It all comes back to Blockbuster Video. Sure, when you think of the former franchise’s early 2000’s heyday, you might resent them for ordering and taking up so much shelf space with 200 copies of Vin Diesel’s xXx that nobody wanted to rent. But in the midst of all the would-be Hollywood hits and Casper Van Dien Direct-to-DVD flicks, you would occasionally find a foreign film diamond in the rough. Such was the case when I took a chance on the 1999 South Korean action film Shiri, which made its way to North American DVD in early 2002.

It all comes back to Blockbuster Video. Sure, when you think of the former franchise’s early 2000’s heyday, you might resent them for ordering and taking up so much shelf space with 200 copies of Vin Diesel’s xXx that nobody wanted to rent. But in the midst of all the would-be Hollywood hits and Casper Van Dien Direct-to-DVD flicks, you would occasionally find a foreign film diamond in the rough. Such was the case when I took a chance on the 1999 South Korean action film Shiri, which made its way to North American DVD in early 2002.

In a way, it’s almost a marvel that I rented the film at all – much like Miramax’s notoriously awful art for Infernal Affairs in 2004 (boasting a minidress-wearing Shu Qi lookalike who appears nowhere in the film), Sony’s DVD release of Shiri features a misleading cover, in this case a faceless Korean woman holding a pistol in a barely-there dress. Who knows, this blatant attempt at sex appeal may have helped Sony move more units, but it completely mischaracterizes the film for prospective viewers.

Stylish and fast-paced in the Jerry Bruckheimer mold, Shiri is a race-against-the-clock spy actioner modeled after the successful Hollywood blockbusters that came before it, only this time with a tragic romance tossed in for good measure. Even the soundtrack by composer Lee Dong-jun (Save the Green Planet!) shamelessly riffs on Hans Zimmer’s score for The Rock. What gives Shiri its particular flavor is the focus on North Korean and South Korean relations. In what is perhaps it’s most effective sequence, Shiri opens with a montage of North Korean soldiers engaging in some absolutely brutal training, training that involves mercilessly slaughtering nameless captors and even their own comrades. This is our first indication that, despite director Kang Je-kyu’s attempt at mass appeal, Shiri is not a film to shy away from hard-R violence.

For more on misleading DVD covers, click here.

From there, we soon discover the North Koreans have sent their most capable soldier to infiltrate the South and carry out various assassinations and other acts of espionage. Leading man Han Suk-kyu and a very young-looking Song Kang-ho are the two South Korean government agents on the case. If you don’t think the spy’s identity will be revealed in a surprise twist involving Han Suk-kyu’s fiancé (played by Lost’s Yunjim Kim), then you may want to pay closer attention. It’s worth mentioning that Yunjim Kim’s handler is played by Choi Min-sik, just a scant four years before he became the Oldboy we know and love.

Watching Shiri in 2018 is an almost quaint experience. The film wears its Hollywood influences on its sleeve, playing out like a remix and reworked version of James Cameron and Michael Bay’s greatest hits. There’s the military themes and emotive music of Bay’s aforementioned The Rock, while Han Suk-kyu’s attempts to keep his secret agent day job a secret from his fiancé recall Cameron’s True Lies. Unfortunately, the action sequences – often a highlight of Korean genre cinema – are far cry from the elegance and intricacy of a Cameron setpiece. While the North American DVD claims to be in 1.85:1 widescreen, the tight camera angles and shaky handheld photography during shootouts frequently made me feel like I was watching something shrunk down to a 4:3 aspect ratio. The action scenes here feel positively claustrophobic as a result, and spatial geography quickly goes out the window, as during a kitchen gun battle in which Choi Min-sik seems to have turned on some kind of video game cheat code so that he never runs out of bullets.

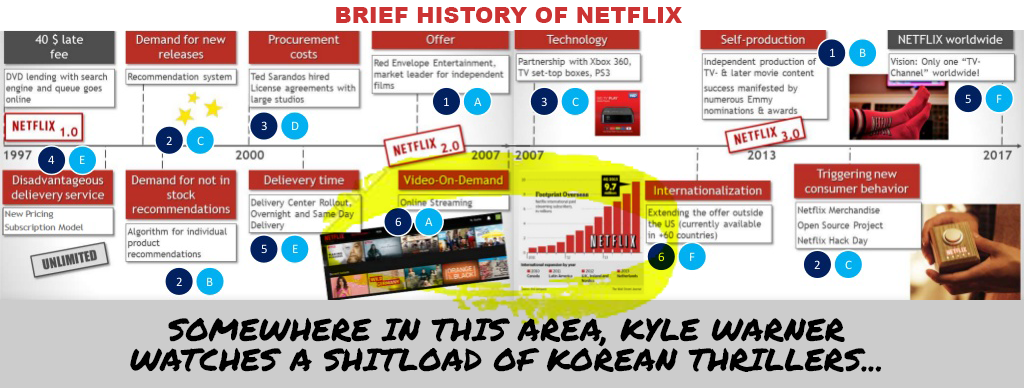

The DVD’s Special Features include a behind-the-scenes documentary that I think really underscores what a film like Shiri represents circa 2018. Throughout the doc, both newscasters and members of the production team express their hope that Shiri’s success will pave the way for more Korean films to perform well at the domestic box office. Clearly, this is a wish that has come to fruition, as just a few short years after the colossal success of Shiri (it outgrossed Titanic from, you guessed it, James Cameron), Korean cinema begin to flourish with the numerous titles we now regard as modern classics, from Memories of Murder to A Bittersweet Life and beyond. It’s oddly touching to look back and realize that, only twenty years ago, a movie like Shiri – with a budget of $5 million dollars, considered massive at that time – was seen as a gamble in South Korea. In other words: you’ve come a long way, baby.

I doubt anyone would make the case that Shiri is a great movie, or at least not a “great” movie in the same way Oldboy is, but it does prove well-acted, the production values are slick, and the storyline hits the right notes of tragedy by its denouement. The real-life stakes of North and South Korean relations also lend the film a particular gravitas it would not otherwise have as just another spy vs. spy tale. Its influence in that regard can still be felt in recent North-meets-South flicks like Confidential Assignment and Netflix’s Steel Rain. But these days Shiri is arguably most interesting as a time capsule, a snapshot of the last moment before the Korean Wave took hold and transformed the country into what many cinema fans, myself included, consider to be most exciting film industry in the world today.

Read First Experiences of Asian Cinema: Korea Edition Part I

Read First Experiences of Asian Cinema: Korea Edition Part II

Read First Experiences of Asian Cinema: Korea Edition Part III

While I can definitively say that Jackie Chan introduced me to Hong Kong/Chinese cinema and that

While I can definitively say that Jackie Chan introduced me to Hong Kong/Chinese cinema and that

2 Comments