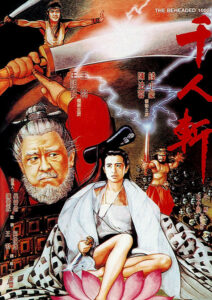

AKA: The Executioner

Director: Ting Shan-Hsi

Cast: Jimmy Wang Yu, Chin Siu-Ho, Joey Wong Cho-Yin, Monica Chan Fat-Yung, Wu Ma, Pauline Wong Siu-Fung, Sun Ya-Tung, Shen Hai-Rong

Running Time: 105 min.

By Paul Bramhall

One of the more intriguing propositions to come out of the early 90’s, on the surface at least The Beheaded 1000 offers up a Taiwanese take on the Hong Kong blend of wuxia and fantasy that it did so well at the time. The blue lighting is prominent, there’s a wacky assortment of characters, and there’s even a raft of imported HK talent like Chin Siu-Ho, along with A Chinese Ghost Story luminaries Wu Ma and Joey Wong (ok, technically she doesn’t count because she is Taiwanese, but we’re going with it). However looks can be deceiving, and those clocking in expecting the typical new wave wuxia style madness involving ridiculously complex wirework, silk billowing in slow motion, and bodies exploding into colorful powder, may leave disappointed.

The Beheaded 1000 would mark the 10th and final collaboration between director Ting Shan-Hsi and star Jimmy Wang Yu, a partnership that had endured for more than 20 years. Not that their collaborations were necessarily well spaced out. After working together for the first time as director and star on 1972’s Furious Slaughter, over the course of the same year and 1973 they’d crank out 7 titles, including the classic Knight Errant. It wouldn’t be until 1976 that they’d cross paths again, with Shan-Hsi pairing Wang Yu alongside George Lazenby in the unforgivable snooze fest that was A Queen’s Ransom, and a year later he’d cast Wang Yu alongside Angela Mao and Don Wong Tao for Revenge of Kung Fu Mao. It would take 16 years would for the pair to work together again, when Wang Yu came onboard once more for Shan-Hsi’s penultimate turn in the director’s chair, with 1993’s The Beheaded 1000.

While many of their previous collaborations were stripped down, action driven pieces of entertainment, The Beheaded 1000 seems to suffer from a split personality, not really being sure what it wants to be, and with a plot that doesn’t help its cause in any way. In a nutshell Wang Yu plays an executioner whose preferred method is beheading, and he’s planning to retire once he hits 1000 executions, handing over duties to his apprentice, played by Chin Siu-Ho (Fast Fingers, Fist of Legend). However the plans for an easy transition to retired life are interrupted by the arrival of a vengeance seeking member of the Blood Clan, played by Joey Wong, several of whom have fallen to Wang Yu’s blade. Of course, as its Joey Wong, matters are complicated further when a constable falls for her, but she may be in love with Siu-Ho, who actually has eyes for Wang Yu’s daughter. Can true love prevail when this many heads are rolling?

In fairness, by the time Wu Ma arrives as the Guardian of Hell who just wants to marry off his sister (played by another HK presence in the form of Mr. Vampire’s Pauline Wong), the type of head rolling coming from the audience may well be one of exasperation. Did I mention there’s human pork buns in the mix too? What exactly the focus is supposed to be of the main plot is open to debate, however I’ll take a stab and say it’s about Wang Yu battling against the Blood Clan to bring them to justice. Ask someone else and they may have a completely different answer, as there’s so many seemingly meaningless tangents that The Beheaded 1000 constantly struggles to find an engaging narrative flow. This feels like the result of a director steeped in the past, but with an obligation to create a movie which reflected the popular themes of the era. As a result though, there are parts that thanfully do work effectively.

