with a jump-rope. The ginormous space is surreal, more akin to an art-film than a B-picture and the jump rope creates plumes of dust from the concrete floor that add to this atmosphere.

One of the most audacious shots in Maximum Force.

Martial arts is a less prominent theme, but when it punctuates the film its usually backlit and stylised. A couple of these kickboxing sequences take place on a nightclub stage amongst cigar-smoke and highlighted by theatrical lighting. Another fight scene atop a skyscraper takes place with a background of moonlit industrial exhaust fumes, appearing like white fire, contrasting the physical movement of kickboxing silhouettes.

“The noir aesthetic in Maximum Force was strictly my choice. Of course, I had to give the studio a commercially viable product that they could market, but when dailies started coming in they loved it. At the time I remember seeing two pictures shot by cinematographer Bojan Bazelli. They were King of New York (1990) and Deep Cover (1992). They both had a very dark look and used saturated colors in the lighting. Maximum Force was my third show as Director of Photography for PM and I decided to just let it all hang out. What makes it Film Noir is the lighting and camera. Extreme angles, wide lenses, and most of all DARK. Even in daylight the contrast between sun and shadow is often emphasized. At night faces are back or side lit with little or no fill light. The “unseen” adds to the drama and sense of foreboding,” says Blakey.

“On this one I went all the way since most of the story takes place at night in the dark underbelly of the city. I used large source light to ¾ backlight much of the action and the characters themselves. In addition I triple corrected one side to the blue spectrum and on the other side triple corrected toward the yellow. It was a success and I probably get more comments on Maximum Force than any other film. I was just chasing an aesthetic that I had fallen in love with in my early career and had the opportunity to realize it. I brought in lots of smoke and “radical” lighting and PM loved it,” Blakey adds.

Blakey continues: “I don’t recall specifically thinking of Maximum Force as a martial arts picture at the time although it certainly falls well into that category. I saw it as a crime drama with action. During those years martial arts were the default method of physical engagement in movies just like fist fights had been in westerns and mysteries. Those black and white mystery/crime stories of the 1940’s and 50’s were the first things that attracted me to film making and it was really the shadowy lighting that tickled my aesthetic sense. I don’t think I ever really thought about “marrying” martial arts with noir. It just seemed like a natural fit. Funny story … when the film was sold in the German market QC (Quality Control) for television broadcast drained most of the color out of those night scenes. When I heard about it I was apoplectic, but what can you do. I think the DVDs currently available in the U.S.A. market look very good. On my next picture with PM, Intent to Kill (1992), I went really dark as well, but with a different flavor.”

At the same time as these pictures, John Woo was producing crime films in Hong Kong, which made a departure from martial arts, instead choosing gunfire as the means to be balletic. They had elements of noir and French gangster pictures like Le Samurai but took their action from the gory Westerns of Sam Peckinpah. Hollywood took note of these startling Woo pictures and imported the director to America, while PM attempted their own heroic bloodshed pictures with such titles as The Sweeper (1996) that amped-up spectacle. Unlike Hong Kong, which had incredible restrictions and regulations on what film crews could achieve on the roads, PM had much more freedom on the streets of Las Angeles to create real havoc.

Ken Blakey explains: “I think a big influence at that time was John Woo’s Hard Boiled (1992). He took action to a whole new level in that show using wires, ratchets, and gunfire at a level not seen before. Again, no CGI, and it totally sells today. I still have my Laser Disc! Another influence for me was Steven Seagal’s Out for Justice (1991) both cinematically and the martial arts.”

“The Sweeper represented another step up in the action genre for us at PM. The opening car chase on the pier, the night freeway extravaganza, and then the day freeway chase where C. Thomas Howell climbs onto the wheel of an in flight airplane out of a moving convertible and the subsequent “air” fight and fall of the villain is still amazing. For those Freeway chases, with all the rollovers, crashes, explosions, etc. we were using 9 cameras at any given time. Four or five operated cameras shooting from “camera cars”, or from inside the vehicle, or telephoto shots to stack up the action and in addition four or five Eyemo’s which are small 35mm cameras housed in “indestructible” steel boxes that are placed and disguised on the road where they can be hit by a flying car, explosion, etc. That’s how we get those shots where the exploding car lands on the camera. When that happens I call those the “Bingo!” shots. No crew members or actors were harmed in the making of The Sweeper. And let’s not leave out fantastic stunts, driving, special effects (explosions, etc.) and great editing! Remember, there was NO CGI … It was all real.”

The Sweeper’s “nighttime freeway extravaganza” is a sequence where a dozen falling gas bottles from a truck are shot by a machine gun to explode at certain moments along the road during a conflict between two different speeding vehicles. The pitch-black sky is the perfect backdrop to highlight a series of jaw-dropping explosions and fiery car-flips. In this dark atmosphere, the mixture of glowing yellow headlights zooming past, red break-lights reflecting on the wet bitumen, explosions peppered along the highway and cars flipping and rotating in the night sky evokes a similar light and movement to Van Gogh’s painting “Starry Night”.

