After going through a golden age in the 1960’s, Korean cinema went through one of its most challenging decades in the 70’s. Economic growth saw television sets make their way into most households and become the medium of choice, while the ushering in of the Yushin era saw president Park Chung-hee tighten his dictatorial grip on the country, imposing strict censorship on any creative work. After a decade that produced a number of classics, many filmmakers saw themselves stuck between a rock and a hard place within a remarkably short timeframe. Budgets were no longer there, and even the slightest sign of criticism towards the government or sympathising with communism became a crime punishable by prison (and indeed, many directors did end up behind bars).

Park Chung-hee

The cinematic landscape would stay that way for most of the next 20 years, before it began its next renaissance in the 1990’s, by the end of which Korean productions had even broken through onto the world stage. As challenging a time as it was when it came to freedom around artistic expression, it was arguably due to such circumstances that the Korean taekwon-action genre was born. Korea was far from an untapped resource in terms of its martial arts talent in the early 70’s, with Bruce Lee having already enlisted hapkido practitioners Hwang In-shik and Ji Han-jae to feature as opponents in his Hong Kong productions, Way of the Dragon and Game of Death (although audiences wouldn’t get to see Han-jae in action until its eventual release in 1978) respectively.

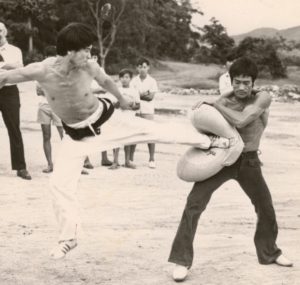

Hwang In-shik and Bruce Lee in a behind the scenes photo from Way of the Dragon.

While Hong Kong’s Shaw Brothers studio also had several Korean actors under contract who became regulars throughout the 70’s, such as James Nam and Kim Ki-joo, it was rival studio Golden Harvest that took a more aggressive approach to pushing Korean talent to the fore. With the untimely passing of Bruce Lee, who was signed to the studio at the time, owner Raymond Chow became eager to find a new star and appeared to believe Korea was the best place to look. However without the formal Peking Opera background or studio backed martial arts training that most performers in Hong Kong came with, meaning that its stars were usually proficient in both acting and action, instead Chow chose to solely focus on physical talent.

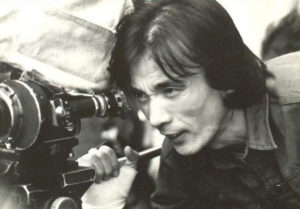

This approach only resulted in a rotating door of one-time Korean leading men who were all proficient with their feet, but less so in terms of onscreen charisma and acting talent. In 1973 we got Jhoon Rhee in When Taekwondo Strikes, in 1975 it was Byong Yu in The Association, and in 1976 it was the turn of Park Jong-kuk in Tiger of Northland. In Korea itself, the emergence of the taekwon-action genre wasn’t so much about needing to replace a star of Bruce Lee’s stature, so much as it was finding an avenue to make movies that was cost-friendly and didn’t risk offending the authorities. To that end it was Lee Doo-yong who became the pioneer, a director who debuted in 1970 helming dramas, but who’d soon come to find his place as an action movie director.

While ‘dachimawa’ movies, roughly translated as tough guy flicks (and were successfully spoofed in director Ryoo Seung-wan’s 2008 feature Dachimawa Lee), were already a staple of Korean cinema, their action beats mainly consisted of guys in trench coats throwing haymaker punches at each other. Doo-yong wanted to elevate the genre, utilising the kicks of taekwondo to create a new kind of action aesthetic, and he’d go on a large-scale audition process in 1973 to find a leading man who was the complete package. With the benefit of hindsight, based on Golden Harvest’s experience it’s perhaps not a surprise that he didn’t find anyone domestically who fit the bill, and would ultimately be introduced to a Korean living in the U.S. who ticked all the boxes, a man by the name of Han Yong-cheol.

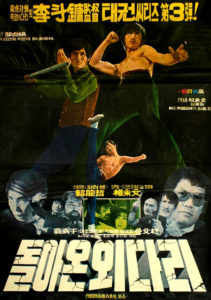

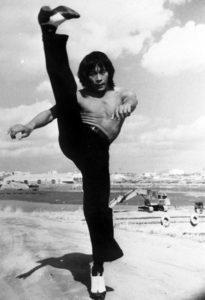

Although Yong-cheol was only 20 by the time cameras started rolling in 1974, it was easy to see why he fit the bill with his tall frame, youthful good looks, and ability to throw a mean kick (or 10). In much the same way that the likes of The Chinese Boxer and King Boxer saw a transition from swordplay-based productions to empty handed combat in Hong Kong, so Lee Doo-yong and Han Yong-cheol’s collaborations did the same in Korea. Together they’d crank out 6 movies in 1974 – Returned Single-Legged Man and its sequel, Left Foot of Wrath, Bridge of Death, The Manchurian Tiger and A Betrayer – and while Yong-cheol is playing a different character in each one, it’s just as easy to imagine all take place within the same cinematic universe.

