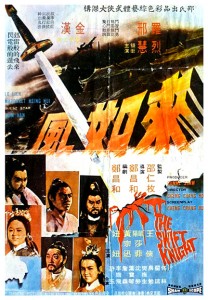

Director: Jeong Chang Hwa

Producer: Runme Shaw

Cast: Lo Lieh, Yau Lung, Chan Shen, Wong Hap, Margaret Hsing Hui, Chin Han, Fang Mien, Chai No, Tung Lam, Wong Chung Shun, Fan Mei Sheng, Hsu Yu, Mama Hung, Lau Kar Wing, Lee Pang Fei, Ou-Yang Sha Fei, Shum Lo

Running Time: 81 min.

By Matthew Le-feuvre

Up to his much lamented death in 2002 from heart failure, former stalwart, international cult icon and introspective celebrity, Lo Lieh will be fondly remembered in martial arts film circles for being cast as perennial miscreats, anti-heroes or unsympathetic characters. Yet, beyond all the demoniacal frowning, sadism and (the) obligatory mocking guffaws, there was so much more depth and refinement to this late star than critics would dare like to admit.

Overworked, underpaid and definitely underrated, Lieh’s frenetic career could almost be perceived as a dereliction of his true creativity in spite of kickstarting the whole “Kung Fu craze” in the West with the enormously influential King Boxer (1972) – better known as Five Fingers of Death – essentially, the first Hong Kong import from the prestigious Shaw Brothers to be marketed and distributed by Warners. Sadly, Lieh never received the credit he was due. He was just another stock-actor in a field of many, defined only as ‘a number’ until executives kept reanimating him like some contractual golem – submissive and robotic to the commands of a studio director (whose sole objective was to be on budget for an expedited release) – and even then, Lo Lieh was constantly overshadowed by the princely leads of David Chiang, Ti Lung and Fu Sheng. These were a handful of reasons why other contemporaries such as Chi Kuen Chun (not to be confused with fellow traditionalist, Chen Kwan Tai) couldn’t wait to escape their legal agreement(s) with the Shaws’.

However, there was a time when Lieh illuminated the jade screen as a hero of chivalrous magnificence, expressing a quiet charm, grace and spiritual enigmatism that was far more appealing in (polar) contrast to his iniquitous behaviour on offer within the narrative of stapled classics: 36th Chamber of Shaolin (1978), Mad Monkey Kung Fu (1979) and Dirty Ho (1979) for instance, as well as the creme dela creme of ethnic prejudice (as) allegorized through the representation of fighting styles; this of course is Wang Yu’s seminal trendsetter, The Chinese Boxer (1970). In it, Lieh apes with cocksure barbarity, as he struts, chops and fly kicks his way through an echelon of brave, but inexperienced mainlanders, leaving behind a pyre of broken bodies while his Japanese accomplices specialize in eye-gouging and dismemberment. Surprisingly, this was a far cry from Lieh’s previous excursion into the mindset of heroic patriotism or, contrarily, self sacrifice in the aid of the exploited.

Here, snarls aside – before Lieh took up the quentessential ‘villian’ mantle full-time – pictures shot and essembled in a similar vein to The Swift Knight (1971) feel innocuous, formal and yet idiosyncratic compared to The Chinese Boxer, and future incarnations such as the demented Chao Chin from The Human Lanterns (1982) or the odious Pei Mei (believed to be a joint catalyst behind Shaolin’s inital destruction). Lieh, naturally, reveled in his portrayal for Lau Kar Leung’s masterpiece Executioners from Shaolin (1977). He later reprised this role for his own version or remake, depending on one’s own perspective. It was a challenge indeed for the Indonesian-born star, but the result, otherwise generally titled in certain territories as Clan of the White Lotus (1980), apparently thrilled packed houses into a frenzy as open mouthed audiences marveled at Gordon Liu’s desperate attempts to find the secret of Pei Mei’s alternating life-force.

For some fans, this was the pinacle of Lieh’s repertoire. After that, the inevitability of typecasting would take precedence over the luxury of personal choices, and nostalgic recalls of Lieh in his heyday would be confined to the ebbing memories of plaudits old enough to be around at a time when Wu Xia was dominant, experimental and downright exhilarating. The Swift Knight, although again ‘essembled’ in that habitual manner we’ve all come too appreciate, lovingly encapulates all these qualities regardless of a patent script, carbon sub-characters or an over familarity with (studio constructed) bamboo forests, isolated taverns, bustling gambling houses or elaborate palace interiors where a corrupt sovereign determines the fates of the working classes. Evocatively, all these nuances are – if one deeply observes – innumerably recycled to the point of being a requisite necessacity.

The Swift Knight is directed by future Lo Lieh collaborator, Jeong Chang Hwa (King Boxer, The Association). This Korean-born filmmaker, unlike the prolific Chang Cheh, wasn’t interested in the theme of brotherhood per se or political metaphors. Instead, his target was to pepper the human senses through simple story telling, less complex action choreography (despite the inclusive tools of wire-work and trampolines) and minimal dialogue; especially from Lieh, who tends too convey his character’s soul through expressionless glares and slow-eye movements. When confronted, he erupts into a balletic dynamo, scything through a barrage of inferior antagonists with ease and majestic presence. His sword, truthfully and quite literally, becomes an extension of himself, eventhough Lieh’s motives are primarily somewhat ambivalent, largely because the screenplay centres around the Prince Regent’s drastic search to eliminate his half brother/sister, Qin Rue and Xian Qin (Margaret Hsing); heirs apparent to the throne.

Interacting with the sibblings (each incognito as lowly peasants), via a shared providence, is Lei Fan (Lieh) aka ‘the swift knight,’ a wanderer who embezzles tax funds from magitrates to finance his solitary lifestyle; a vagabond named Lu Xian Ping (Chin Han), who’s actually a secret service general dispatched to find the heirs and safely deliver them to the Emperor; and a discredited guard (Fan Mei Sheng). Their paths intertwine while pursued by the Prince’s loyal Assassin, Zu Pao, a relentless brute posing as part of an imperial envoy. However, his identity is exposed alongwith the Regent’s inimical ambitions to seize power. It all becomes a deadly race against time, and numerous foes, as the once incongruous trio unite to restore a semblance of political harmony under Xian Qin’s rule.

Verdict: Mixing romance with political intrigue, The Swift Knight richly deserves to be catagorized into that niche of significant landmark pictures: The One Armed Swordsman (1967) or Have Sword will Travel (1969) continually springs to mind for the majority. Sadly, The Swift Knight, unwillingly, for some critics fits into that mould in “Not quite being a classic!” Nevertheless, there is still enough breathtaking imagery: particularly the opening credits of Lei Fan striding across open praries; nocturnal rooftop encounters; as well as kinetic swordplay sequences, featuring Lieh’s almost supernatural deployments against Zu Pao’s impaling projectiles.

Matthew Le-feuvre’s Rating: 7.5/10

This is one of Jeong Chang Hwa’s movies which I’ve still yet to see. You mention he’s a Korean-born director, but actually Chang Hwa is Korean, and spent most of his career working there. By the time he took a contract with Shaw Brothers in ’69, he’d already made over 40 movies. He also directed ‘King Boxer / Five Fingers of Death’ with Lo Lieh, and the pair had previously worked together on ‘Valley of the Fangs’, made a year prior to ‘The Swift Knight’. Chang Hwa eventually left Shaw Brothers and switched to Golden Harvest, during which time he saw out his career directing such classics as ‘The Skyhawk’ and ‘Broken Oath’, before retiring back to Korea.