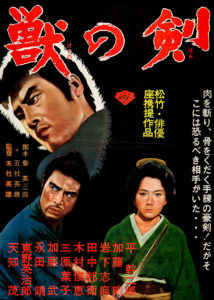

AKA Samurai Gold Seekers

Director: Hideo Gosha

Cast: Mikijiro Hira, Go Kato, Toshie Kimura, Kantaro Suga, Takeshi Kato, Shima Iwashita, Yoko Mihara, Shobun Inoue, Kunie Tanaka, Eijiro Tono

Running Time: 85 min.

By Henry McKeand

“I want to become a beast like you. I can’t stand living for a mission anymore.”

While Hideo Gosha has never come close to reaching the same level of Western acclaim as Akira Kurosawa, his 1960s chambara (“sword-fighting”) films positioned him as one of the most influential Japanese directors of his time. As opposed to Kurosawa, who saw feudal Japan as an epic tapestry, Gosha created pared-down films about morally ambiguous swordsmen. This trend was established in his first feature, Three Outlaw Samurai, and it continued into his sophomore effort, the blistering Sword of the Beast. While much of samurai cinema focuses on the flaws of feudalism, Sword of the Beast is a particularly scathing portrayal of samurai hypocrisy. Clocking in at less than 90 minutes, it’s also an example of early action filmmaking at its most thrilling and economical.

The film centers on the disgraced Gennosuke, played by the exceptional Mikijiri Hiro, who is on the run after assassinating a counselor from his clan. After escaping from a group of his clan’s swordsmen, he teams up with a scheming farmer named Gundayu and embarks on a quest to steal the shogun’s gold. This causes him to cross paths with an idealistic samurai named Yamane and his wife Taka, who are working together to steal the gold for their own clan. Soon, Gennosuke’s allegiances are tested when he learns more about Yamane and his situation.

It would be a dense plot for any film, let alone one as short as Sword of the Beast. Thankfully, Gosha is a master of efficient storytelling. He is never weighed down by the impressive cast of characters, which includes bandits, vengeful daughters, and ruthless mercenaries. Every plot development is in service of the themes of sacrifice and hypocrisy, and there isn’t a wasted moment in the film.

Genre movies as finely tuned as this can feel mechanical, but the story of Gennosuke pulses with emotional intensity and complex motivations. And while the narrative is at times bleak, with the greedy Gundayu offering the only comic relief, there’s an undercurrent of humanity in the script and performances that prevent it from being an entirely nihilistic affair. These are fully realized people who just so happen to be experts at chopping through flesh.

Still, the characters are eventually forced to do what they’re best at, and there is plenty of bloodshed to be found. The combat scenes are visceral and exciting, with Gosha frequently filming the action in wide shots that beautifully capture every impressive movement. The fight scenes are tightly choreographed without ever feeling overly rehearsed; this is due in large part to Gosha’s emphasis on constant motion. Duels are consistently broken up by characters running away in search of a better foothold, and there’s something thrilling about seeing samurai sprint at full speed with their swords at the ready. Refreshingly, there’s zero vanity in the choreography, with the performers unafraid to play dirty or use a sloppy move to come out on top. The result is a movie filled with sword fights in which everyone seems to be desperately trying to survive.

Despite being mostly absent of blood and gore, Sword of the Beast is an at times brutal experience. It may not hold a candle to the ultraviolence of certain later samurai films, but the black-and-white imagery belies the uncompromising approach to feudal conflict. The film feels like an angry, radical statement even today, thanks to its rejection of unearned sentimentality and its skepticism of hierarchical power structures.

Furthermore, it’s beautiful to look at; Toshitada Tsuchiya’s cinematography brings the Japanese countryside to vivid life, and the direction is dynamic during both the slow and frenetic segments of the film. To keep things fresh, the set pieces make great use of the environment, as multiple fights are staged in tall grass or on riverbanks. Without being showy, Gosha turns a very literal story into something that’s layered and visually engaging.

For those of us spoiled by the nonstop stimulus of modern action cinema, going back and watching the films that paved the way can sometimes feel underwhelming. Here, this couldn’t be further from the truth. There’s something about the inventive plotting, mature characterization, and gritty action that make Sword of the Beast a thrill for any fan of Japanese cinema or action movies in general.

Henry McKeand’s Rating: 9/10