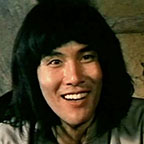

Han Yong-cheol in The Great Urgency Network.

In part this is down to Doo-yong’s decision to set his narratives in 1930’s Manchuria, a time when China, Japan, and Korea were all vying for control of the region. The term ‘Manchuria western’ had already been coined at this point, a result of Korea being inspired by the Italian spaghetti westerns, which local filmmakers saw as proof that it wasn’t only Hollywood the western genre solely belonged to. However while the majority of Manchuria westerns relied on gun slinging or sword clanging for their action, it was Doo-yong and Yong-cheol who effectively replaced guns and swords with kicks. Maintaining the same aesthetic in terms of wardrobe and setting, under the choreography of Kwan Yung-moon the action was adapted so that it was a flurry of footwork that broke out, rather than the bullets or blades that audiences had become accustomed to.

Placing the taekwon-action tropes within the context of the Manchuria western also saw each production essentially stick to the same template when it came to the plot – since the Japanese army had a strong presence in Manchuria during this time, the stories almost always involved independence fighters who were struggling for the freedom of the Korean people. Far removed from the narratives based in the present day, the simplistic storylines and patriotic values that underpinned them guaranteed they’d pass the government censorship boards unscathed. While it may have made many of Doo-yong and Yong-cheol’s collaborations largely interchangeable, what they lacked in individual identity they more than made up for in the visceral nature of their action scenes, and Yong-cheol became an instant hit with local audiences.

While Doo-yong may have found the leading man qualities that he was looking for with Yong-cheol, thankfully he had the foresight to not send away the unsuccessful applicants empty handed. More than 30 taekwondo practitioners who auditioned would be cast in supporting roles, basically giving Doo-yong the instant Korean equivalent of what Hong Kong cinema had readily available through its stuntman community. Watching the likes of Returned Single-Legged Man it’s possible to get a glimpse into the beginnings of soon-to-be genre regulars like Hwang Jang Lee, Kwon Il-soo, and Elton Chong playing villainous lackeys, destined to be on the receiving end of Yong-cheol’s fearsome kicks in various scenes.

It was also in 1974 that the Motion Picture Promotion Corporation (now called KOFIC) established a strategy to encourage the sale of taekwon-action productions to overseas markets. Could this be how so many of them ended up in the hands of Godfrey Ho and the Asso Asia gang? It’s very possible (at least the Doo-yong and Yong-cheol collaborations), and equally so that the Korean distributors could have no idea at the time of sale that the versions released in English speaking territories would be completely butchered, even so far as replacing the names of the cast and crew! Locally the strategy meant that studios were keen to replicate the success of Yong-cheol’s arrival in Korea, and they once more turned to the U.S., hoping to find someone who could continue the momentum created around taekwon-action.

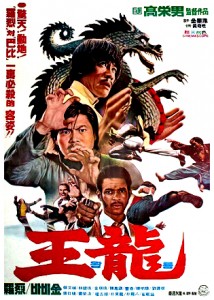

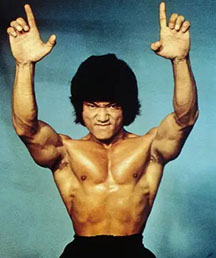

Bobby Kim in Mark of the Black Dragon.

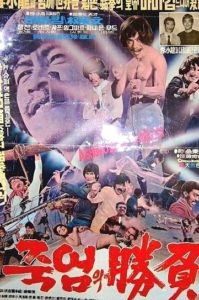

It would be the Taechang Heung film company who struck lucky first, when a screenwriter by the name of Kim Hak-gyung took the initiative to introduce his brother, who’d been operating a taekwondo school in Washington DC and even trained the U.S. Air Force. Going by the name of Bobby Kim, his slightly grizzled older appearance and Charles Bronson-esque features made him an instantly attractive proposition, and straight off the bat he was offered a 10-movie deal (although ultimately he’d only sign up for 5). The marketing machine wasted no time hyping up their newly found leading man, proclaiming that “a U.S. film company tried to present him as Bruce Lee’s successor. But he returned to Korea as he wished to star in taekwondo films.” The poster for his 1975 debut Mortal Battle even featured a photo of Bobby Kim standing alongside Bruce Lee!

To differentiate himself from Yong-cheol, Kim’s trademarks became his moustache and leather jackets, offering a more rugged and masculine demeanour when compared to his counterpart’s youthfulness (Kim was 34 when making his debut compared to the barely out of his teens Yong-cheol). Although thematically the vehicles he starred in didn’t stray too far from what was already working well, the productions Kim starred in went a slightly different route by being based in more a more contemporary setting. What didn’t change was that he was always out to deliver a beating to either evil Japanese attempting to claim Korea as their own, or (to shake things up a bit), Chinese communists. Kim became a regular throughout the 70’s in titles like A Viper, Invitation from Hell, and Only Son for Four Generations, making him a firm fixture on Korean screens.