The legendary status of Wang Yu’s executioner is shown via the way he performs his beheadings so swiftly, none of his prisoner’s heads who have been on the receiving end have ever hit the ground. Instead, he catches the head mid-air (the wuxia stylings mean that these types of beheadings see the head fly up into the air having been sliced off, rather than simply drop to the ground as gravity would dictate), place it back onto the still kneeling torso, and wrap a yellow talisman paper around the part of the neck that was cut. That’s how to behead in style. There are quirky elements like this scattered throughout, including when Siu-Ho steps up to complete his first public beheading, which will be that of a hulking behemoth played by Lin Hsieh-Wen (A Heroic Fight, Kung Fu Kids IV). When the beheading goes wrong due to Hsieh-Wen’s considerable girth, he ends up stampeding around town with a sword amusingly embedded in his neck.

Such scenarios in any similar movie of the era would be where the action choreography comes to the fore, however here the action is a surprisingly muted affair, to the point where the usual sources such as the Hong Kong Movie Database don’t even list an action director. It’s beguiling since various scenes indicate there’s an experienced hand behind the camera, and if I was a gambling man I’d be willing to bet that the action was likely handled by assistant director Alexander Lo Rei of Ninja Final Duel and Ninja Condors fame. We get Joey Wong floating through the skies strapped to a massive white kite, and some entertaining training sequences between Wang Yu and Siu-Ho, one of which has Wang Yu casually kicking barbells in Siu-Ho’s direction as he strolls around like they weigh nothing!

However any actual choreography is basic, and feels like it wouldn’t be out of place in Shan-Hsi’s efforts from 20 years earlier like 1969’s The Avenger or 1971’s The Ghost Hill. A few clangs of the sword seem to be the order of the day, further enforcing the theory that The Beheaded 1000 doesn’t really know what it wants to be. In the end, to enjoy Shan-Hsi and Wang Yu’s final collaboration the best thing to do is to attune to its wavelength and simply go with the flow. For fans of Joey Wong it’s a rare opportunity to see her as a villain, and she’s surprisingly cruel. In one scene the constable who’s in love with her proposes that they find somewhere serene far away and start a new life together, to which her response is to castrate him and mockingly say “how’s this for far and serene?”, before leaving him to bleed out.

Most bewildering is when Wang Yu eventually does retire, and opens a small restaurant with his family. When the ghosts of the Blood Clan members that he beheaded turn up to confront him, he shows a Steven Seagal-level lack of surprise in his facial expressions, and instead invites them to sit down. The scene gets increasingly absurd, as one of the ghosts rips out the others intestines and offers them as a gift, and there’s even the arrival of a flying gremlin that attacks Wang Yu, before he calmly pulverizes it in a way that reminds us that, hey, this guy is Wang Yu, don’t screw with him even if you’re a demonic gremlin.

All of this culminates in a finale that never feels entirely clear in terms of what’s at stake, but chances are anyone who sticks with the lengthy 2-hour runtime will have already tempered their expectations by this point. There is fun to be had – Chin Siu-Ho finally brandishes Wang Yu’s legendary sword and gets some brief bursts of action, there’s a bunch of oversized animated green spiders to battle against (which weirdly on the version I watched, crawled over the black widescreen bars, giving them an oddly 3D effect), and at its most absurd we get Wu Ma and Wang Yu turn into kaiju sized versions of themselves. Sadly anyone expecting to see a kaiju sized Wang Yu going on a Godzilla style rampage will feel let down, as he mostly sticks to dispensing wisdom and busting out a few strokes of the sword.

Ultimately The Beheaded 1000 feels likes a production that wants to have its cake and eat it – we get doses of kung-fu, elements of Cat III, ghosts, comedy, some romance, a random gremlin, and sudden bursts of violence. However if the cake was made with only half-baked ingredients in the first place, no matter how many more you throw in it’s never going to make it taste any better. While there’s a welcome nostalgia to seeing director Ting Shan-Hsi and Jimmy Wang Yu back together, the meandering focus and disjointed narrative make it difficult to recommend.

Paul Bramhall’s Rating: 5/10