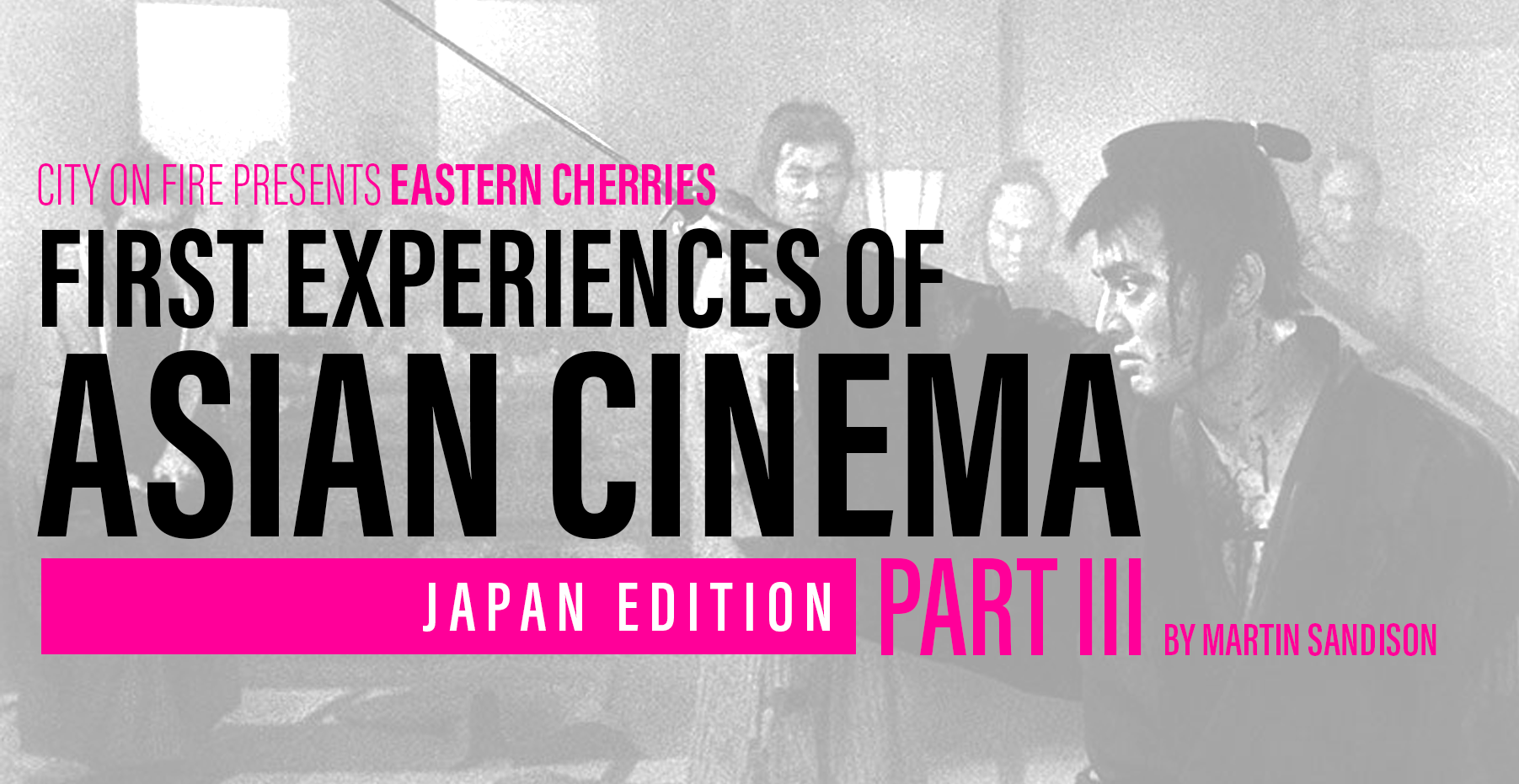

Until 2008 my interest in Japanese movies had been centred around Kurosawa, and some Anime. I loved Yojimbo, Seven Samurai and Akira, but for some reason I had not burrowed deeper in to the treasure trove of Japanese film. When my local cinema in Edinburgh, Scotland screened a Japanese cult film season, here was my chance. The season was programmed by Matt Palmer, director of recent Netflix original Calibre, my favourite Scottish film in many years. There were 11 movies on in the season, with films such as my favourite horror of all time, Nobuhiko Obayashi’s House, Seijun Suzuki’s psychedelic odyssey Branded to Kill and Kinji Fukasaku’s docu-style Yakuza Graveyard. It was the first one screened that would blow my mind sky high, Kihachi Okamoto’s Sword Of Doom.

I went in to the screening knowing nothing about film, director or star; I didn’t even realise when watching the film that star Tatsuya Nakadai had been the villain in Yojimbo. As the first few frames unfolded, I was rapt, and it was one of those cinema experiences that I will not only never forget, also one that changed my life. Here was pandoras box opening before my eyes; and the knowledge that this film would remain within my top 5. It still is, ten years later.

