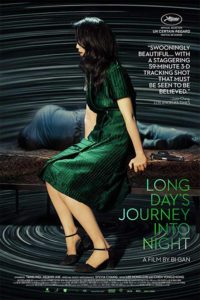

Director: Bi Gan

Cast: Tang Wei, Huang Jue, Sylvia Chang, Lee Hong-chi, Chloe Maayan, Ming Dao, Xie Li-Xun

Running Time: 138 min.

By Paul Bramhall

Once in a while a movie comes along that transcends genres and conventions, the type of movie that lingers in the mind long after the credits have rolled, and results in many a late-night conversation. Movies like Lee Chang-dong’s Burning and Takeshi Kitano’s Hana-Bi both fit the bill, and joining their esteemed company is Bi Gan’s A Long Day’s Journey Into Night.

Much like Korean director Yoo Ha, Gan is a poet turned filmmaker, and displays the rare ability to transpose that poetic tone to film, crafting a hallucinogenic noir that has distant echoes of Wong Kar Wai and David Lynch. A Long Day’s Journey Into Night is Gan’s sophomore full length feature, and in it Huang Jue (The Final Master, The Wild Goose Lake) plays a former casino manager who returns to his hometown after his father passes away, visiting his stepmother who’s now been left to run the family restaurant named after his birth mother. While there, he discovers a photo of an old flame in the back of a broken clock, and soon finds himself attempting to find out what became of her through a mix of unreliable nostalgia and fragmented memories.

The woman of his memories is played by Tang Wei (Lust, Caution, Wu Xia). Remembered in a distinctive green dress, their love affair played out against the backdrop of her being involved with the local gangster, who murdered Jue’s close friend. Having returned to the town after so many years, most of these characters have long since disappeared. The gangster went on the run, or perhaps was killed himself, Wei simply vanished, with the only connection left being the mother of Jue’s murdered friend, played by the legendary Sylvia Chang (of the Aces Go Places series, Eight Taels of Gold).

While the plot itself may not bring anything profoundly new to the table, the concept of a man returning to his hometown and looking for an old flame has been done plenty of times before (most notably for me in Im Kwon-taek’s 1976 production A Byegone Romance), the plot itself here is largely peripheral. Gan is more interested in exploring the reliability of our memories, and how much we add meaning to them based on fleeting moments in time. The hometown that Jue returns to, portrayed by Gan’s real hometown of the rarely seen Guizhou in southwest China, has a somewhat decaying feel to it. Buildings and structures seem rundown and falling into disrepair, and as an audience we follow Jue as he re-visits his old haunts, each one triggering a memory of what transpired all those years ago.

Gan creates a deliberate pace, echoing the likes of similar contemporary Chinese cinema like Diao Yinan’s Black Coal, Thin Ice and Jia Zhang-Ke’s Ash is Purest White, that draws you into the characters journey. With each lead Jue stumbles across its impossible to tell whether it’ll draw him closer to discovering what became of Wei, or if he’s simply clutching at straws born out of a sudden obsessive need to find her again. Just as we’re settling into the melancholic rhythm of Jue’s detective like attempts to locate his former lover, A Long Day’s Journey Into Night completely flips the narrative on its head. Visiting a cinema to watch a 3D movie he drifts into sleep, the result of which is arguably a pièce de résistance of modern cinema, as the narrative segues into an hour long one-take 3D dream sequence.

Taking up the entirety of the latter half, while it would easily be possible to spend the rest of the review espousing the technical tenacity to pull off such a shot – it’s a real one-take, not stitched together in post-production – the real achievement is the meaning it carries. A mesmerising and surreal journey, Gan creates what’s probably the closest we’ll get to the feeling of a dream being captured on film. While there’s nothing particularly different from the realism of the surroundings Jue finds himself in compared to his waking life, there are just enough odd moments that indicate a displacement from reality.

Running towards the entrance of a disused mine at the top of a hillside village, he’s unable to remember how to get back to the bottom of it, and the girl he’s looking for is no longer portrayed by Wei, instead represented by a forlorn and distant kareoke singer. When he enquires to if she’ll be singing that evening, it’s confirmed she will be, but also that the already worn down establishment she’ll be singing in will be torn down the following morning. Exactly where Jue is and what the significance is of each character he meets is never implicitly stated, instead the sequence acting almost as a counterpoint to the first half, pondering the question of how much reality is reflected in a dream compared to what our memories tell us.