The original noir pictures of the 1930s were shot outside mainstream Hollywood in a place or status referred to as “Poverty row”, a series of basic studios that churned out “B” pictures to play after main features. But occasionally these films were innovative and ended up influencing Hollywood itself. In the early nineties, PM would parallel this history as they too used noir-style lighting techniques to create atmosphere and aesthetic on a budget for the DTV market.

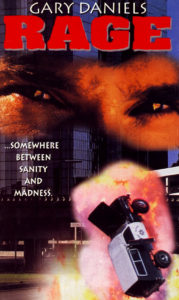

But as film critic Paul Bramhall points out about Rage (1995), which was also shot by Ken Blakey, PM would overtly challenge Hollywood and possibly influence it in the process: “Echoes of much of the stunt work on display in Rage, can be seen in some of the most popular mainstream action movies of the last 20 years.. The climax of the chase scene of Rage is more than a little reminiscent of the climax to the epic car chase from The Matrix Reloaded … Another scene has Daniels dangling off a building with the rope of a window washing outrigger, which he uses to run across the buildings side to create enough momentum to launch himself towards a….well, I won’t spoil it for anyone who’s yet to see it. But the same concept would be used 16 years later when Tom Cruise would scale the Burj Khalifa in Mission Impossible: Ghost Protocol.”

Ken Blakey continues: “Selling the punches/hits, continuity of the fight, and editing. Camera angles must be set in such a way as to give the illusion of connection. Stunt people don’t actually hit each other during a fight so the camera must be set at such an angle as to suggest connection and edited with the next shot to carry through on that connection while maintaining continuity of the movement of the players to suggest a real sequence of events. More than one camera is generally used to capture each sequence to give the editor more flexibility to speed up the action and give it impact.”

Scene from Nicholas Ingerson’s student film “Elevator” (2018)

The history of PM Entertainment is not something just kept alive by those reminiscing a bygone video-rental era. Recently a twenty-one year-old student at Australia’s most prestigious film school (VCA) asked me “Have you seen The Sweeper?” He went on to detail his admiration for the “night freeway extravaganza” and other spectacles. But the student also told me that when he made one of his short-films last year, a sci fi reminiscent of Shane Carruth’s Primer, that he made his cinematographer watch Maximum Force, particularly those surrealist scenes in the atmospheric wearhouse. So apart from overt Hollywood tributes to their action sequences, there is also evidence that PM has an aesthetic legacy that continues to be influential to this day.

Superb artice Micheal, enjoyed this one a lot, very informative too.

Thanks DC!

Great piece! Love hearing the comments from Blakey, who is an excellent DP and contributed so much to the success of PM’s product..

Thanks William .. Yes, Ken Blakey lensed some of the great genre pictures of that era. And I thought he should get a bit more credit for this work, particularly with Maximum Force.

I really enjoyed Final Impact.

Especially the training scenes where Lorenzo Lamas teaches techniques and tactics. I didn’t know Lamas was such a proficient martial artist!

Yeah, those scenes may not break blocks of ice or involve rope-pullies to make Michael Worth do the splits, but they really do develop the characters and master/teacher relationship … Plus have a few good pointers about unpredictability.

PM was a great company even if I didn’t love all of their films. Maximum Force was really cool, and I couldn’t believe how convincing Sam Jones was out of character.

I wish they were still around today. I’m sure they would have advanced with the times while keeping their core principals.

i’m sorry that is a dumb comment,…… “advanced” with times ….. yeah right , thats a cynical way to phrase it …how exactly has moviemaking “advanced” from the days of PM its been going downhill fast, have you seen PMs succesor / todays equivalent ASYLUM company ? those flicks are horrendous

so there would be no point in having PM around , they would put out lifeless generic product as most b companies do nowadays , like you figured yourself, they wouldn’t be still doing those handmade effects, and those flicks were INSANITY, unfortunately unlike CANNON films a decade before they seem to be not as well known what everbody who knows those movies says is really a shame

There’s no need to be rude. Nothing in my comment was cynical. Asylum is nothing like PM, and it can be argued that PM would be making movies like Close Range or Valentine these days.

gotta say interesting article but on factual error .

you say HK movies were more regulated / restricted than hollywood, quite the opposite is true (ever seen a jackie chan flick + the stuntwork ????) , HK movies were pretty hi octane crazyness, they were known for their over the top style and it was always said it was because there was NO rules ….. i mean its pretty common knowledge that the western world (usa europe) has the hightest set of regulations by far in the world

Different sorts of regulations. In Hong Kong, it was very hard to obtain freedom to drive over the speed limit anywhere for a chase scene, hence why so many car chases were under-cranked and looked like Keystone Cops. In other aspects, Hong Kong was less regulated for sure, but unfortunately they rarely had car chases that competed with the heights of American cinema. Some of the best car chases in Hong Kong movies were in-fact shot overseas, like the one in Armour Of God.