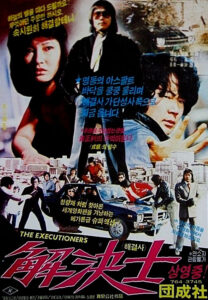

Director: Lee Doo-Yong

Co-director: Godfrey Ho

Cast: Shin Woo-chul, Hwang Jang Lee, Jim Norris, Kwon Il-soo, Min Bok-gi, Park Dong-ryong

Running Time: 90 min.

By Paul Bramhall

It remains one of the greatest travesties in Korean cinema that director Lee Doo-yong’s The Trouble-Solving Broker is referenced in 99% of English language content as “another one of those Godfrey Ho cut and paste jobs.” The real tragedy is that it’s also true, with (as of the time of writing in 2024) no known surviving prints of Doo-yong’s original version in its native Korea, making the re-named Secret Executioners Filmark version that has Godfrey Ho’s name slapped on it as director a double-edged sword. On the one hand its a horrendously modified version of the original – clocking it at 90 minutes compared to the original runtime of 108, which when you factor in the newly inserted gweilo fight footage means there’s likely close to 30 minutes missing. On the other, it’s also the only available way to watch it. The perils of attempting to watch many of the entries in Korea’s taekwon-action genre!

In my feature Fists, Kicks, & Kimchi, I’d stated that “if it’s possible to choose one title which could be interpreted as the last of the ‘pure’ taekwon-action movies, then it would likely be The Trouble-Solving Broker.” Made during an era when the taekwon-action style was increasingly being incorporated into more traditional kung-fu themed settings thanks to the success of 1978’s Drunken Master, Secret Executioners acts as a kind of snapshot of the other direction the genre could have gone in. The 1980’s in general are considered a grim period for Korean cinema, and in 1982 the country as a whole was still reeling from military dictator Chun Doo-hwan strong arming himself into power following the assassination of Park Chung-hee. Fittingly, Doo-yong shifted the taekwon-action genre from the western inspired locales of early 20th century Manchuria to the modern day, often filming guerilla style on the streets of Seoul.

The story focuses on the titular broker (or “the illegal problem solver” as the English dub calls him) played by Shin Woo-chul (Fury in Shaolin Temple, The Supreme Order), looking for all intents and purposes like a Korean version of Columbo, complete with the crumpled beige raincoat and an unassuming demeanour. His services are hired to assist a group of market vendors who’ve been extorted by a gangster running a real estate scam, and who’s backed himself up with a gang of heavies led by fellow broker Hwang Jang Lee (Eagle vs. Silver Fox, Buddhist Fist and Tiger Claws). An acquaintance of Woo-chul who’s less averse to taking on jobs that involve criminal activity, despite sharing a friendship the arrangement puts the pair at loggerheads with the expected results. After their investigations lead them to an acquaintance of the market whose sister has been kidnapped, they’re able to put aside their differences to come to the rescue.

The core of the story for the most part remains, with Godfrey Ho choosing to regrettably incorporate a handful of fight scenes filmed in Hong Kong that utilise the debatable talents of Jim Norris, responsible for the most embarrassing display of snake fist ever committed to film. These scenes involve such highlights as a guy who spits milk whenever he gets hit, insults like “white trash” and “n*gger boy” being thrown around, and most bizarrely – Kwon Il-soo (The Postman Strikes Back, Hard Bastard). Il-soo’s presence is a weird one since he’s also in the original version, so how he got roped (or if he knew he was in the first place!) by Ho into filming the new scenes is one of those great genre mysteries we’ll probably never know the answer to. Their roles give the story a gang rivalry slant, often resulting in narrative confusion, but thankfully there aren’t too many scene insertions (unlike the infamous Ninja Terminator which would come 3 years later).

