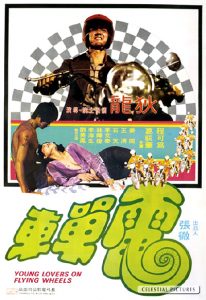

AKA: The Motorcycle

Director: Ti Lung

Cast: Ti Lung, Ching Hoh Wai, Got Dik Wa, Dean Shek Tien, Lee Man Tai, Lam Fai Wong, Gam Gwan, Lee Hoi San, Chiang Nan, Lo Wai, Wu Ma, John Woo

Running Time: 99 min.

By Matthew Le-feuvre

Although, in part, influenced by the ‘biker’ B-flicks of 60’s Americana. This interesting ‘variation on the theme’ was a radical departure for matinee idol, Ti Lung; whose ‘then’ career had been proliferous under Chang Cheh’s mighty guardianship before moving on to collaborate with the analogous likes of Sun Chung, Lo Chen and Tang Chia. Here, this inclusion to Lung’s (already) hulking filmography – bar exception his anaemic cameo in The Generation Gap (1973) as well as the erstwhile, long overlooked Dead End (1969), was more or less engineered to be an urban commentary on 70’s materialism; in this case, a Suzuki motorcycle and the accompanying social status that comes with owning one.

In a change from the habitual slew of wuxia theatre or the empty hand dynamics of The Savage Five or They Call Him Mr. Shatter (both, also 1974), Lung dutifully and creatively appropriates duel responsibilities of leading man/director for what tentatively appears to be an endearing essay about the fundemental standards of ‘life decisions’ and the ‘maturity’ to effectuate the importance of emotional growth over conceited ambition or needless ‘materialistic’ philosophies: being the “best” or possessing the “best” does not necessarily conjure limitless happiness or contentment. In fact, it can also (un)intentionally draw its opposites – society being superfluous with ‘hungry wolves’, ever prowling for opportunity, hoping too inherit the slightest fraction of the top dog’s mantle.

While this is a minor aspect of I Keung’s bulky, if not frenetic screenplay, Lung is certainly assiduous in tackling these contemporary issues and situational ingredients which; for the sake of external padding, emerge in frequency to the point of ridiculousness, I.e, Loan sharks who (instead of regular re-payments) want to peddle Lung’s rare blood type to two inept thieves played with moronic abandon by stalwarts: Li Hoi San and the over gesticulative Dean Shek, toppled by the contrived inclusion of a potential father-in-law who abhors bikes of any description, involuntarily morphes into a dramatic impediment rather than anchoring audiences into states of empathy,

Lest do we ignore that these mushrooming subplots and emotionally bloated diversions actually smokescreens the essential crux about an office clerk’s singular passion (or obsession?!) for motorcycles. Yet, from a psychological perspective, this hehaviour would be a typical catagorization for a neo-freudian where the bike itself becomes a symbolic extension of the character’s (Song Da/Lung) manhood; whilst in concurrent terms his zealous need for ownership via unorthodox means (entering a kung fu tournament) subtly represents/conceals an inability to interact with society and relationships in general, particularly from the picture’s opening shots of Song Da/Lung rejecting his girlfriend’s amourous advances to ensueing sequences where he’s virtually hypnotized outside a dealership showroom.

As per usual, Lung is worthy of acclamation, combining social naivety with forceful resolve for a performance, which, although supported by a consistent flux of balletic altercations – courtesy of Liu Chia Liang/Lau Kar Wing’s toned-down action arrangements, undividedly showcases a very complex, not necessarily ‘heroic’ character who is basically a ‘victim of circumstance’ despite being (A): one-dimensional in his thinking, (B): competitive the next to (C); a complete egotist governed by his own maxims until external factors truly challenge him both in combat and reponsively. Thus birthing an optimistic conclusion.

In a profound way, one could assert that the characteristic nuances of Song Da/Lung are to some extent almost a physical epitomization of the late Robert South’s philosophical/psychological observance on “possessions”:

“In all worldly things that man pursues with the greatest eagerness and intention of mind, he finds not half the pleasure in the actual possession of them as he proposed to himself in expectation”.

Verdict: By no means a memorable or essential Shaw Brothers classic. Still, regardless of “too many situations” that tends to ricochet from urbanized drama to replicative incongruity, when viewed today, Ti Lung’s proficient direction and usage of familiar locations/stock players; contrarily, adds a touch of nostalgic charm as well as a sense of irony to an otherwise pretentious excursion into mediocrity.

Watch out for an extremely youthful John Woo in an unflattering cameo, sobbing at a police reclamation vehicle depot. Needless too say, twelve years later, woo would rescue Lung’s declining career by casting him as one of the triumvirate leads for his pioneering gangster epic: A Better Tomorrow (1986).

Matthew Le-feuvre’s Rating: 7/10

OMG …. Who needs Easy Rider?

Released in the USA with the rather uncommercial tagline “For Ti Lung completists only!” .. Hehe.

Just watching the trailer, I do rather like that shot of them riding that bike through the ocean. Maybe John Woo was weeping becuase they got to such an exquisite piece of Ti Lung slowmo before him?