Director: Malene Choi

Writer: Sissel Dalsgaard Thomsen

Cast: Thomas Hwan, Karoline Sofie Lee

Running Time: 85 min.

By Paul Bramhall

Out of all the many characters that frequent Korean cinema, the one which is arguably the most underrepresented is that of the international adoptee. So it came as quite a shock when I watched the recently released Champion, a mainstream production starring Ma Dong-seok as an adoptee raised in the U.S., who returns to Korea both to take part in an arm-wrestling competition (yes, it’s an arm-wrestling movie) and also attempt to find his biological mother. Champion marks the first time for an international adoptee to be the lead character in a Korean movie, with most other examples relegated to either minor roles (Choe Stella Kim in Ode to My Father), or stories that focus on life before the adoption takes place, such as the Kim Sae-ron starring A Brand New Life and Barbie.

The wider issue of international adoption in Korea is a much more complex one. Originally triggered after the Korean War in 1953, the practice is attributed to a gentleman named Harry Holt, who adopted 8 so-called ‘G.I. Babies’ in 1955 after seeing a documentary on TV in the States. However there’s a darker side to Holt’s good intentions, one he could never have been aware of at the time, which is that of Korea’s obsession with racial purity (a facet of their society which, while significantly less prominent than it was 65 years ago, still remains). A huge percentage of the babies adopted overseas, in the years immediately following the Korean War, were fathered to American soldiers who left once the war ended. Usually leaving a mother and child in poverty, the Korean government was happy to offload these mixed race babies back to America.

In the decades that followed things changed a lot. The mixed-race issue faded away as a bi-product of the armistice, and instead most babies put up for adoption were from single mothers, still unfortunately viewed as a source of shame in Korea. With a Confucian society so focused on ancestral bloodlines, domestic adoption has never been much of a viable option, with the concept of raising someone else’s child seen as an alien one. By the mid-1960’s, Korea wasn’t just sending babies to the U.S. but also Sweden, Norway, Denmark, Belgium, The Netherlands, France, Switzerland, and Germany. It became a common quip to say that Korea’s biggest export was babies, and it was only in the mid-80’s that the government looked to start quelling the amount it was sending overseas, with the most recent law putting further restrictions on international adoption introduced in 2013.

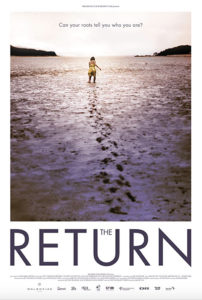

Which brings me to director Malene Choi’s feature length debut with The Return. Choi is an international adoptee raised in Denmark, and has created a unique docu-fiction hybrid that speaks on a level beyond the subject matter on the surface. The loosely structured plot focuses on Karoline, a thirty-something adoptee raised in Denmark, who comes to Korea hoping to track down her biological family. She stays in the Koroot guesthouse, an actual guesthouse in Seoul, dedicated to introducing Korean culture to adoptees wanting to know more about their home country. While there she meets another Denmark raised adoptee in the form of Thomas, also in his thirties, and the pair form a kind of bond as they explore a land and culture which feels completely alien to them.

What makes The Return so unique is that both Karoline and Thomas are not only characters, but rather the actual actors playing variations of themselves. Karoline Sofie Lee and Thomas Kwan are both actors who came to Denmark as children adopted from Korea, and their roles in The Return embody both the directors own experiences, as well as their own, blurring the line between fiction and reality. Blurring the line even further, is that the supporting characters we meet in the guesthouse are actual guests that were staying there at the time of filming, their own stories interwoven into the narrative. This decision gives The Return an inimitable sense of authenticity, with moments of unexpected poignancy often arising out of simple conversations that take place within the comfortable surroundings of the guesthouse.

An adoptee from America explains how he instantly felt at home in Korea as soon as he arrived a couple of years prior, but it strained relations with his adopted family to the point that they asked him to choose between them and relocating there. A lady explains the complete lack of emotion she felt upon meeting her birth father for the first time, while everyone else that was in the room was reduced to tears, but how the opposite happened when she met her birth mother. An artist explains how she uses her experience as an adoptee to create. All have a different story to tell, and while the scenarios themselves are specific to their own experiences, the emotions behind them are relatable to everyone, as feelings of both regret and reconciliation bubble to the surface through their words.

Choi takes a leaf out of Park Chan-kyong’s Manshin: Ten Thousand Spirits in her choice to employ a fictional framework rather than make a full-fledged documentary, allowing for a much broader range of creative freedom than the talking head format would have allowed. The feeling of disorientation that both Karoline and Thomas carry around with them is playfully achieved through both the visuals and sound design, as scenes are rapidly edited together allowing for brief glimpses of someone just walking out of shot, around a corner, or closing a door. Meanwhile playful blips and the sound of a disconnected phone line whir over them, invoking a feeling of disjointedness and dissonance.

Indeed the most awkward scenes in The Return are those that involve the Korean language. Watched on mute it could well look like any other Korean production, however with sound there’s a discomfort in watching Karoline’s attempt to help the guesthouse cook make a meal, who only speaks Korean, as she struggles to maintain the balance between patience and frustration. Only when the common languages of English and Danish are spoken does the tension dissipate, with the scenes between Karoline and Thomas having an air of natural realism about them which is pleasant to watch. At one point Thomas candidly admits that he has much less in common with the other guesthouse adoptees than he expected to, while Karoline is visibly happy to have another Danish person to talk to, leading to both giving the other a small part of what they feel they’re missing in Korea.

Events culminate with Thomas being notified that his birth mother has been located, and that she’d like to meet him the following day. Choi’s handling of the meeting is masterful, opting to forego the easy route of a tearful reunion, instead the meeting begins awkwardly, in a scene that almost feels drowned out by the silence, with only the accompanying translator intermittently translating the odd moments of small talk. Played out in real time, when the questions do finally come up about the past, the emotional weight they carry with them is fully felt, and just like in reality, the full impact of them isn’t felt on Thomas until the meeting is over, and he reaches a decision on what he’ll do with the rest of his time in Korea.

While The Return speaks powerfully to the experience of being an international adoptee from Korea, its triumph really is that it achieves much more than that. For anyone that’s lacked a sense of closure, or sought somewhere to belong, the understanding of the lengths we’ll go to as humans to seek a resolution to such longings, is perhaps what it speaks to the most. In the final scenes Karoline hasn’t found exactly what she came to Korea for, but in the unspoken final moments, it could just be that she’s found something more.

Paul Bramhall’s Rating: 8/10

This sounds like an intriguing film. It’s sad to read about how orphans and adoptees are treated in Korea, but I guess it’s something that westerners can’t understand. It’s almost like how sons are favored more than daughters in Chinese culture.

85 minutes doesn’t seem like enough time for this subject though. I’m sure a lot more could be covered with an extra half hour while respecting the attention span of the audience.