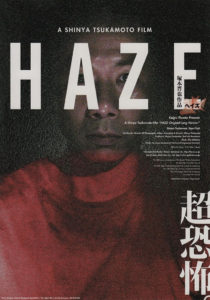

Director: Shinya Tsukamoto

Cast: Shinya Tsukamoto, Takahiro Murase, Takahiro Kandaka, Masato Tsujioka, Mao Saito

Running Time: 49 min.

By Henry McKeand

Shinya Tsukamoto’s films have always presented a claustrophobic view of the world. Even in massive and open urban landscapes, Tsukamoto’s characters are trapped by the oppressive man-made structures that surround them. There’s the sense that concrete and steel are capable of closing in at any time, overwhelming and overpowering helpless human bodies.

It’s fitting, then, that Tsukamoto would explore an aggressively literal version of this claustrophobia with 2005’s Haze, which centers on a man trapped in an uncaring concrete maze. Initially screened as one of the digital short films of the 2005 Jeonju International Film Festival in Korea, Haze is Tsukamoto at his most uncompromising.

The plot seems simple at first. A man (played by Tsukamoto himself) wakes up in a cramped, dark space with no real recollection of how he got there. With his back against the floor, his nose is an inch away from a massive concrete ceiling. He can barely turn his head, let alone find his way out. It’s a jarring first scene that expertly captures the despair of the situation. Tsukamoto has long been one of cinema’s most tactile filmmakers, and he gives every harsh slab of cement a gritty texture that’s uncomfortable even to watch. As a performer, he desperately crawls and twists his body, underscoring just how terrifying the situation would be.

What follows is a sequence of dread-inducing, breathe-through-your-nose setpieces. The highlight has Tsukamoto biting down on a stretch of thick pipe in a dangerously narrow hallway. His only way out is to move down the hallway, but he doesn’t have enough room to remove the pipe from between his jaws. The sound of his teeth scraping against the metal is painful, resulting in a scene that feels nightmarish in the truest sense of the word.

Throughout this torment, the man wonders what led to his imprisonment. Was he on the wrong side of a war and taken prisoner? Or is a rich sadist torturing him for amusement? Presented with the unflinching brutality of his situation, the answer seems almost unimportant. Movies are rarely so immediate; because the protagonist can’t see more than a few inches ahead, the film itself is concerned with the here and now. For most of the 49 minute runtime, all that matters are the bumps and spikes and rough edges of the maze. And while it’s a short film, it feels like a comprehensive journey into one man’s personal hell. Anything longer could have been overkill.

Eventually, the man does run into someone else: a determined woman who seems equally confused about their situation. As the two of them talk, the movie becomes more contemplative. The physical torments they experience begin to feel like manifestations of emotional anguish. Even in his most blunt force work, Tsukamoto never explicitly spells out his themes, and Haze’s ambiguity has a haunting and unsettling effect. The final ten minutes are surprisingly human and tender for a film as cruel as this one, proving that Tsukamoto is interested in more than pure torture.

In regards to torture, many have written about Haze as Tsukamoto’s answer to films such as Saw. And while it has a similar industrial nastiness to Saw and the subgenre it inspired, it would be a mistake to view the film as a mere response to contemporary trends. Tsukamoto was exploring the fragility of the human body long before the so-called “torture porn” wave, and Haze’s dirty and cold look is a natural evolution of his earlier work with Tetsuo and Tokyo Fist. Haze does feature a significant level of gore, but the viscera itself is less important than the way it contributes to the protagonist’s dehumanized mindset.

There’s another key distinction between Haze and Saw. Saw’s humanism derives from the idea that the traps and torture rooms are literal and the victims would be able to appreciate normal life more if they were to escape. Haze, on the other hand, offers a more complicated view. Tsukamoto seems to be suggesting that modern life is so brutalizing that the only way to truly escape is to reach a kind of mental peace. The maze is terrifying, but the outside world of skyscrapers and bombs isn’t much better.

Some will appreciate the thoughtful second half, while others will see it as a letdown after the relentless opening. Regardless, the filmmaking itself is astounding. Shot on early digital cameras, Haze is a low-budget and ugly movie dominated by murky dark colors, but every shot is deliberate and thrilling. Tsukamoto uses extreme close-up to create the illusion of scope; the corridors are rarely shown in full, but the claustrophobic, disorienting direction forces the viewer to imagine a maze more horrifying than any big-budget film set. Tsukamoto’s ingenuity and imagination turn a barebones concept into a short film that’s Lovecraftian in its excitement and epic implications.

Henry McKeand’s Rating: 8/10