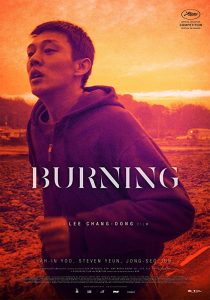

Director: Lee Chang-Dong

Cast: Yoo Ah-In, Steven Yeun, Jun Jong-Seo, Kim Soo-Kyung, Choi Seung-Ho, Moon Sung-Geun, Min Bok-Gi, Ban Hye-Ra, Lee Bong-Ryun, Lee Young-Suk

Running Time: 148 min.

By Paul Bramhall

It’s been 8 years since Lee Chang-dong last sat in the director’s chair, having helmed 2009’s critically acclaimed Poetry, leaving it just long enough for the rest of us to worry if we’d ever see a Lee Chang-dong movie again. With the benefit of hindsight, we now know he was one of the many names on impeached former president Park Geun-hye’s entertainment and media blacklist, which refused state funding to anyone who was seen as a critic of her policies (notably Park Chan-wook was also named). Thankfully in 2018 Chang-dong came out of his hiatus, and returned to the big screen with Burning, an adaptation of a Haruki Murakami short story titled Barn Burning.

The story appeared in Murakami’s shorty story omnibus The Elephant Vanishes, and marks the third time for one of its tales to be transferred to the screen. In 1982 Naoto Yamakawa directed Attack on the Bakery, from the short story of the same name, and a year later he’d also adapt On Seeing the 100% Perfect Girl. Both where (perhaps fittingly) short films, so Burning is both unique from the perspective of it being a Korean director taking on the Japanese authors source material, and that it’s been expanded to encompass a 2 & ½ hour epic.

The story casts Yoo Ah-in (Veteran) as an aspiring writer, who takes on various menial jobs as a source of income. In the opening scene we’re introduced to him delivering stock to an outlet store, and by chance he meets a childhood friend who’s working as a promotional model outside the store. Played by newcomer Jeon Jong-seo, the pair agree to catch up over drinks and reminisce about their time growing up in the countryside. Jong-seo reveals she plans to travel to Africa, and how she wants to visit the tribes that live in the Kalahari Desert. She enthusiastically explains how the tribes have two expressions related to hunger – Little Hunger refers to those who are hungry to eat, and Great Hunger refers to those who have a hunger to understand the meaning of life. Before Ah-in knows what’s hit him, he and Jeong-seo are in bed together in her small unit, and he agrees to keep her mysteriously unseen cat fed while she’s travelling.

After Ah-in receives a call from Jeong-seo in Kenya to say she’s coming back to Korea, he agrees to pick her up from the airport, however is visibly taken aback to find she’s joined by a male acquaintance, played by Steven Yuen (Okja). Yuen explains they became close during a long delay in the airport, as they were “the only two Koreans”, but something seems off about him. He’s hesitant to divulge what he does for a living, but is clearly rich enough that he drives a Porsche, lives in the affluent Seoul suburb of Gangnam, and his spacious apartment is adorned with expensive looking artwork. Ah-in makes a comment comparing him to the Great Gatsby, but Yuen’s silky smooth performance feels more pointed towards Patrick Bateman.

The relationship between the trio is essentially the crux of Burning, and each one of their perceptions of the other. More so than any of his previous movies, Chang-dong’s latest could well be described as baffling for the unacquainted viewer. Scenes which feel meandering and uneventful at the time, become rife with questions in retrospect, and seemingly inconsequential pieces of dialogue seek to be re-evaluated once mulled upon. Burning is the kind of movie which practically demands a 2nd viewing, and then a 3rd, because so much is unseen that it feels impossible to comprehend all of the nuances on the initial experience. While Chang-dong eschews a traditional narrative for his latest, the frequently uncomfortable levels of tension come from trying to figure out how much of what’s being implied is real, and how much is being imagined, as much from ourselves as from the perspective of the character’s we’re watching.

