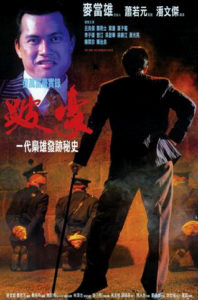

Director: Poon Man-Kit

Writer: Johnny Mak

Cast: Ray Lui, Cecilia Yip, Kent Cheng, Waise Lee, Amy Yip Chi May, Frankie Chin, Elvis Tsui, Tommy Wong, Kenneth Tsang, Lo Lieh, Paul Chu Kong, Mark Houghton

Running Time: 136 min

By Paul Bramhall

The tale of real life gangster Ng Sik-Ho, more commonly known as Crippled Ho, has experienced a resurgence of late thanks to Donnie Yen’s take on the character in 2017’s Chasing the Dragon. Much of the talk around Ho’s latest incarnation, was how it skilfully frames the story so as to massage it through the Mainland China censorship board, which takes a hard line on any movie perceived as glorifying a criminal lifestyle. While Wong Jing’s (and his small army of co-writers and directors) effort is an admirable one, there was more than one occasion on watching Chasing the Dragon, when I found myself thinking how much better it could have been without all the subtle political narrative manoeuvring. Thankfully, such a version exists, and it comes in the form of Poon Man-Kit’s 1991 epic To Be Number One.

Unlike Chasing the Dragon, which gave equal focus to Crippled Ho and corrupt cop Lee Rock, To Be Number One is a pure gangster tale, and all the better for it. Although on a side note, in the same year Lee Rock would also be the focus of 2 movies, the self-titled Lee Rock and its sequel. Clocking in at 135 minutes, To Be Number One is unlike any other Hong Kong movie of the era in terms of its scope and ambition, anchored by a powerhouse performance from Ray Lui as the titular character (so yes, if you want to see Crippled Ho 1991 vs Crippled Ho 2017, check out Flash Point). Made at a time when Hong Kong cinema was very much in its prime, Lui’s take on Crippled Ho was just one of nine movies he’d feature in during the same year. Interestingly he’d play Crippled Ho twice, turning up for a second time in the Amy Yip (who’s also in To Be Number One) vehicle Queen of Underworld.

While all of the subtitled releases of To Be Number One unfortunately neglect to translate the large swathes of text that intermittently appear onscreen, indicative of the passing of time and significant events of the era, luckily this oversight doesn’t prove to be detrimental to the viewers enjoyment. Man-Kit, who up until this point had cut his teeth directing gritty slices of HK Triad life such as Hero of Tomorrow and City Kids 1989, brought in a whole host of top shelf talent to bring his vision to life. Respected cinematographer Peter Pau, who would go onto lens the likes of The Bride with White Hair and Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon, here shows early signs of his unique eye for framing a scene, working from a script by Long Arm of the Law director Johnny Mak and Stephen Shiu.

Several reviews out there make comparisons to Brian De Palma’s Scarface, and structurally it’s a fair comparison. As a country bumpkin from the Mainland (remember when Mainlanders where always portrayed as country bumpkins in HK cinema?), Lui arrives in Hong Kong in the 70’s to escape the Cultural Revolution. While he and his friends find themselves slumming it as coolies in a rundown restaurant, they also work odd jobs that toe the line between legal and criminal, one of which eventually puts Lui on the radar of a powerful HK gang boss (played by Kent Cheng), who sees potential in his ambitious personality. Soon finding himself moving up the ranks within the gang’s well-oiled drug trade, Lui’s goals gradually begin to expand beyond the lot he’s been given, and the lust for power leads to a bloody war between the pair that stretches across the next 2 decades.

It’s a structure that’s proved to be tried and tested over the years, with the likes of Martin Scorsese’s Goodfellas and Yoon Jong-bin’s Nameless Gangster also adhering to the same framework. One aspect that they all have in common though, is that they never feel derivative of De Palma’s classic, and Man-Kit crafts a tale that’s distinctly Hong Kong in its identity. Of course another aspect of any Hong Kong production from the 80’s and early 90’s that deals with the Triads, is the action. It should be made clear that To Be Number One isn’t an action movie, but during this era in Hong Kong action was such an intrinsic part of its film industry, you could expect at least a couple of stunts or fists to be thrown even in the most unexpected genres.

Here Bloodmoon director Tony Leung Siu-Hung is on action choreography duties, and he does an outstanding job of adapting the classical style of his early career (Tiger of the Northland, A Fistful of Talons) to a more contemporary and realistic setting. I’ve always found Siu-Hung’s late 80’s/early 90’s work on triad potboilers to be underrated. He was one of the few action directors who showed a real understanding of how to still keep the hard hitting aesthetic and flow that’s synonymous with HK choreography, but apply it in the context of a more realistic environment. His work on the likes of Walk on Fire and Rebel from China are also stellar examples. Here the action is frequently bloody and brutal, with lime and acid thrown into people’s faces, brutal beatdowns, and even some flying kicks are sprinkled in for good measure, without ever coming across as gratuitous.