While Yong-cheol would continue to work on productions aimed purely at the domestic Korean audience during his time in the film industry, Kim did spread his wings a little further by featuring in the rarely seen Indonesian production Tengkorak Hitam in 1978. He was also approached by Cheng Chang-ho, a Korean director working for the Shaw Brothers studio who was responsible for helming the hugely popular King Boxer, with an offer to become a part of the Shaw stable of martial arts actors in Hong Kong. However Kim’s heart belonged to his feet, and he’d turn it down citing a lack of interest in adapting to the kung-fu style of choreography, so in some ways perhaps the initial marketing around him wanting to stay in Korea to star in taekwondo movies could be true after all!

He would however collaborate twice with the star of Chang-ho’s King Boxer in the form of the Indonesia born Lo Lieh, both of which took place in 1976 (and while we can never know for sure, it’s possible to debate if it was Lieh who suggested to Kim he star in an Indonesian production). Lieh was already familiar to local audiences thanks to his iconic collaboration with Chang-ho, and would make the journey to Korea to co-star with Kim in The Deadly Kick and International Police. Notably Lieh would also co-direct with Go Yeong-nam, likely part of a strategy to make the movies they worked on together an attractive proposition to Hong Kong distributors, were he was a Shaw Brothers regular.

Much like Yeong-cheol, Kim remained active in the Korean film industry primarily in the 70’s before heading back stateside, with the difference being that Yong-cheol would retire from the film industry all together after 1981’s My Name is ‘Twin Legs’, while Kim would continue working in the U.S. Part of a wave of Korean talent that immigrated to America in the 80’s, director Park Woo-sang had helmed the 1977 Bobby Kim vehicles The Big Opponent and Noble Warrior, and the pair would collaborate several more times (see my ‘Hallyu in Hollywood’ feature for an in-depth look at them) on U.S. soil in the 90’s. While they never got to share the screen together, it’s undeniable that Han Yong-cheol and Bobby Kim represent the purest ideal of the taekwon-action leading man, with both leaving an indelible stamp on the genre.

It was during the same decade that the taekwon-action genre would prove to be a fruitful training ground for some of the silver screens most ferocious boot masters. Hwang Jang Lee may not have gotten the lead role during his audition, however he did leave enough of a lasting impression that he began to turn up as a lackey in almost every notable taekwon-action title of the era, frequently facing off against Han Yong-cheol and Bobby Kim. Ironically it was on the set of Lee Doo-yong’s 1975 production Disarmament, a title which starred neither and was intended to launch a new taekwon-action star by the name of Gang Dae-hui (it failed, he’d go on to star in Jailhouse the same year then disappear altogether), that visiting Hong Kong producer Ng See Yuen spotted Hwang Jang Lee.

Perhaps it was a blessing in disguise for Jang Lee that See Yuen visited on a production where he easily outshone the lead, but whatever the case their encounter led to the multi-talented producer, director, and writer inviting Jang Lee to Hong Kong. It’d have been interesting to see how Lee Doo-yong reacted to such news, since Hong Kong action cinema was still considered top of the food chain when it came to Asian action, so to see a supporting player receive an invite rather than one of their taekwon-action stars must have been jarring.

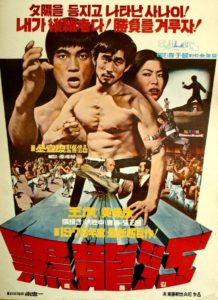

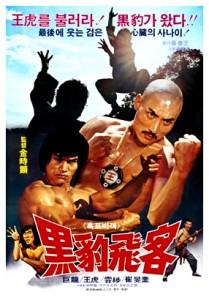

It was the Dong-a Export Co. film company that looked to strike while the iron is hot before Jang Lee would be whisked away off Korean shores. To rival the film companies whose taekwon-action flicks were being spearheaded by Han Yong-cheol and Bobby Kim, they decided to push a taekwondo expert who’d appeared in a couple of supporting roles to the fore. His name was Kim Wang-ho, who in the west would become popularly known as Casanova Wong, and rather than bank the entire success of a production on his shoulders (or should that be feet?) alone, director Kim Seon-gyeong was tasked with pairing him with Hwang Jang Lee as a co-star. The result was the 1976 double bill of Secret Agent and Black Dragon River, which with the benefit of hindsight offers audiences the rare opportunity to see the Silver Fox go toe to toe with the Human Tornado.

Within the same year See Yuen proved that his intention to work with Jang Lee was a serious one, but before making good on that invite to Hong Kong, he’d cast him as the villain for The Secret Rivals, a Hong Kong production under See Yuen’s Seasonal Films that shot in Korea (a subject which is worth another feature in itself!). If there was any doubt in his mind to if the effort to bring Jang Lee out of the country was going to be worth it, then his villainous turn as the Silver Fox who has to face off against John Liu and Don Wong Tao confidently put them to rest. The rest as they say, is history, and over the next 15 years Jang Lee would show up (almost always as the villain) in over 50 productions, becoming one of the most recognizable faces in kung-fu cinema.

