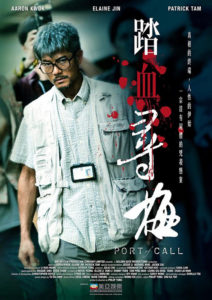

Director: Philip Yung

Cast: Aaron Kwok, Elaine Jin, Patrick Tam, Jessie Li, Michael Ning, Jackie Cai, Maggie Shiu, Eddie Chan, Hatou Yeung, Ellen Li, Don Li, Ronny Yuen, Tam Ping-man

Running Time: 120 min.

By Paul Bramhall

Port of Call is something of an anomaly for the year in which it was made, being a Category III Hong Kong production which received no financing from the Mainland. The end product is one that will remind audiences familiar with the territories output just how much that distinctive Hong Kong atmosphere has been missed. Invoking a feeling though isn’t enough to make a good movie, but thankfully director Philip Yung’s third feature also happens to be an enthralling piece of cinema, equal parts murder mystery and character study.

Yung is one of a handful of new voices in the Hong Kong film industry, and with his output so far it’s become a voice that reflects the disenchantment of the territories youth, and the depths that such disenchantment can lead to. Much like how Fruit Chan’s Made in Hong Kong captured a certain moment in time for the youth of Hong Kong in 1997, so Yung’s features echo the same for the current times we’re living in. Both his debut and sophomore features, 2009’s Glamorous Youth and 2013’s May We Chat (notably also both Cat III), take place in the world of prostitution and compensated dating, and Port of Call stays in the same world.

The biggest difference is that for his latest, Yung sets the tale against the true story of a 16-year old girls murder that took place in 2008. Wong Ka-mui had come from the Mainland and ended up in the world of compensated dating, sadly meeting her end when she was strangled by Ting Kai-tai, one of her customers, who was high on ecstasy and ketamine. Unable to recall the murder when the drugs wore off, Kai-tai disposed of her body by chopping it into pieces and flushing it down the toilet, before disposing of her head off the end of a Kowloon pier.

Yung takes these events to create a narrative that frequently jumps back and forth in time to before and after the murder, focusing on a trio of characters (fictional names are used). Newcomer Jessie Li makes her debut in a challenging role, playing the fresh-faced arrival in Hong Kong with dreams of becoming a model. Stage actor Michael Ning also makes his debut on the big screen, playing the listless delivery driver who eventually hires the services of Li having been given the cold shoulder by another girl. The most familiar face in the cast is Aaron Kwok who plays the detective, however in saying that, he’s barely recognizable under a mop of greying hair, gaunt features, and oversized glasses.

Casting Kwok was arguably Yung’s biggest gamble. Despite the longevity of his career and the fact there can be no doubting his legendary status in Hong Kong, as an actor he’s only as good as the directors he works with, who need to have a firm rein on his tendency to overact. So for every Throw Down, After This Our Exile and The Detective (which his role in Port of Call most closely reflects), we have the likes of Divergence, City Under Siege, and Murderer (which has to be seen to be believed) to suffer through. Thankfully he puts in a stellar performance here, playing his character in a quietly subdued way that conveys a weariness over the amount of death he’s seen, but also exuding a quiet determination to get to the bottom of the case.

The hook for Port of Call isn’t so much the mystery of who committed the murder, it’s made clear in the early stages that it was Ning, the question is more the how and what led up to it. Ning insists that his victim asked him to kill her, and Kwok can’t seem to let it go, driven to find out if his claim could be true, and what could have led to her making such a request. Yung uses this hook to weave the narrative in and out of various timelines, as we spend time with all 3 of our main characters before they find themselves in each other’s respective trajectories. It’s this structure which gives the narrative a contemplative feel, with a runtime which isn’t hurried, allowing us to understand how each of them got to be who they are, and painting proceedings in increasing shades of grey (another welcome benefit of having no Mainland money in the production).

Speaking of the runtime, the Director’s Cut runs 12 minutes longer than the theatrically released version, clocking in at 2 hours. Which 12 minutes have been cut will be blatantly obvious to anyone that watches it, as we get to see in graphic detail how Ning disposes of the body, in an extended sequence which certainly isn’t for the faint of heart. The sequence will no doubt come with an extra jolt for those of us who’ve become accustomed to the bloodless nature of recent HK-China co-productions (check out the arm decapitation in Shock Wave for a recent example), as Yung doesn’t shy away from the gory details. It should be highlighted though that the sequence isn’t exploitative in any way, and is a world away from the gratuitous gore of Herman Yau’s The Sleep Curse which came 2 years later, feeling very much like gore for gores sake.

