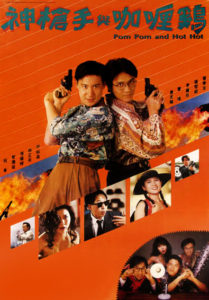

Director: Joe Cheung Tung Cho

Cast: Jacky Cheung Hok Yau, Stephen Tung Wei, Rachel Lee Lai Chun, Alfred Cheung Kin Tin, Austin Wai Tin Chi, Lam Ching Ying, Bonnie Fu Yuk Jing, Ricky Cheung Kwok Leung, Guy Lai Ying Chau, John Ching Tung

Running Time: 90 min.

By Henry McKeand

The early heroic bloodshed films from John Woo and his contemporaries were, above all, Heaven-or-Hell morality tales. These are stories of violent men who fight desperately to hold onto their moral codes and free themselves from fate, hence the word “heroic.” The “bloodshed” occurs because the characters need to escape their tragic destinies. This is what so many Hollywood “Gun Fu” movies failed to understand–the doves and dives and dying only mean something if there are themes of redemption and brotherhood behind it all. In this era of Hollywood action, the earnest reckoning with sin in something like The Killer feels downright alien. In fact, the West was never comfortable with recognizing Woo’s two-handed shootouts for what they really were: cathartic visual metaphors where every bullet was an extension of both the body and the spirit.

How does this take us to Pom Pom and Hot Hot, a largely forgotten Hong Kong action comedy from 1992? Directed by Joe Cheung Tung-Cho, the film centers around characters who are completely uninterested with the basic consequences of violence, let alone the fabric of their mortal souls. The two lead cops, played by Jacky Cheung and Stephen Tung Wai, are happy-go-lucky vessels for broad comedy and buddy movie hijinks. They never seem particularly worried about the ruthless villains, even when their lives are threatened. The movie itself weightlessly moves from one comedic set piece to the next without consideration for theme or tonal consistency.

This makes it all the more surprising that when the movie shifts into an action register, it delivers some of the finest heroic bloodshed style gunplay you’ll ever see. These scattered action scenes are hard to beat in terms of sheer spectacle, but the emotional resonance of Woo’s masterpieces is completely absent, proving that Western filmmakers don’t have a monopoly on borrowing the kinetic flair of Woo’s style while leaving its serious underpinnings behind.

The story starts out promising enough, with our two heroes intervening in a nighttime shootout that leaves several dead. In addition to flying sparks and bursting squibs, there is an impressive amount of graffiti-defying physicality–even bumbling cops can slide on the ground while firing their pistols. Despite the funny dialogue, it’s a genuinely violent first scene, with multiple civilians finding themselves in the crossfire, and Tung-Cho’s direction leaves a strong impression.

The first sign of Pom Pom and Hot Hot’s lack of focus comes in the aftermath of this shootout. The characters immediately forget about the high body count and move on to more “important” matters, such as Cheung’s character being visited by his relatives from the mainland. For the next 50 minutes, this “cop” movie turns into a farce about having to deal with wacky relatives. Even by HK comedy standards, the detour feels egregious.

This isn’t to say that there are no good jokes. The problem is that the movie truly shines when the characters are in motion, and too much of the plot has them standing still and talking. The greatest comedic scene ends in Cheung hanging upside down and kissing his love interest in mid-air, proto-Spider-Man-style. It’s inventive and fun, which is more than could be said for a static, drawn-out scene focused on the apparently hilarious differences between regional styles of Mahjong (though it should be noted that the humor of this scene and many others may have gone over this American’s head).

Simply put, the first hour is a bore. But then, like so many true heroic bloodshed heroes, the final thirty minutes of the film fight like hell to redeem the movie and make up for the mistakes that came before. The cop storyline takes its rightful place as the A plot, and the momentum goes from 0 to 100. Suddenly, the film delivers three back-to-back barn burners that rival the best of 90s HK cinema. The first, involving several characters fighting over a gun in a cramped apartment, is a masterclass in how to incorporate firearms into a martial arts sequence. The next finds the underrated Lam Ching-Ying blasting parts off of a moving car in the middle of a highway. Finally, the climactic gunfight could easily rank as one of the most enjoyably unhinged shootouts in all of moviedom.

The shooting scenes in even the most sober Woo films work like dance numbers in classic musicals–temporary breaks in reality where the laws of physics no longer apply. It makes sense then that the climax of a movie as ungrounded as Pom Pom and Hot Hot would shoot off into the stratosphere. Characters take shots to the limbs like it’s nothing, and the scene gives a visceral punch to its heightened choreography and liberal squib use. There’s very little dramatic weight behind all of this, but it’s a treat to watch.

Soon, the entire world would learn that Woo’s signature style could give a boost to even the most generic action movie. The very same year, Woo himself mixed heroic bloodshed with a straightforward hero cop film in Hard Boiled. Since then, countless movies from around the world (some of which directed by Woo) have proven that highly choreographed gunplay could be easily separated from Woo’s melodramatic narratives. These trendy films could never have the impact of something like The Killer or Johnnie To’s Exiled, but they at least understood that their shootouts were always the best part. If Pom Pom and Hot Hot had realized this sooner, it could have been a minor classic in its own right.

Henry McKeand’s Rating: 6/10