Yuen’s performance is a revelation. This marks the first time for him to take a lead role in a Korean production, after supporting parts in 2017’s Okja and 2015’s Like A French Film, and while he remains most well-known for his role in the U.S. series The Walking Dead, roles like this one show a previously unseen range. Despite his fluent Korean, there’s something distinctly alien about his presence, from small details such as his character not using a Korean name (he calls himself Ben), to strange asides about how he considers his meal preparation as a form of making offerings to himself. All signs point to him being a sociopath, but Chang-dong’s direction insists on keeping the audience at arms-length. It’s a tactic which results in proceedings feeling frustratingly opaque, but also impossible to turn away from, often both at the same time.

Newcomer Jeon Jong-seo likewise delivers a top tier performance in her debut, and at the time of writing has already been tapped as the lead for The Bad Batch director Ana Lily Amirpour’s next feature, titled Mona Lisa and the Blood Moon. She takes center stage during Burning’s pivotal scene, which sees the trio converging in the yard of Ah-in’s countryside home, close to the border of North Korea. They share a joint, and in a surreal but beautifully filmed sequence she dances topless around the garden, imitating the Great Hunger dance she spoke of earlier. The fire the Kalahari Bushmen danced around as the sun set on the horizon is now replaced with the mountains of North Korea, the propaganda from the loud speakers a constant presence in the background, and for a moment Ah-in and Yuen sit there transfixed.

The concept of fire carries significance for each of the three main characters, with the joint lowering Ah-in’s defences enough that he reveals a traumatic memory from his past, while Yuen discloses his “hobby” of burning down derelict greenhouses. After the scene finishes Burning plunges down the rabbit hole, however does so with such subtlety that it’s easy not to notice. Yuen and Jong-seo drive off together back to Seoul, but Jong-seo simply disappears and becomes uncontactable. Yuen confesses to Ah-in that he only visited to scout for empty greenhouses, and assures him to keep an eye out for one close-by being burnt down in the next few days, but it never happens. Then of course there’s the cat that was never actually seen, despite the food Ah-in left out for it being eaten, and its droppings being left in the litter tray.

Just like the difference between the Little Hunger and the Great Hunger, there’s an impression that Chang-dong is applying the same principle to the audience. Are we caught up in trying to solve all of the little mysteries that are weaved into the narrative, or are we looking at the bigger picture as to what exactly they all mean? Much like Bong Joon-ho’s Parasite, Chang-dong’s latest has its lens pointed at the class divides that exist in Korea, and the injustices, both perceived and imagined, that stem from them. The anger and rage that are born out of these divides is evident in both, however in Burning that seething energy always feels like its hovering just beyond the borders of the screen. Ah-in feels that something is amiss with Yuen’s interest in both him and Jong-seo, but he can’t articulate it, and perhaps none of us can.

By the time the end credits roll, the sense of danger that’s remained so elusive to pinpoint has neither dissipated nor been resolved, but rather manifested itself as a feeling that prompts bigger questions, which is perhaps the whole point all along. At one point Ah-in states that the world is a mystery to him, and uses this to offload the blame for the fact he hasn’t been able to write anything. The mysteries of the world mean it’s often not that simple to have a beginning, a middle, and an end, and that lack of narrative structure is also applied by Chang-dong with the way the narrative unfolds.

Burning has already earned the accolade of being the highest rated movie in the history of Screen International’s Cannes jury grid, and is also the first Korean production to make the final shortlist for the Academy Awards Best Foreign Language Film category, recognition which is well deserved. When Ah-in and Jong-seo first meet she perfectly pantomime’s peeling and eating a tangerine, telling him that if he ever wants something, he can create it by doing the same. Just like the tangerine, Burning feels like its equal parts character drama, mystery thriller, and misguided romance, but it could just as easily be none of those. A perplexing epic that poses a lot of questions, and expects the audience to find its own answers, Burning is a triumph.

Paul Bramhall’s Rating: 8.5/10

Loved it – so many ambiguities that just lead you on a different path with each watch. Jong Seo’s explanation on the art of pantomiming – a great analogy of whats to come. Lee Chang-Dong’s direction is incredible. A slow “burn” with an ending that can either leave a sour taste or sweet satisfaction. Steven Yuen asking Ah-in to explain what the meaning of a metaphor is is pure bliss.

Great review Paul, covered all the bases.

Read online that Greenhouse is slang for plastic girls in Korea – would you know any more about this?