The popularity of taekwon-action saw an increased presence of Korean taekwondo experts in many of the Hong Kong productions that shot in Korea around the mid-1970’s. It was in stark contrast to the likes of the Shaw Brothers production The Four Riders that shot there just a few years earlier in 1972, and featured an entirely non-Korean cast and crew. Like Hwang Jang Lee, both Casanova Wong and Kwan Yung-moon (who choreographed and featured in many of Han Yeong-cheol and director Lee Dong-yoo’s productions) benefitted from taekwondo coming into fashion in Hong Kong action cinema, with the pair clocking in memorable performances as a pair of high kicking guard monks in 1977’s Korea shot Hong Kong movie Shaolin Plot.

For Casanova Wong in particular it was like night and day seeing his kicks choreographed by someone like Sammo Hung versus his local output. While both Han Yong-cheol and Bobby Kim became bankable stars, as a leading man Wong never quite achieved the same popularity as his peers, and instead looked to forge a path starring in lower budgeted, more fantastical (or pulpier is likely a more appropriate term) outings. Frequently paired with directors Kim Jung-yong or Kim Seon-gyeong (no relation), Wong’s Korean output took taekwon-action out of its grounded beginnings, and looked to compensate for the often clunky choreography with the sheer outlandishness that was applied to it.

Productions like Four Iron Men and Golden Gate introduced a healthy dose of unintentionally amusing wirework, pectoral flexing bodybuilders covered in metallic paint, jangly earring wearing villains, and death via getting your head stuck inside a kimchi pot. While Wong would continue to be a taekwon-action mainstay throughout the late 70’s and early 80’s (even starring alongside Han Yong-cheol in My Name is ‘Twin Legs’), it was his incredible display of piston kicking in Shaolin Plot that placed him on the radar of the productions action choreographer Sammo Hung. Just as Ng See Yuen would invite Hwang Jang Lee to start appearing in Hong Kong productions, so Sammo Hung would feel the same way with Casanova Wong, initially casting him in a supporting role for his directorial debut The Iron Fisted Monk in 1977.

It would be the following year though when Sammo provided him with the leading role that immediately springs to mind when hearing the name Casanova Wong, which was ironically not in a taekwondo themed production, but rather as a wing chun student in Warriors Two. Despite the prevalence of wing chun’s ‘sticky hands’ technique, thankfully Sammo found plenty of opportunities to utilise Wong’s kicks in the narrative, including the famous over the table flying kick that effectively rounds off the finale against Fung Hak-On. What’s perhaps most interesting about Wong’s career though is not that he’s still making movies back in Korea even today (filming wrapped on Senior Bodyguard in 2022), but that his time working with Sammo Hung may have inadvertently contributed to the rise of another taekwon-action genre star.

When Bruce Lee passed away in 1973, he left behind an unfinished movie in the form of Game of Death, which during 1977 Golden Harvest decided to complete by filming new footage and creating a completely new plot. It was a Korean by the name of Kim Tae-jeong who was cast as one of the stand-ins for Bruce Lee when filming resumed, and with Sammo Hung onboard to choreograph the action, he didn’t waste the opportunity to have a pair of taekwondo practitioners face off against each other. The result was the famous greenhouse fight scene which pitted Tae-jeong and Casanova Wong’s kicks against each other (with plenty of flowerpot collateral damage along the way). Interestingly the fight is included in some cuts of Game of Death in certain territories, and turns up in the sequel Tower of Death in others, the latter of which gave Tae-jeong a starring role.

While the Bruceploitation genre was already around in 1977, Korea never had its own Bruceploitation star, but with news of a new Bruce Lee movie on the way featuring a plethora of Korean talent, it seemed this was the trigger for them to get in on the action. Although Tae-jeong’s brief time in the film industry saw him capitalise on his Game of Death casting with titles like Fist of Death and No Retreat, No Surrender, it was actually a complete newcomer who’d become Korea’s premier Bruceploitation star. Moon Kyung-seok was a bodybuilder who practiced both taekwondo and hapkido (the latter under Hwang In-shik no less), and thanks to having both the skills and a passing resemblance to the Little Dragon, found himself plucked from obscurity and given the screenname of Guh Ryong (which translates literally to Giant Dragon – see what they did there?).

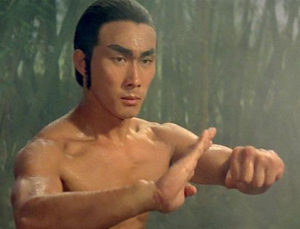

While Kyung-seok found himself labelled the Giant Dragon on Korean shores, in the western world he’d become known as Dragon Lee. With no supporting roles or prior experience onscreen, Dragon Lee burst onto the scene in 1977 in all his intense head shaking, high kicking glory by headlining The Last Fist of Fury. Lee represented a new type of taekwon-action icon, which saw the cool-headed steely gazes of Han Yong-cheol and Bobby Kim replaced by a high energy athleticism, with a typical Lee starring vehicle looking like he just downed a crate of energy drinks before the camera started rolling. Looking at Lee’s filmography it’s possible to see the impact that Hong Kong’s kung-fu trends had on its Korean neighbour, with his initial late 70’s productions being relatively straight-faced period pieces like The Five Disciples and Twelve Gates of Hell.