Within that first scene Okamoto presents Nakadai’s Ryunosuke as cinema’s ultimate anti-hero, as he kills an old man and leaves the mans granddaughter to mourn, his pleasure in killing so evident. Ryunosuke may be nihilistic, but the film is no exercise in nihilism; as an exploration of violence and psychopathology it is near unmatched, and was a complete break from the earlier Samurai films that focused on honour and the code of Bushido, presenting the Samurai as superhuman. While the film does not plumb the depths of Ryunosuke’s psyche, the portrait is one of a man who lives with his demons close at his side and is obviously a psycopath. One that is fucking fantastic to watch.

The film follows Ryunosuke as he is revealed to be the son of a Master of a swordplay school, who has disgraced the school due to his evil ways. He leaves the school after meeting a young woman Hama (Michiyo Aratama) who he has a child with, and falls in with the Shinsengumi, a a gang run by the Tokugawa shogunate who carry out crimes and assassinations. By chance he accepts a duel when passing a school, only for the student he challenged to go after Ryunosuke as his brother is the man Ryunosuke killed in an earlier match. These disparate narrative threads weave in and out, with the attention on Ryunosuke and his escalating insanity.

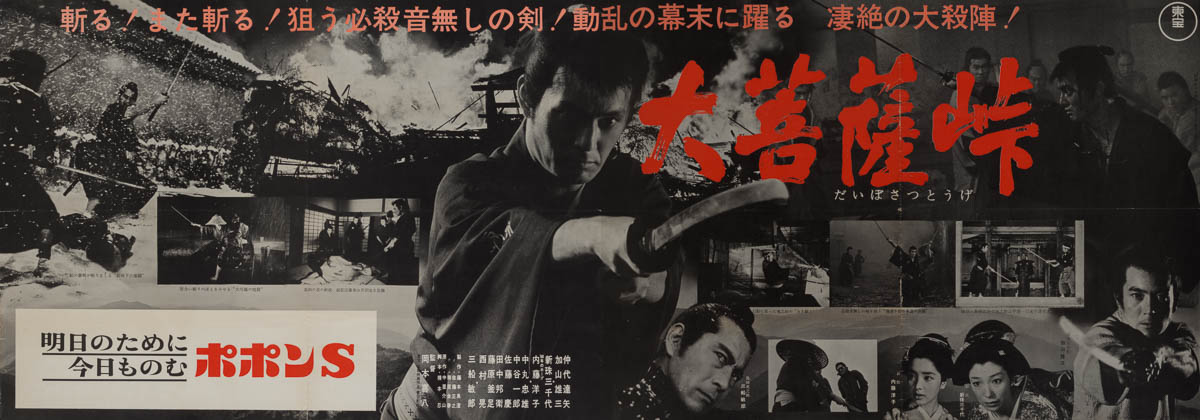

The genesis of Sword of Doom is interesting. The film is based on a serialised novel Daibosatsu toge, by acclaimed novelist Kaizan Nakazato, who died before the serial was completed, in 1944. There have been versions of this story by such film makers as Hiroshi Inagaki (Samurai Trilogy) in 1935, Tomu Ichida (Bloody Spear at Mount Fuji) in 1957, and the master Kenji Misumi (Lone Wolf and Cub: Sword of Vengeance) in 1960. This is a story ingrained in the wartime and post-war Japanese collective psyche, one that is originally Buddhist in intention, with the Karma of it’s characters, especially Ryunosuke, expressed throughout the narrative. The screenwriter Shinobu Hashimoto was responsible for the scripts for Kurosawa’s classics Rashomon and Seven Samurai, and here his approach to the storyline is very different. It would be interesting to know how much Okamoto diverged from the script, as there are such huge jumps forward wherein the view must fill in the blanks. Hashimoto was an authority on Japanese history, and there are some real historical characters in the movie, such as Toshiro Mifune’s master swordsman Toranosuke Shimada, while Nakadai’s character is a complete work of fiction. The way Okamoto condenses the wealth of storylines in to a single film is a point of contention for those who have watched the film.

The narrative is fractured and fragmentary; huge jumps in time frames occur, storylines are not resolved and characters come and go. This is partly due to the fact that, like the earlier adaptations of the novel, the film was supposed to the be the first in a trilogy. Another factor that the films champions, such as myself, say is that Okamoto frames the film from Ryunosuke’s subjective view; in terms of film making and narrative. As Ryunosuke slides further and further in to pychosis both aspects reflect this, with the fragmented shards of the story indicative of his muddled and tortured mindset. In the aesthetic aspects some of the most darkly beautiful use of black and white widescreen composition, and impressionistic, complex lighting arrangements combine to create a vision of Ryunosuke’s inner hell.