Lui’s rise to power is complimented by a fantastic cast of supporting characters. Just like any movie is a product of its time, so it could be said reviews also offer a unique perspective from the time they’re written. Watching To Be Number One in 2018, there’s an undeniable nostalgia to seeing so much talent from Hong Kong’s golden era onscreen together. Waise Lee, Lawrence Ng Kai-Wah, and bulked up bodybuilders Frankie Chan and Dickens Chan (ironically playing brothers) feature as Lui’s fellow Mainlanders and eventual followers. We have Elvis Tsui as a mute enforcer, who at one point gets to go John Woo with some double handed pistol action, and Cat III icon Amy Yip as Kent Cheng’s moll (both Tsui and Yip would star together in the legendary Sex and Zen in the same year). Throw in appearances from Lo Lieh as a gangster and Cecilia Yip as Lui’s better half, you’re left with a cast that can never be replicated.

Any tale that focuses on Crippled Ho eventually culminates in the ICAC’s (Independent Commission Against Corruption) purge against corrupt members of the police force, one which saw Ho’s network of cops that he had in his pocket fall apart around him. While these days the ICAC is more known as the subject of David Lam’s limp wristed Z/S/L Storm series (not to mention 1993’s First Shot – I guess Lam is an ICAC fanboy, if such a thing exists), in To Be Number One the weight of their crackdown is fully felt, as Lui finds himself in increasingly desperate circumstances. Blinded by his own greed and embattled by other rival gangster factions, the added pressure of having to deal with a police force no longer possible to brush off with stacks of cash, all culminate to show just how fragile it is when indeed, you’re number one.

Despite being an early entry in Man-Kit’s filmography, he’d never top the quality on display in To Be Number One. Perhaps too eager to replicate its success, he pulled together an almost identical cast and crew for the sprawling Lord of East China Sea and its sequel in 1993, which saw Lui step into the shoes of Luk Yu-San, a Shanghai fruit seller who rose to prominence as an opium dealer in the early 20th Century. He’d then cast Lui again in Hero of Hong Kong 1949, also from 1993, for another tale inspired by true life events, with equally uninspiring results. It’s proof that even if you have the same chef and the same ingredients, success is not always a guarantee. But in the case of To Be Number One, everything was left to simmer for just the right amount of time and in the right portions, resulting in a satisfying tale of true life crime.

While Chasing the Dragon did its part to prove it’s still possible to tell these tales in today’s SARFT friendly environment, watching Man-Kit’s magnum opus makes you realise just how many sacrifices have to be made in order to do so. While many would say they were worth it, watched against a movie like To Be Number One, there can be no denying, any other attempt could only be a distant number two.

Paul Bramhall’s Rating: 7.5/10

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=q8PyjJ1rKlI

As soon as I saw a few shots in the trailer just now, I wondered if it may have been shot by Peter Pau … The long-lens photography looks gorgeous.

Some good points raised here about Leung Siu Hung’s smashing action, can’t give this oftentimes underrated brother enough props!

I think these days, were China’s film, tv and media watchdog – its actually the SAPPRFT now, Paul, reassigned to the party’s Central Propaganda Department since last spring – is tightly supervising anything that smells like glorification of crime and ruses like the ones Johnny To came up with to make DRUG WAR Mainland-screenable won’t possibly work any more, films like TO BE NUMBER 1 should be seen again, revalued and compared to the sanitized fare that’s doled out today.

Yes, if you’re well-read in Chinese crime history then you know that they also did take an incredible amount of liberties in the script back then, but compared to the characterisation of Ng Sik-Ho in CHASING THE DRAGON Poon Man Kit’s epic almost feels like an HBO documentary.

SAPPRFT – sounds very similar to the noise I make after watching most Mainland flicks these days. 😛 I remember reading about the switch to the Central Propaganda Department (it also came up in the ‘Master Z’ review comments), and you make a really good point that the strategy used for ‘Drug War’ likely wouldn’t work under the tightened restrictions. I’m glad we’ll always have movies like ‘To Be Number One’ to enjoy, as they capture a time in HK cinema that we’ll never get back.

Wow. I first heard of this movie years ago from hkfilm.net which gave the movie a 2 out of 10. I thought Chasing the Dragon was supposed to be the “improved” version based on other people’s perspective.

What really hits home for me in this review is “While Chasing the Dragon did its part to prove it’s still possible to tell these tales in today’s SARFT friendly environment, watching Man-Kit’s magnum opus makes you realise just how many sacrifices have to be made in order to do so.”

I get annoyed when people say modern Chinese cinema is dead, but it’s true that they just don’t make them like this anymore.

I’ll adjust that last line – they

just don’tcan’t make them like this anymore. Sad but true, the restrictions Chinese cinema now have to adhere to mean that movies like this are a thing of the past. I’d be interested to hear your take on it when you have the chance to check it out!Great review Paul, keep em’ coming, after almost thirty year’s, To Be Number One, is still one of the definitive Asian gangsters films.

I don’t think anyone says Chinese cinema is dead, HK cinema however, is deader than Elvis.

There’s plenty of good HK films that prove otherwise even with restrictions.

Well, 2018 was another rather mediocre year for HK cinema as well as HK/China co-ops. Still, sweeping judgements like “HK cinema is deader than Elvis” miss the point. Of course there’s people who stopped caring (or watching), oftentimes those who defined HK cinema to be “action cinema” per se. So yes, it might fly under your radar, but TRUE Hongkong cinema is STILL made; its just that a lot of times it doesn’t stand a chance to be shown in China, so budgets are modest and, well, it usually doesn’t fall into the action/Martial Arts category. Case in point would be SOMEWHERE BEYOND THE MIST and TRACEY, two of the best films I saw last year. And as far as well-made, commercial HK/Mainland joint ventures go, despite its script-related problems I thought PROJECT GUTENBERG was an eminently watchable film.