However in 1978 it wouldn’t be the completed version of Game of Death that ultimately had a lasting impact, but rather a little movie called Drunken Master, which starred a still relatively unknown Jackie Chan (despite filming many of his Lo Wei productions in Korea!). The impact of Drunken Master on the Korean peninsula can’t be overstated, with kung-fu comedy fever spreading like wildfire. This impact can be seen most blatantly through the filmography of Dragon Lee, who went from the aforementioned period pieces, to starring in manic comedies practically overnight. If Han Yong-cheol’s Manchuria westerns could be perceived as being an interchangeable set of stories that took place in the same universe, then the same could be said for much of Dragon Lee’s early 80’s output like Cheer, A Master and His Student, and Eighteen Martial Arts.

Usually decked out in a The Big Boss inspired wardrobe consisting of a white t-shirt and black slacks, the Dragon Lee brand in the 1980’s could best be described as Bruceploitation meets the kung-fu comedy, translated to the screen by way of taekwon-action. While such productions where a world away from how the genre had started less than 10 years earlier, what can’t be argued is that they were in touch with the times, and local audiences lapped them up. If Han Yong-cheol was the face of taekwon-action in the 70’s, then Dragon Lee was arguably the face of it in the 80’s, to the point that whenever the likes of Hwang Jang Lee and Casanova Wong returned to Korea, they’d usually be cast as villains for Lee to face off against.

The re-emergence of the kung-fu movie as a popular genre meant that we got to see the best of the taekwon-action stars face off against each other during this period. Dragon Lee would go toe to toe against Casanova Wong in 1981’s Secret Bandit of Black Leopard, and would further face off against Hwang Jang Lee in a trilogy of showdowns across Duel of In-ja Hall, Shaolin Yong-pal, and Nwoi Fighting Technique throughout 1982 and 1983. The transition that the taekwon-action genre was going through at the time is probably best represented by a production entitled Yong-ho’s Cousins. Having been absent from the film industry for 6 years, the original taekwon-action star Han Yong-cheol would make a fleeting return in 1981, headlining taekwon-action and dachimawa regular Lee Hyeok-su’s latest.

Like a passing of the torch, whereas in 1974’s Returned Single-Legged Man Hwang Jang Lee was just a small bit player who got to run away from Yong-cheol without throwing a single kick, 7 years later and the pair were now co-stars. Yong-cheol would only make one other movie during the same year and then retire from the film industry for good, however with the benefit of hindsight, we can be thankful he didn’t bow out before taking part in a knock down drag out brawl during the final reel with the Silver Fox himself. Indeed the 80’s itself would become an increasingly confusing era when it came to defining exactly when taekwon-action fell out of fashion. With that being said, if it’s possible to choose one title which could be interpreted as the last of the ‘pure’ taekwon-action movies, then it would likely be The Trouble-Solving Broker.

Also from 1981, it was a production which brought together the director responsible for creating the taekwon-action genre in the form of Lee Doo-yong, paired with Korea’s most recognizable action star of the era in the form of Hwang Jang Lee. Ironically it was Hwang Jang Lee who was cast as the villain to face off against Jackie Chan in Drunken Master, a continuation of working with Ng See Yuen whose Seasonal Films it was made under, and many Korean audiences at the time of its release had assumed Jang Lee was Chinese. Seemingly unaware he’d co-starred in a pair of local productions just a couple of years prior (blame the beard), after realising that the productions scene stealer was one of their own, it granted Jang Lee some leverage on his home soil.

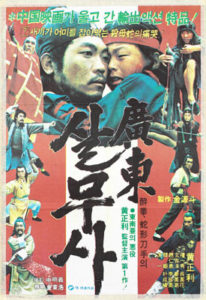

While he’d get to direct and star in the likes of Hitman in the Hand of Buddha and Kwangdong Viper, despite his formidable presence, Jang Lee’s star status in Korea never reached the same heights as the likes of Han Yong-cheol and Bobby Kim. It’s an easy argument to make though that this wasn’t so much about anything to do with his screen presence and skills, so much as it was about shifting audience tastes. Proof of Jang Lee’s lack of box office pull in his home country can be seen through Korea’s unique approach to co-productions at the time. While co-productions between Korea and Hong Kong had been around since the late 1950’s, in the 1980’s the collaboration Korea’s film industry had with its Hong Kong counterpart (and increasingly Taiwan) became more and more of a grey area which remains impossible to completely untangle even today.

The reasons for this were largely rooted in reality. In 1979 president Park Chung-hee, who at this point was defined by traits more associated with a dictator than a president, was assassinated, which led to hopes that South Korea could finally become a real democracy. Those hopes were dashed when, in 1980, the director of the Korean Central Intelligence Agency, Chun Doo-hwan, pulled off a military coup that ousted the short-lived president Cho Kyu-ha, putting himself forward as the sole candidate to replace him. The events that led to such a grim point in Korea’s history involved Doo-hwan ordering the indiscriminate killing of hundreds (some say thousands) of pro-democracy protestors in Gwangju (in what became known as the Gwangju Massacre), and Korea would have to wait another 7 years to achieve the democracy it so strongly desired.