There are parts though which could have benefitted from some trimming. There’s a flimsy sub-plot thrown in involving Kwok’s ex-wife and his daughter, which isn’t given enough substance or screen time to mean anything, and could just have easily been removed all together with no impact. Their scenes together at least allow for that sentimental streak to show through that HK cinema of old was never able to resist, as Kwok sees the daughter of a victim from an old case grown up and working in a zoo looking happy. It’s a rare moment of hope that Yung allows to shine through in an otherwise bleak (but never anything other than engaging) tale.

For many it may come as no surprise to discover the distinctive look for Port of Call is thanks to director of photography Christopher Doyle. Having lensed so many Hong Kong productions over a period of more than 25 years, from My Heart is that Eternal Rose to Chungking Express, Doyle’s camera feels like one which knows the city intimately. There’s no gloss to the Hong Kong that’s portrayed in Port of Call, with shots often framed through stained windows, or permeated with dirt and blood. One particular dream sequence, where we find out why Kwok isn’t a fan of sleeping, is a standout in terms of shot composition and the way its framed, dragging us into a nightmare his obsession with the case prevents him from escaping from, even when awake.

Combined with strong performances from all the cast, the Hong Kong Yung paints feels like a real one. Doyle himself would go onto cast Ning in his own feature The White Girl a couple of years later, a testament to the newcomer’s performance here, which often elicits a shudder down the spine. Jessie Li is a standout. So many of these movies will often paint the victim as a collection of clichés and stereotypes, but with Li we get a fully rounded character with dreams and aspirations, while also witnessing how far she’s willing to go in pursuit to them. Taiwanese actress Elaine Kam deserves a special mention playing Li’s mother, who had no idea what line of business her daughter had gotten into, and she puts in a performance where the devastation is palpable.

Along with Edmond Pang Ho-Cheung, Yung feels like one of the few true voices that Hong Kong cinema has left, proving that the territory can still make movies that bear its own unique stamp. While the focus seems to be increasingly on small scale indie productions, the likes of Port of Call show that it’s still possible to make a taut thriller that stands up alongside the best of them. If you’ve yet to see it, my suggestion would be to fix that very soon.

Paul Bramhall’s Rating: 8/10

It’s too bad that your review of low-quality mainland tripe with Jackie Chan receives a myriad of attention from other readers, while reviews of hidden gems like this go completely uncommented on. (I realize that scathing reviews probably end up getting the most user engagement, but… still.)

So I’ll be the first one to pop in and say thanks, because I probably would’ve never heard of this movie otherwise. Sounds like it really deserves to be watched. Honestly, anything like this that proves true HK cinema isn’t dead (yet) makes me happy.

By the way, I actually just watched Project Gutenberg (2018) with Aaron Kwok a few weeks ago. Excellent movie. Kwok seems like a great actor if he has proper direction.

Hi Dan, thanks for the comment, and if the review makes just one person check it out who wouldn’t have previously, then I consider it job done! Look forward to hearing your thoughts whenever you get the chance to give it a watch.

As for ‘Project Gutenberg’, I had a slightly different opinion on that one, but understand it had its fans. Check out my review for it here.

“anything like this that proves true HK cinema isn’t dead (yet) makes me happy”

Hong Kong cinema died about 20 years ago. Deal with it. It will never come back, certainly not as during the 1970-2000 era.

By the way, you’re talking about a movie put out in…2015, already FIVE years ago.

good luck chopping off someone on ketamne XD

Gotta agree with some of the other comments. It’s no coincidence there have been no Hong Kong cinema classics since 1997-2000. Their entire industry used to be innovative and free. Now they can’t do this or that, or say whatever they want like they used to. It’s sanitized and censored. It is over.

Just like the Shaw Bros era died and never came back. HK cinema died in 1997.

Why is everyone saying HK cinema died in 2000? I’d argue 2010 was the end. There are some fantastic films released during that 2000-2009 period. In the Mood For Love, Infernal Affairs, Election, One Nite in Mongkok, On the Edge…

I agree. Hong Kong cinema had a rough time from the late 90’s to early 00’s due to talent trying their hand overseas and the rampant piracy, but it wasn’t dead, and by the mid-00’s most of that talent had returned. It was only really when the mainland started to become an economic powerhouse in the early 10’s, which led to cinemas springing up in their 1000’s, that local HK cinema found itself sidelined in favour of bigger box office returns (and the censorship requirements that became increasingly stringent to the point where, as of last year, movies can now be deemed a risk to national security).