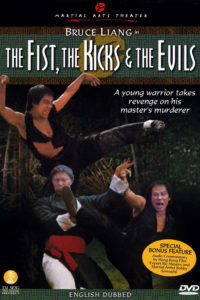

AKA: Fists, Kicks and the Evils

Director: To Lo Po

Cast: Bruce Leung Siu Lung, Philip Ko Fei, Bolo Yeung Tze, Chiang Cheng, Ku Feng, Lau Hok Nin, Ma Chao, Chan Lau, Lin Ke Ming, Kei Ho Chiu, Ricky Wong

Running Time: 84 min.

By Matthew Le-feuvre

In that rare and exclusive echelon of celebrated kicking tacticians, Leung Siu Liang – otherwise known in international circles as Bruce Leung – seemed to be throughout his career designated at the lower end of the martial arts acting fraternity, despite (or in spite of) spearheading or supporting a myriad of fight legends, notably: Jackie Chan (Magnificent Bodyguards); Angela Mao Ying (Broken Oath); Ho Tung Tao (Bruce vs. Iron Finger) to the more recent Stephen Chow film (Kung Fu Hustle). Observedly, his only problem – per se in securing instant recognition – was a diminutive stature.

Moreover Leung was neither physically blessed with a standard “action man” persona, nor was he photogenic in a way many of his contemporaries were, at least from a matinee idol perspective. What Leung had to offer was an affable disposition bordering on the goofy; an everyman in equal semblance of an outsider caught between political subversion and paternal revolt until conditions intercede the presence of a wise and patient master. These were commonplace building blocks to the majority of Hong Kong/Taiwanese screenplays: ergo the maturity of the underdog who breaks the shackles of oppression by (A): resisting exoteric influences to (B): learning an arcane combative doctrine.

Leung’s adequate career more or less treaded a conventional path. Born in 1948 and raised in Hong Kong, he learned the rudiments of kung fu from his father, a well respected Canton Opera Sifu, prior to augmenting his physical perspicuity in both the Wing Chun and Goju Rye systems. As a veteran of 75 films (to his credit), Leung originally acquiesced to a typical contract with the Shaw Brothers scraping a meagre, often toilsome living as an expendable extra/stuntman: look carefully, and he can be glimpsed assailing the now-long forgotten Shi Szu in The Lady Hermit (1971).

With timed regularity, Leung eventually graduated to larger or more meaty support roles before landing critical lead vechicles, for example Kidnap in Rome (1976), opposite the generally overlooked Mang Hoi; My Kung Fu 12 Kicks (1979) and the rather distasteful Bruceploitation romp, The Dragon Lives Again (1976). Surprisingly the latter did less damage to Leung’s profession than one would gather. Yet the very concept of promoting a metaphysical dimension in which Lee’s spirit combats a hierarchy of nefarious archetypes from ‘Dracula’ to a ‘Clint Eastwood’ imitator was indeed an exercise in derision, at best, skirting on levity. However, regardless of a variably indistinct filmography, perceptively, the equivalent could not be affirmed of The Fists, the Kicks and the Evil.

Set against the backdrop of those ordinarily haughty ‘Manchu’ (Qing) subjugators, Leung reunites with (the frequently referred) Schlockmeister, To Lo Po (Fist of Fury 3) for a physically eruptive, superbly choreographed tale of loss and retribution. Nevertheless these script ingredients are requisite despite an almost pedestrian feel as the story arc, in part, is loosely based upon the formative years of Wong Yan Lam – apparently one of the founding members of the legendary ‘Ten Tigers of Kwantung’. Although Lam’s latter real-life exploits were objectively as well as collectively motivated on restoring the ‘Han’ administration, here, the premise is undividedly focused on Lam’s schooling in the graceful art of (Lama) White Crane Kung Fu, an extremely complex, yet pliant style where the rigorous demands of honing wrist/finger strength whilst the hands are emulous of a crane’s beak is equally important as balance and co-ordination.

The beauty of this picture, which for some maybe contentiously unoriginal or repetitive even, is Lam’s metamorphosis from a rambunctious neophyte filled with misdirected anger towards, intrinsically, a political ideology based on class discrimination into that of a disciplined, confident fighting tactician. Naturally there is always in place ‘a catalyst’ for Lam’s external transformation. In this case (a familiar theme not always saluted by critics), it is the unprovoked, as well as blatant, patricide of his father played, nonchalantly, by the (consistently) great Ku Feng, an actor who by general occupation was under a very strict contract with the Shaw Brothers. Here, Feng was allocated creative manoeuvrability to engage outside the machination providing it was conducted in a minor capacity.

Refreshing, though obligatory, as principle Manchu nasties – support from the otherwise ice-cold Ko Fei (Techno Warriors) and his sadistic subordinate, the ever voluminous Bolo Yeung, each chew up recognizable Taiwanese sceneries, and/or extant locales with gleeful abandon. Negligible… perhaps?! But all essential paradigms, right down to the basics of staid dialogue and formulaic typecasting. Of course, neither would amicably work without the other – a sort of symbolic scaffold for an obviously innovative conclusion whereby Lam deftly manages too ‘showcase’ as well as ‘negotiate’ his manifold techniques within a bamboo forest. Dazzling!

Matthew Le-feuvre’s Rating: 9/10

classic slice of kung fu cinema, always loved this movie and then when i came to Hong Kong one of the first people i became friends with was the late great Rambo KK Kong (Kong Kwok-keung) who plays the mischievous mercurial master who teaches Bruce Liang….