While in power Doo-hwan doubled down even more on restricting artistic impression through mediums like film, and placed a stronger quota on the number of foreign productions that could be shown each year. It was through these circumstances that the age of the fake co-production came about, the result of which saw the gradual dilution of the taekwon-action genre. With Hong Kong kung-fu movies still being massively popular in early 80’s Korea, distributors were keen to find a way to still show them, even if the foreign production quota had already been exceeded. Since co-productions were still classed as Korean, the ‘fake co-production’ was achieved through some mild deception and ingenuity on the part of Korean distributors.

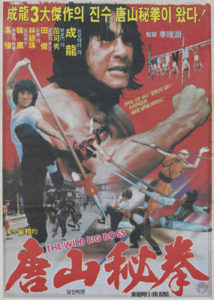

Leveraging the fact so much Korean talent was active in Hong Kong and Taiwan, when the time came to present the production to the government for screening approval, they’d emphasise the names of the Korean cast, add a fake Korean co-director, and re-title the original name. In doing so, they could successfully disguise productions which were 100% Hong Kong or Taiwanese movies as fake co-productions, and safely show them on the big screen. So the likes of a Jackie Chan movie such as Dragon Fist became The Wild Big Boss, co-directed by Lee Jeong-ho. It was well known at the time that studios like Golden Harvest were aware of this practice, however for their productions to be screened they were willing to turn a blind eye, and even today confusion remains as to what movies were genuine co-productions and which ones were fake.

There was an even more left of field approach that some studios came up with though. For those Hong Kong and Taiwanese movies that were shot in Korea (regardless of if they were genuine co-productions or not – just to add another layer of grey!), sometimes once the foreign crew wrapped up filming and returned home, the Korean crew would use the footage to shoot their own movie! The final product varied greatly, with some movies maintaining their basic plot but simply adding additional scenes with Korean actors (such as 1983’s Shaolin vs. Lama), while others created an entirely different plot (and sometimes even genre!). The best example of the latter is 1985’s Hwang Jang Lee featuring Ninja in the Dragon’s Den, which was released in Korea as Black Dragon’s Last Warning, and cut out Jang Lee all together!

Helmed by Nam Gi-nam, the fact that the Korean version chopped the appearance of the most fearsome kicker to grace the screen is perhaps the most telling sign that, by the mid-1980’s, taekwon-action and the stars associated with it were no longer the flavour of the month. Before the sun set on Korea’s high kicking genre though, the early 80’s generated one of its final stars. A surprising latter era breakthrough came in the form of Jeong Jin-hwa, who became known in the west under the amusing moniker of Elton Chong. One of the original batch of auditions for Lee Doo-yong back in 1973, Chong can be seen in the background of many a Han Yong-cheol, Bobby Kim, Casanova Wong, and Dragon Lee production, usually as a lackey whose job it is to be on the receiving end of one of their kicks.

However while the shadow of Bruce Lee was inevitably felt over any martial arts related production during the 70’s, in the 80’s it was the Jackie Chan style of kung-fu comedy that came to dominate what audiences wanted from a fight flick. With the established taekwon-action stars having already retired, working predominantly in Hong Kong or Taiwan, or having too much of an embedded onscreen persona to change, director Kim Jung-yong decided it was time to bring Chong to the fore as Korea’s answer to Jackie Chan. Throughout the early 80’s together Jung-yong and Chong became the director and star equivalent to the taekwon-action genre that Lee doo-yong and Han Yong-cheol where in the 70’s, with titles like The Shaolin Chief Cook and its sequel The Return of the Shaolin Chef bringing success at the domestic box office.

Unlike the early taekwon-action productions though, these latter Jackie Chan inspired efforts frequently drew the wrath of Korean critics, who gave them the ignominious label of being “fake kung-fu films”. The setting such stories took place in drew even more ire, with characters wearing Chinese style clothing and even the Shaolin Temple being referenced, which many critics claimed were poor attempts at fooling audiences into believing they were going to watch a Hong Kong kung-fu movie. It was difficult to disagree with the fact the confusing settings that replaced the once distinctive locales of Manchuria or contemporary Seoul inevitably resulted in the Korean identity, one that was once considered an important part of such productions, being gradually eroded away.

What couldn’t be denied though is that even if every other factor supported the “fake kung-fu film” label, the most important one – the fights – were still undeniably grounded in taekwon-action, with furious footwork being the order of the day. While the collaborations between Elton Chong and Kim Jung-yong often resorted to teeth gratingly bad comedy, supplemented by endless gurning, the fight choreography on display is some of the most complex and fast to be found in the genre. Frequently choreographed by onscreen partner Wang Ryong (who usually turned up as some variation on Sam Seed), the final fight in 1982’s Mu-rim Beggar Warriors is as good as it gets in terms of taekwondo focused choreography, and is enough to make one wish Chong had been pushed to forefront prior to the kung-fu comedy boom.

