Despite their doors being shuttered over a decade ago, Tower Records is a place that continues to loom large in many consumers’ nostalgic hearts. Don’t believe me? Just watch 2015’s All Things Must Pass, which –– while not a great documentary –– is admirably devoted to preserving the memory of the once great entertainment franchise. For media fans all over the globe, Tower served as a one-stop shop for vinyl and CDs, magazines, and other wares. Back in the pre-Blu-ray era, my local Tower was also the premiere destination for Asian films on DVD, and I spent countless weekends hoping to find the next mind-melting kung fu or action movie.

In fact, I owe Tower Records for introducing me to perhaps our greatest purveyor of extreme Japanese cinema: the one and only Takashi Miike. In those early Internet days, it was honestly difficult to find information on any Japanese movie that wasn’t called Battle Royale. So imagine my surprise when I wandered through the Foreign Film section at Tower Records and a knowledgeable employee (who I mysterious never saw again) began chatting me up about this director named Miike, whose work was just now finding its way to American shores. I was intrigued by the cover art and descriptions for a bevy of movies that couldn’t have appeared more disparate: the chilling bait-and-switch of Audition, the manga-come-to-life that is Fudoh: The New Generation, and the zombie-comedy-musical Happiness of the Katakuris. Any of those films would have been an ideal starting point for a budding Miike fan, but for some reason my interest was drawn elsewhere.

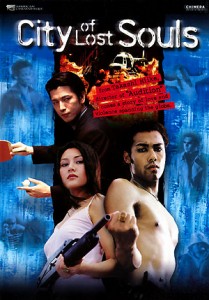

Maybe it was my love of Asian gangster movies; maybe it was the evocative title; or maybe it was the Tower employee assuring me that the film contained the first ever parody of The Matrix’s bullet time. Either way, my introduction to Takashi Miike came with my purchase of City of Lost Souls that afternoon. It’s a Miike effort that is discussed rarely, if ever, these days, but in its own way it worked as a stellar entryway into Miike’s mad, mad world, and in any event, by the time the credits rolled I knew I needed to see more.

On the surface, City of Lost Souls is your standard lovers-on-the-run tale, not so different from the Tarantino-penned True Romance, as the Brazilian-Japanese protagonist Mario and his Chinese girlfriend Kei (played by iconic Nineties Hong Kong actress Michelle Reis) find themselves in the crosshairs of Chinese Triads and Yakuza crime bosses while stranded in a country that would love to see them deported. In Takashi Miike’s hands, however, City of Lost Souls becomes a live-action cartoon, crackling with the kind of manic energy and punk rock attitude that defined the opening ten minutes of his 1999 breakthrough Dead or Alive. Early in the film, we watch as Mario and Kei leap out of a helicopter and land on their feet as unharmed as the Road Runner. Later, the lovers lie asleep in bed as a spider crawls across Kei’s shoulder, only for it seamlessly merge with her skin as a tattoo. I haven’t even mentioned the cockfight where the chickens imitate Keanu Reeves’ gravity-defying kung fu. If it isn’t already clear, we have departed reality and entered Miike land. And it is a terrifying and wonderful place to be.

There’s a touch of social commentary here, as Mario’s heritage speaks to the fact that Brazil is home to the largest population of Japanese outside of Japan, and many of those Japanese have faced discrimination when migrating back to their homeland. That said, City of Lost Souls is not a film concerned with realism –– realism would only get in the way of the fun Miike has in store, like two crime bosses engaging in a deadly game of ping-pong. This is a film defined by Miike’s go-for-broke lunacy, making it an exemplary work of this period of his career, when he was just beginning to carve out a niche for himself away from the Direct-to-Video market.

By selecting both Time & Tide and City of Lost Souls as influential films in my life, it’s obvious to me that my teenage self was most impressed by visual inventiveness and kinetic action. Saying a movie resembles a music video carries something of a stigma these days, but there was a time when filmmakers as diverse as Wong Kar-wai and Takashi Miike were adopting the fluid camera work, surreal lighting, and rapid-fire editing regularly found on MTV in the Nineties, and using it to innovate global cinema. There’s a certain roughness around the edges to City of Lost Souls, and one senses that Miike’s heart may not have been in it the way it was for his more esteemed works, but its devil may care stance and irreverent humor earn it a place in the Miike canon. It’s also one of the few Japanese action movies I can think of that reflects the ethnic diversity of modern Tokyo.

My sense is that City of Lost Souls is not a film that immediately springs to mind when considering the work of Takashi Miike. I myself am actually due for a rewatch –– it’s been years. But there are sequences and moments peppered throughout the movie that have stayed with me in the decade since, and, much like Time & Tide, it was a film that transformed me from casual viewer to full-fledged connoisseur. Little did I know when I plucked City of Lost Souls from the shelves at Tower Records, but I was taking another early step into the world of collecting (and obsessing) over Asian action cinema. Directors like Takashi Miike have ensured it’s been as wild as a helicopter ride with Mario and Kei.

Read Eastern Cherries – First Experiences of Asian Cinema: Japan Edition Part I

Read Eastern Cherries – First Experiences of Asian Cinema: Japan Edition Part II

Read Eastern Cherries – First Experiences of Asian Cinema: Japan Edition Part III

1 Comment