Similar to Tsui Hark director Gan shows an implicit understanding of how powerful 3D can be when used creatively. There’s nothing flying towards the screen here, instead the technology being used to create layers of depth absent from the 2D first half set in the present. Gan himself put it best in an interview, explaining that ”When you close your eyes and remember, you almost seem to see it in a very three-dimensional way, even though it’s something recalled from the past, something that’s already happened I feel that when you open your eyes and you’re back into this world and the present, that 3D was the best way to capture the sensation of the difference between memory and existing in the present.” The end product meets Gan’s vision admirably, with A Long Day’s Journey Into Night easily being one of the best examples of how cinema as a visual medium can be an immersive experience for the audience watching.

The town of Guizhou itself feels as much of a character in the narrative as the actors, a location barely seen on film before Gan took it on himself to use his hometown as his movies backdrop. The cinematography paints a town full of rust, crumbling buildings, and rippling puddles, one which almost seems to insist Jue gives up on his search even before he’s started it. Perhaps that’s why the Guizhou that appears in his dream seems to make more sense than the reality he’s in. While the surroundings are no less dilapidated, there’s a progression to his journey, with steps and alleyways leading to interactions and stolen moments that indicate a sense of importance that’s just out of reach.

It would be a crime not to mention the soundtrack. While the Vengaboys deserve an award for the most unexpected appearance in a movie this side of 2000, most memorable is the usage of traditional singing by the Miao and Dong minorities from the region. Their distinctive singing has been mixed to create an almost chant like sound, not dissimilar to what you’d hear in a Buddhist temple, and the result is a feel that adds an otherworldly ambiance to parts of the dream sequence.

Gan himself was the relatively youthful age of 30 when he made A Long Day’s Journey Into Night, with his debut full length feature coming in the form of the equally mesmerising Kali Blues from 2015. A rare talent armed with an acute insight into the human psyche, his work feels like it takes those thoughts that can blinside us at 3:00am, and use cinema to turn them into narratives that capture their exact essence. At one point Jue poses the question ”Do we know when we are dreaming?” via voiceover, a question aimed at us as the viewer as much as it is at himself, and one you’ll be left pondering long after the credits have rolled. While some may find the lack of traditional structure and definitive conclusion a frustration, for those willing to be taken on the journey, A Long Day’s Journey Into Night is a rewarding experience quite unlike any other.

Paul Bramhall’s Rating: 9/10

I’ve been hearing a lot of talk with this film, and it sounds like it’s warranted. I feel like I’ll only be able to immerse myself in it if I’m watching it alone at night with no interruptions.

This movie has been on my list for a while. Very surprised (and also appreciative!) to load up this website and suddenly find a review on it from Mr. Bramhall himself.

My introduction to Bi Gan was 2015’s “Kaili Blues”. I’m not typically a fan of arthouse movies, but the snippets of reviews and murmurs surrounding the movie ultimately ended up drawing me in. I decided to go into it with an open mind, not expecting a traditional movie plot; but rather, just a raw “experience”. I really enjoyed it this way. It also helps that the film was absolutely gorgeous.

I feel like I should seek out more Chinese independent/arthouse movies. Years ago I remember seeing a post on Reddit that compared the most popular Google search terms from various parts of the world. Whereas the search terms from western nations were typically average day-to-day questions about money, relationships, and and tech, Chinese Google searches were far more existential. “Why does the sun rise?”, “What is our purpose?”, etc, etc. I suspect Asian culture might be the most existential and introspective culture in the world, and a lot of that ends up manifesting in their cinema. (Or at least, their indie cinema. Big budget propaganda aside.)

I have the blu-ray for “A Long Day’s Journey Into Night”. My only regret is that I don’t have a 3D TV to watch it on, and that production on new 3D TV sets basically went the way of the dodo after 2016. Fortunately I’ve managed to figure out how to watch 3D movies on my virtual reality headset, but the experience just isn’t quite the same. If I can’t befriend someone with a proper 3D TV then I may just go the VR route.

The hour-long continuous camera take sounds like a major technical feat, and of course I want to watch the movie the way it was intended to be viewed.

Let us know how your search for 3D equipped friendship goes Dan! 😛 As always, look forward to hearing your thoughts once you’ve had an opportunity to check it out.

I think that Reddit post has stitched you up though, Google is blocked in China!

Drat. The internet has lied to me again! (In hindsight, those stats may have actually come from Hong Kong, not China.)