Despite being responsible for starting the taekwon-action genre with 1974’s The Manchurian Tiger, the last time Doo-Yong had dabbled in the genre prior to Secret Executioners was 6 years earlier with 1976’s Visitor of America (also criminally most well known as its bastardized version Bruce Lee Fights Back from the Grave). In the time since he’d go on to become a critically acclaimed director by helming the likes of The Hut and The Last Witness (both from 1980), and it’s the gritty realism of the latter which also permeates throughout Secret Executioners. The low budget sees Doo-yong frequently filming on the street’s guerilla style, including a frantic foot chase, and much of the story plays out in billiard halls, coffee shops, nightclubs and marketplace restaurants, unintentionally capturing an authentic aura of what Seoul felt like at the time, even with the dubbing.

The same grittiness applies to the story itself, and while Hwang Jang Lee was relegated to being a bit player in almost all of Doo-yong’s early taekwon-action movies, here he’s upgraded to co-star status following his popularity in Hong Kong. Indeed his character here is probably the most fully realised of all his roles – far from turning up to deliver little else aside from sternly worded threats, evil laughter, and his lethal boot work, here we get to see him partake in more menial tasks like getting his hair shampooed in a barber shop, getting it on with a prostitute, and going to a public bath with an acquaintance (source of the much noted HJL posterior shot that seems necessary to point out in any discussion on Secret Executioners!).

It’s the latter setting that also delivers one of the most brutal beatdowns in the boot-masters filmography. Finding himself ambushed in the locker room, Jang Lee proceeds to unleash his kicks against anyone in range, offering up a sense of franticness and desperation which feels far removed from his invincible kung-fu villain roles. The opening Filmark credits list Jang Lee as the fight choreographer, although without the original Korean credits this is impossible to verify, however what’s clear is that Doo-yong seemed to want to make this his taekwon-action swansong and go out with a bang. Fights frequently break out against multiple opponents within confined spaces involving plenty of property damage, and even if some of it feels a little sloppy, the hits feel hard and the choreography leans into the brutality of being kicked or punched in the face.

Woo-chul is a highlight, and as an actor who’s slightly on the burlier side, he energetically throws himself into the kicks he delivers. A standout fight sequence (and the only real one on one) sees him go up against Jang Lee in a knockdown drag out brawl on a beach that segues into an abandoned building, in which they almost bring the entire structure down by kicking out the wooden supporting pillars holding up the rafters. In a latter café set fight scene there’s also an unintentionally amusing moment when Woo-chul delivers a flying kick to a foreigner playing one of the lackeys. After delivering the reaction shot to being kicked he proceeds to calmly stand in the corner, assuming he’s out of shot, until it becomes obvious someone must be frantically signalling him off-camera to move, and he attempts to (failing miserably) subtly exit stage left.

The best is saved for last though, as a literal who’s who in the taekwon-action genre convene in a brick factory for an almost uninterrupted 8-minute mass brawl encompassing fists, feet, steel pipes, knives, spades, bricks (expectedly) and a katana for good measure. Doo-yong even throws in a car driving through a brick wall, as Woo-chul and Jang Lee combine forces to rescue Min Bok-gi (Wild Panther, Strike of the Thunderkick Tiger) and her sister. It’s an entertainingly chaotic and relentless sequence that sees more flying kicks doled out than is possible to count, and everyone goes at it as if their life depended on it. As one of the last times the original era of taekwon-action would grace the screen, Doo-yong ensures that everyone has a moment in the spotlight, and in many ways the scene acts as a precursor to the kind of group brawls that would become a fixture in the gangster genre during the 1990’s and 2000’s.

Despite the Filmark interference Secret Executioner has been subjected to, Doo-yong’s gritty street level vision of Seoul in the early 1980’s and the characters who populate it still shines through. In one particularly gnarly scene a character has their head pushed face first into an unflushed toilet bowl, and as much as I’d consider it a similarly suitable punishment for how Filmark treated so many of the taekwon-action productions, in this case we also have them to thank for being able to see it at all. For that, they can almost be forgiven. Almost.

Paul Bramhall’s Rating: 8/10