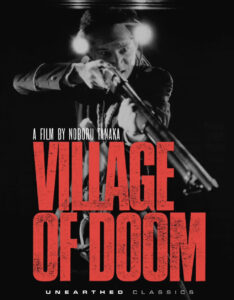

Director: Noboru Tanaka

Cast: Masato Furuoya, Misako Tanaka, Kumiko Oba, Isao Natsuyagi, Midori Satsuki

Running Time: 105 min.

By Paul Bramhall

The Tsuyama massacre remains one of the most harrowing mass murders in Japan, taking place on the night of 21st May 1938 in the rural village of Kamocho Kurami. After cutting off the electricity to the village shortly before midnight, a 21-year-old man named Mutsuo Toi proceeded to arm himself to the teeth, and after decapitating his grandmother with an axe, spent the next 30 minutes murdering 29 of his neighbours (roughly half the villages population), before killing himself at dawn. As a country whose cinematic output isn’t afraid of exploring the darker parts of the human condition, it perhaps shouldn’t be too surprising that, 45 years after the incident, in 1983 it was adapted for the screen in the form of Village of Doom.

What is a surprise is that Noboru Tanaka was chosen as the director, a filmmaker who was most well known for being part of the Nikkatsu studio’s stable of Roman Porno directors, essentially the studios own in-house brand of pink film. With a filmography full of titles like Sensual Classroom: Techniques in Love, Beauty’s Exotic Dance: Torture!, and Pink Salon: Five Lewd Women, Tanaka hardly stands out as the obvious choice to helm a slice of real-life crime that cost so many innocent people their lives. However upon viewing Village of Doom the decision begins to make more sense, and would prove that Tanaka’s talents stretched beyond only helming erotica.

For the lead role Tanaka would cast Masato Furuoya, an actor who’d started out in many of the director’s pink film output during the late 70’s like Female Teacher and Rape and Death of a Housewife. By the early 80’s Furuoya had move onto more indie fare, headlining the likes of 1982’s The Lonely-Hearts Club Band in September, so his versatility as an actor was already well proven. For Village of Doom he plays a studious but naïve member of a small village community who lives with his elderly grandmother, having lost his parents at an early age due to illness. While many of the men in the village have already been conscripted into the military, the call for the academically talented Furuoya has yet to come, and with the village elders being resistant to outsiders, what’s left is a majority of lonely women, and a minority of horny men.

Initially it felt like Village of Doom was a kind of inversion of the 1967 Korean production Burning Mountain, which sees a North Korean army deserter hiding out in a small mountain village where most of the men have gone to war, and how he gradually becomes an object of desire for the women left behind. However while the focus of Kim Soo-yong’s production is told from that of the women, in Tanaka’s narrative the viewer is locked into Furuoya’s point of view. Far from resisting the military conscription, despite being on track for a career as a teacher Furuoya can’t wait for the opportunity to serve the Japanese Empire, and embraces the prospect of going to war. His nighttime studies are interrupted though when another friend clues him in to the after dark goings on of the village, which sees various villagers fornicating with each other regardless of their marital status, or even how closely related they are.

An ancient custom called yobai, it essentially involves the male entering the house of the female, and after giving consent they have sex, after which the man would leave. Basically you could say it’s the original one-night stand. Curiosity eventually gets the best of the virginial Furuoya, leading him to start engaging in the practice himself, and since many of the women are already married and older, he finds himself to be quite the hit. It’s during this stretch that Tanaka’s background as a helmer of pink film comes to the fore, with Furuoya getting it on with a couple of the villagers, and if a viewer wasn’t aware of the stories background, for all intents and purposes Village of Doom looks to play like a typical slice of erotica. Trouble arises though when Furuoya does get called up, only to be told by the military doctor that the niggling cough he’s been suffering from is tuberculosis, a fact which means he’s unfit to serve in the military.

With his dream shattered, things go from bad to worse when he returns to the village to find that word has already spread, and he now finds himself treated as an outcast who nobody wants to go near. Even his cousin, who he shares the closest thing to a romantic connection with, reveals that she’ll be marrying someone else, pushing Furuoya into a deeper and deeper state of anguish and despair. Indeed perhaps the most dangerous element of Tanaka’s interpretation of the events that unfolded on the fateful night is that, by telling them from the perspective of the perpetrator, at no point does Furuoya feel like the villain of the piece. In fact it’s quite the opposite, with his sexual awakening, and subsequent shunning, portraying him as a sympathetic figure who’s a victim of circumstance rather than a horrific monster who killed so many in cold blood.

It’s when he witnesses the village elders assaulting an outsider that Furuoya begins to suspect he’s next in their sights, and decides to take drastic measures to put an end to it. With 20 of the 105-minute runtime dedicated to the massacre, it’s an unflinching sequence that plays out practically in real time, switching alternately between Furuoya’s first person perspective or following him from behind. To his credit Tanaka makes it clear just how premeditated the killing spree was versus a crime of passion, with a scene that shows Furuoya pragmatically gear up, arming himself with a shotgun, katana, a dagger, and a pair of flashlights affixed to either side of his head. By this point he’s past the point of no return and resigned himself to become a demon, one who can achieve his dream of “going to war”, but it’s a war on his own terms with his neighbours painted as the enemy.

It’s a harrowing sequence, with the shaking beams from the flashlights catching the terrified expressions of those whom he’s targeted amidst the darkness, and Tanaka shows a skilled hand at gradually increasing the gore factor as the night progresses, throwing in a couple of practical effect money shots. As the audience there’s a deep sense of discomfort, which was likely the intention, with Tanaka allowing us to get to know Furuoya along with his hopes and dreams for the previous 85 minutes, so it almost feels like the narrative is challenging us to be on side with him in the bloodbath that eventually unfolds. Indeed towards the end of the night, he comes face to face with his cousin who he’d warned to stay away, and when she berates him as a devil he responds that “I’m a devil that got rid of other devils, that’s all.”

Arguably the most disorientating element of Village of Doom is Masanori Sasaji’s synthesiser driven soundtrack, which feels entirely out of step with the period that the story takes place in, and in certain parts wouldn’t feel out of place in a Hong Kong movie from the same era. Far from using the synthesiser to create a dark and foreboding atmosphere, the score is frequently upbeat even during the most harrowing moments, which makes it a welcome but undeniably bewildering choice as to what the intention was. It almost feels like Sasaji was told to score a romantic drama, with no idea what his tracks where actually going to be used for.

As an exercise in adapting a dark moment in Japan’s history Village of Doom ultimately succeeds, taking an uncomfortable subject like a mass killing, and maintaining an impartial lens that stops short of making excuses or glamourising the event. It’ll likely leave you with a slightly confused feeling in your stomach once the end credits roll, which may have been the idea, but what can’t be denied is that it’s a powerful and well-made piece of cinema, anchored by a powerhouse performance from Masato Furuoya.

Paul Bramhall’s Rating: 8/10

You basically came full circle with why the director, of Nikkatsu studio’s stable of Roman Porno projects, was chosen. lol Wasn’t expecting the “sexy” subplot. Good stuff, as usual Paul!