Such was the popularity of Chong with audiences that he himself would be imitated, if somewhat unsuccessfully, when in 1982 Seo Byeong-heon was pushed as Korea’s next comedic “fake kung-fu” star with a rip-off of The Shaolin Chief Cook, titled Water Retailer of Shantung. Byeong-heon was billed as Benny Tsui in the west, and had up until this point been one of the countless taekwon-action leading men who floated around in lower budgeted productions like So-kwon Martial Arts and Raging Master’s Tiger Crane. It was the latter that pitted him against Hwang Jang Lee, and more than likely gave the impetus to push him further into comedy territory, however after 2 sequels to Water Retailer of Shantung – Shantung Chinese Restaurant from the same year, and Gay Woman of Shantung in 1983 – he’d disappear from the film industry.

By the time the mid-1980’s rolled around Chun Doo-hwan was keen to do all he could to erase the populations memory that his presidency had started with a massacre of countless innocents, and to that end he introduced the ‘Three S’ policy, which referred to sex, screen, and sports. Essentially intended to take people’s minds off the countries troubles, for the film industry at least, while any criticism of the government was still strictly off the table, what it did mean is that censorship around onscreen nudity and sexual activity was loosened considerably. The policy would ultimately give rise to the erotic cinema boom that many associate with Korean cinema of the 1980’s, and which arguably acted as one of the final nails in the coffin for the taekwon-action genre, as racy dramas and raunchy period pieces began to dominate screens.

For the stars of the taekwon-action genre who were still active, there weren’t too many options left on the table. Elton Chong, who probably felt like he’d fallen out of favour just as quick as he’d fallen in, was one of the few who attempted to make the transition from taekwon-action leading man to erotic leading man. Sticking with director Kim Jung-yong, the double bill of 1987’s The Double Trumpets in the Nation and 1988’s Double Bed Commotion looked to combine both action and erotica, however audiences weren’t buying it, and after the latter Chong would retire from the film industry.

For the likes of Hwang Jang Lee, he’d return to Hong Kong in 1986 and for the rest of the 80’s would work there exclusively, starring opposite Sammo Hung in the likes of Where’s Officer Tuba? and Millionaire’s Express. For the rest, it would be kids movies that provided solace for any taekwon-action stalwarts who weren’t ready to quit the film industry, with Korea’s wacky approach to children’s entertainment best described as a riff on Japan’s tokusatsu genre. Only with lower budgets and more outlandish ideas (just check out 1989’s Our Friend, Power 5, which features the Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles as aliens who crash on Earth). The likes of Kim Young-il (aka Eagle Han Ying) would turn up in The Meteor Prince from the Milky Way 3, while Kwon Il-soo would appear in Super Hong Kil-dong 3, and even Casanova Wong would take a part in The Telepathic Journey.

While in the latter half of the 1980’s taekwon-action was largely missing in action, as the director who essentially created the genre, it would once more be Lee Doo-yong who tried to keep Korean action alive. With 1985’s Crazy Boy there was an intentional shift to move away from taekwon-action, and move towards the kind of physical action and stunt work that Jackie Chan was popularising with the likes of Police Story. Leveraging the physical talents of Jeon Yeong-rok, an actor and singer who’d already been popular since the 70’s, Doo-yong utilised his physical dexterity in a way no other director had done before, which went so far as to see him labelled as the Korean version of Jackie.

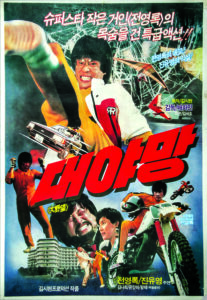

Crazy Boy was a massive success, with the mix of car chases and stunt work feeling like a breath of fresh air for local audiences, and the rest of the 80’s would spawn 3 sequels (although Doo-yong only returned to direct the 2nd , and neither Doo-yong or Yeong-rok would return for the 4th). For a while it seemed Yeong-rok had successfully re-branded himself as the new face of Korean action, turning up in titles like The Great Ambition (in which he’d sport a variation of Bruce Lee’s Game of Death yellow tracksuit!) and A Self-Righteous Man, however by the early 90’s he also retired from the film industry to focus on his music.

While it may have seemed taekwon-action had become a genre of the past, as an interesting footnote it would make somewhat of a comeback in the 1990’s. After director Im Kwon-taek would set the template for the modern Korean gangster movie with The General’s Son trilogy which spanned 1990 – 1992 (read our full feature on the trilogy here), the productions unmistakable taekwondo styled action sequences saw high kicking heroes regain their popularity. The knock-on effect would see many of the taekwon-action genres biggest stars make a return to the screens, embracing the gangster genre as a means of framing the action.