What use would all of these aspects be without a visual representation of the violent poetry of Ryunosuke’s form as a swordsman? Okamoto presents this in a way which blows my mind, and every time I watch the film the fights become more and more fully formed, in a way that is matchless in Samurai cinema. In fact the film was not successful in Japan (due to factors such as the fact there were already films made about the subject and the strangeness of the storyline), but in the West it was embraced, and became an almost cult classic. This is in no small part due to the swordplay scenes. There are three major battles in the film, and each has their own unique stylistic tics and aesthetic approach.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XgVbsoY_4_k

The first is the most iconic. Ryunosuke has just killed an opponent in a formal match, and the man’s clansmen are setting an ambush for him. He descends a path lined with trees, backlighting creating beautiful patterns of mist. As the men approach and the action begins, it is all shot in a long moving take, with Ryunosuke’s flowing style and unmatched form dispatching each man with a ruthless brilliance. When I first saw this on the big screen my eyes widened in awe, just the same as when I watched Enter the Dragon‘s fight scene with Lee vs Han’s guards. As he walks away, the films most iconic shot, and my favourite in film history, is revealed: the victims of his devils sword in the foreground and Ryunosuke in the background, mist surrounding them. I recently bought a T-shirt with that image on it, and keep getting compliments.

![]()

The second features that legend of Japanese cinema, Toshiro Mifune, battling men Ryunosuke is in league with. Mifune’s appearance is a glorified cameo really, and the hoped for battle between the two that would be a rematch from previous films, does not emerge; but again this scene is iconic, wonderfully staged and reveals much about the protagonist. Set in a pathway in a blizzard of snow, Mifune emerges from a palanquin cutting a swath through his enemies with Okamoto using a much more dynamic shooting and editing style, favouring close in angles and quick cuts. Ryunosuke stands and is rendered impotent by Mifune’s way with a sword, and this marks the time he becomes not just a psychopath, but psychotic.

Come the end of the film Ryunosuke’s descent in to madness has taken hold completely, and he begins to see the Ghosts of his previous victims, attempting to use his sword to drive them away. The film making here is some of the most atmospheric and surreal in all cinema, as he slashes endless corridors of curtains, the ghosts appearing in silhouette. A gang comes in to kill him, and one of the greatest swordfights of all time plays out, with techniques light years ahead of their time utilised, and a heightened sense of violence and gore that is extreme for the time the film was released. One sequence of rapid fire cuts with close ups of maiming and slashing predates Lone Wolf and Cub by 6 years, and longer takes with again a moving camera are magnificently realised.

The feeling of adrenalin as I left the cinema, and a world previously untapped and waiting for exploration was so strong, almost the same as when I watched my favourite film Hard Boiled at age 15. Every aspect of Sword of Doom is is dynamite, but I was haunted by star Tatsuya Nakadai’s performance. In every scene he makes Ryunosuke so hard to read, but those intense eyes burn with a fire that looks beyond the moment. His charisma combined with this makes his depiction my favourite performance in all cinema, and Nakadai has since become my second favourite actor, after Chow Yun Fat. Like Chow, his filmography is so dense its hard to see everything, but Sword of Doom led me to more Okamoto films he starred in like the comic Samurai film Kill!, and one of Nakadai’s last screen performances and Okamoto’s last film before he died, Vengeance for Sale. From there I discovered Masaki Kobayashi’s masterful Hara Kiri and Kwaidan, both starring Nakadai.

Sometimes you don’t know when a film is gonna creep up and bite you in the ass. Sword of Doom did just that to me, and the pain made me open my eyes to the endless possibilities of Japanese cinema. As I write these words I’m thinking about the film I will finish watching next, Hiroshi Teshigahara’s Woman of the Dunes. Having watched half, it is already a masterpiece to me, and having read the book, I know it will just get better. Made in 1964, two years before Sword of Doom, these two are just a couple of examples of the goldmine that stretched on in to the late 70’s. To me, it is doubtful any of the films I have left to watch will match the undying dark beauty at play in Sword of Doom.

Read Eastern Cherries – First Experiences of Asian Cinema: Japan Edition Part I

Read Eastern Cherries – First Experiences of Asian Cinema: Japan Edition Part II

Read Eastern Cherries – First Experiences of Asian Cinema: Japan Edition Part IV

Man, I really need to see more chanbara flicks, and ‘Sword of Doom’ sounds like a great place to start. It’s a genre I haven’t really explored, with the exception of the well known Kurosawa classics (the only Zatoichi movie I’ve seen is the Kitano version – shameful I know), and I know there’s a heap of good stuff out there. ‘Sleepy Eyes of Death’ is another series I regularly hear good things about. Great piece Martin, and the mention of a film festival ensured it had that distinct ‘Sandison’ feel. 😛

Thanks Paul! I have watched a few of the Sleepy Eyes Of Death series, yeah great stuff, but nothing I’ve seen comes close to Sword Of Doom.