Director: Junta Yamaguchi

Cast: Riko Fujitani, Yuki Torigoe, Yoshimasa Kondo, Haruki Nakagawa, Masahi Suwa

Running Time: 86 min.

By Paul Bramhall

Making a follow-up to a debut that relied heavily on a gimmick is always a tricky proposition, as several directors have found out over the years. In Japan the most obvious example is Shinichiro Ueda, who after his almost flawless debut with 2017’s One Cut of the Dead has struggled to replicate the winning formula with subsequent efforts, and in 2023 director Junta Yamaguchi released his sophomore feature River. Coming 3 years after Beyond the Infinite Two Minutes, Yamaguchi’s debut centered around a café owner realising the monitor in his room upstairs is capable of showing 2 minutes into the future, the inconsequence of which is utilised to amusing effect. In my review I’d mentioned how it uses the time travel plot device in a “more minutiae way than any of its predecessors (and perhaps anything that’ll come after it)”.

Well, with River I’ve already being proved wrong, as rather than try something completely new, Yamaguchi has returned to the concept of 2-minute time travel for his sophomore feature. He’s also stuck with Japan’s apparent time travel specialist script writer, Makoto Ueda, who penned Beyond the Infinite Two Minutes and 2005’s Summertime Machine Blues (which received a semi-sequel in 2022 in the form of the anime limited series Tatami Time Machine Blues). However with River it’s not just a couple of rooms experiencing the time glitch, but a whole town. To his credit, Yamaguchi isn’t repeating (pun intended) himself with his sophomore feature, but rather taking the idea of how to play with time travel in a cinematic sense, and both refining as well as being more ambitious with the concepts and scale Beyond the Infinite Two Minutes was limited to.

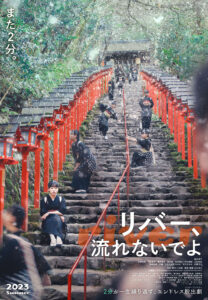

While in his debut the characters found themselves talking to themselves 2 minutes into the future through a TV screen, in River the concept is switched up to focus on a hot spring inn (or ryokan for you Japanophiles out there) in the rural village of Kibune, Kyoto that finds itself jumping back in time every 2 minutes (or as one character explains, it’s a time loop rather than a time leap). Here the characters “consciousness continues”, so while their physical location keeps on resetting to where they were 2 minutes prior, everyone is aware they’re stuck in a time loop. The scenario results in the narrative thrust becoming the characters attempts to stop the loop and make time revert back to normal service, but with only 2 minutes each time before everyone finds themselves back where they were, everyone starts to understandably become increasingly strained.

Yamaguchi gives himself a significantly broader canvas of characters to work with this time, with the closest thing to a main character coming in the form of Riko Fujitani (who also featured in Beyond the Infinite Two Minutes), playing a worker at the ryokan who we first meet (but will have met several times more by the time the credits roll) taking a breather at the river running along the back when the loop starts. Amongst the guests there’s a chef from the restaurant across the street taking a rest in one of the rooms (played by Yuki Torigoe – Bungo Stray Dogs the Movie: Beast), a frustrated writer (played by Yoshimasa Kondo – Love and Other Cults), and a whole bunch of returning cast members from Beyond the Infinite Two Minutes – including a persistent publicist (Haruki Nakagawa) and a couple of friends who used to be business associates (Masahi Suwa and Gota Ishida).

For his sophomore feature the notable difference from Yoshida’s debut is that there’s more of a focus on the human elements of the story, rather than a reliance purely on the technical execution of the gimmick to keep the audience engaged. It’s a welcome one, and makes the characters feel more relatable than those in Beyond the Infinite Two Minutes, with as much attention paid to how the time loop is affecting each one of them within the context of their own life, versus simply watching them react to the situation itself. It dawns on the writer that he has a deadline that’ll never come, the friends realise they have more time to drink together away from their busy schedules, and a romance that seemed to be coming to an end is placed on indefinite hold. Each character has a reason to cling onto the fact that time keeps going back on itself, but ultimately mileage varies as to how long they can enjoy it before tensions start to fray.

The broader scope of River also sees Yamaguchi expanding his palette to a variety of genres through the background of each guest, hanging them off the sci-fi framework the story takes place in, and therefore avoiding falling into the trap of being a one-trick pony. From comedy (including the funniest post-suicide scene you’re likely to ever see), to drama, to romance, and there’s an undeniable charm in River’s distinct Japanese-ness. Only in Japan would you see a scenario play out in such a way that after only the 3rd loop (so 6 minutes in) the staff’s first thought is to attend to the guests, with one of the major dilemmas they have to overcome being that the warm sake the 2 friends ordered still isn’t warm enough to serve at the point that time loops back.

The seemingly trivial matters are what draws some of River’s best comedic moments during the first half of its punchy 85-minute runtime, including dealing with the writer whose taken to trashing the room he’s staying in, safe in the knowledge it’s going to reset back to exactly the way it was a few seconds later. While it’d be an exaggeration to say that the plot gets a lot more serious in the later half, it does at least present an emotional core as to why the time is looping, giving the audience a motivation anyone can empathise with, and in turn a deeper connection to what’s playing out onscreen. In fact Yamaguchi does this so well that it’s possible to dismiss how exhausting it must have been to actually film, considering that (and I didn’t count, but let’s just base it on the runtime) Fujitani in particular must have completed variations of the same take around 60 times.

Indeed while River is still a low budget affair (although it’s clearly got more funding behind it than Beyond the Infinite Two Minutes, which was shot entirely on an iPhone!), once more it’s the skill of a filmmaker like Yamaguchi who proves that budgetary constraints don’t always need to be a barrier to creativity. It’s a credit to both those behind the camera and in front of it that not once does the illusion of the 2-minute loop break, with the concept remaining entirely believable from start to finish. As the anchor of the piece Fujitani serves as an effective audience avatar and makes for an endearing screen presence, clocking in a leading role that’ll hopefully act as a calling card that means we’ll see more of her. From the cool and collected approach she initially takes to the situation, to the increasing toll it begins to take once the source of the loop is revealed, she’s a joy to watch.

Ultimately the finale makes a connection to the same universe that Beyond the Infinite Two Minutes takes place in, and while on initial viewing I felt disappointed that it didn’t follow through on some of the reasoning presented earlier, on 2nd viewing I realised it doesn’t actually change any of the ideas presented. The metaphor of the flowing river may be an obvious one (the full Japanese title translates to River, Don’t Drift Away), however Yamaguchi delivers it in a way that’s bound to resonate. Crafting a tale that uses its sci-fi leanings to acknowledge the comfort in the familiar trappings we sometime seek as humans, and the inevitable hurdles we place in front of ourselves if we never seek to explore outside of them. In the end it’s the decision we make to move forward and push on into the unknown that makes us who we are, and in turn River serves as a light-hearted microcosm for life itself.

Paul Bramhall’s Rating: 8/10