Suddenly the likes of Casanova Wong, Hwang Jang Lee, and Dragon Lee started showing up sporting fedora hats and trench coats with oversized shoulder pads, but as different as they may have appeared from their heyday, the one thing they all had in common was that they could still kick it. Just as the 1970’s were a distinctly different beast from the 1960’s, so the 1990’s proved to be a very different era in Korea from the 1980’s. In 1987 Chun Doo-hwan was finally ousted and South Korea would become a democracy (which it’s never looked back on since), in 1988 they’d host the Olympics, and for the film industry there were also changes. Censorship was lifted, quotas on foreign cinema were eased, however most significantly for the takewon-action veterans of previous decades, there was a new popular kid on the block – the VHS.

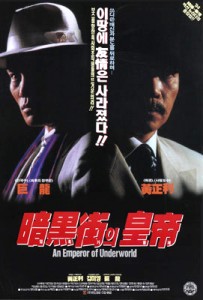

While they may no longer have been the box office draws they once were, the 1990’s offered a new home in the world of direct-to-video, and many of the talents from yesteryear would use the new format to try their hand at furthering their directorial skills. Casanova Wong unleashed Jongno Blues and Bloody Mafia, Hwang Jang Lee would helm Emperor of the Underworld (which gave him another round against Dragon Lee!), while Kwon Il-soo would direct the Dragon Lee starring The Nationwide Constituency trilogy. The straight-faced machismo of such productions in many ways brought the taekwon-action genre full circle back to its 1970’s origins, with the steely faced gangsters that now populated the screen echoing the similar gazes that once belonged to the likes of Han Yong-cheol and Bobby Kim.

What can’t be denied is that as a genre, taekwon-action was as distinctive to Korea as the karate movie is to Japan, and the kung-fu flick to Hong Kong. Born out of compromise, the result was a roster of stars who remain engrained in the memory of martial arts cinema fans to this day, even if not all of them may be aware of the history of the genre to which they belonged. Hopefully this feature will at least do a little to shed more light on taekwon-action, allowing us to celebrate the thrills of the most lethal kicks to grace the screen, despite the hardships that were being endured while they were being made. Taekwon-action forever!

Author’s note: The productions referenced in this feature have used the original English title translation of the Korean name, however many taekwon-action movies were distributed in the west by the like of Asso Asia under different names. Frequently re-edited and cut, despite this many of these versions remain the only way to view such productions (not only for an English-speaking audience but also Korean!). For convenience, in such instances we’ve hyperlinked the title to either one of our existing reviews, or the entry at the Hong Kong Movie Database which lists the (frequently more than one!) western release title.

Fascinating article. Thank you for putting in the research. I will try and seek out some of the earlier titles.

It’s such a shame that so many of these titles only exist in VHS quality.

Thanks for the comment Kashif! The good news is 2 of Han Yong-cheol’s early movies, ‘Returned Single-Legged Man’ and ‘The Manchurian Tiger’, are fully remastered in HD with English subtitles and available on the Korean Film Archive’s Korean Classic Film YouTube channel. Check them out via the links –

Returned Single-Legged Man – https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MCAEErEhDHQ

The Manchurian Tiger – https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=li72N-RzJ60

Im always at this website and never have time to post lately due to my hectic schedule. So i wanted to take the time out of my busy schedule to let you know that I enjoyed this article. It sheds lots of light on why Koreans are showing up in the many kung fu classics I grew up watch. As good as Bey Logan and Brandon Bentley’s stuff. Nice research. I have to see some of these Dragon Lee gangster movies.

Thanks Scott, glad you enjoyed it, and COF appreciates your patronage!

ironically saw this article the day Lee Doo-yong died. good writing (kind of article handling this topic is hard to find even in south korea)

Thanks rmon, and it’s by pure coincidence that this feature was posted on the same day Lee Doo-yong passed away. RIP to one of Korean cinemas true greats, I dedicate this feature to him, and hope it prompts anyone whose unfamiliar with his work to check it out (both Han Yong-cheol movies linked in one of the previous comments are directed by Yoo-dong!).

I think you covered the different eras very well and even getting into the politics behind it. It’ll be a very valuable information piece for those new to the Korean films or with just a little knowledge as it’s very difficult to find anything on them, even now.

It is very good, you really did go into pretty much all the ins and outs of it, even addressing the whole “fake co-productions” controversy, I’ve had to deal with that a bit on HKMDB, with people trying to assert they’re all fake credits, despite me showing them Korean cut’s with alternative scenes etc. We just don’t know and probably never will.

All in all, you’ve done a damn good job of it.

Cheers

This certainly is a bygone era! At first I was excited about the lower budgeted martial art films coming out like Master Heaven and Real Fighter, and it was a shame that they sucked so much. I like to think that South Korea could still make a taekwon-action film as a tribute to this era much like Dachimawa Lee was.

I love how the “Golden Gate” poster is just the one for “To Kill With Intrigue” with Wong’s face pasted over Jackie Chan’s!

My favourite Korean poster will always be 1978’s ‘Blood of Dragon Peril’, which uses the poster for the previous years ‘The Gauntlet’, swapping out Clint Eastwood’s face for Chang Il-do!