Korea is obsessed with suffering. That is a strong statement but one that is justifiable if you are a fan of South Korean cinema. North Korean cinema could indeed be the subject of its own article with both Kim Jong-un and his father being huge cinephiles, but the films are hard to find and my knowledge of its intricacies is lacking, so I will just stick to the cinema of the South. Of course like any film producing nation South Korea releases a wide range of genres from romantic comedies to historical fiction, however what they have become famous for are hard hitting dramas, revenge pictures and horror. I would argue that horror elements run through the majority of their most famous films and it is what has made them popular with western audiences ever since Oldboy (2003) made everybody take notice of this weird, wonderful and powerful film industry. But what is it about the culture of South Korea that causes them to produce films that regularly contain suffering, revenge and torture and why do so many people enjoy these themes when the majority would agree they are abhorrent.

Korea is obsessed with suffering. That is a strong statement but one that is justifiable if you are a fan of South Korean cinema. North Korean cinema could indeed be the subject of its own article with both Kim Jong-un and his father being huge cinephiles, but the films are hard to find and my knowledge of its intricacies is lacking, so I will just stick to the cinema of the South. Of course like any film producing nation South Korea releases a wide range of genres from romantic comedies to historical fiction, however what they have become famous for are hard hitting dramas, revenge pictures and horror. I would argue that horror elements run through the majority of their most famous films and it is what has made them popular with western audiences ever since Oldboy (2003) made everybody take notice of this weird, wonderful and powerful film industry. But what is it about the culture of South Korea that causes them to produce films that regularly contain suffering, revenge and torture and why do so many people enjoy these themes when the majority would agree they are abhorrent.

Come with me on a journey through the history of Korea and the human psyche!

Like China, Korea had its own Three Kingdoms period starting in 37 BC with the Goguryeo Kingdom, eventually uniting and becoming the Korean Empire in 1897; however this was short lived as the Japanese took over in 1910. This is a major event in defining Korean culture, it was a suppressive and brutal occupation, which forced Koreans to speak Japanese and denied their culture just as it was becoming strong. This lasted until the end of World War Two, but stability was then dislodged again as the country split into the north and south in 1948. Only two years later the Soviet backed North invaded the South and a pointless war ensured which nobody won but over a million people died and many cities were destroyed.

Japanese anime often depicts dystopian futures, largely influenced by the fact they are the only country to have experienced an atomic bomb, whereas South Korea experienced a long period of upheaval and suffering throughout the 20th century, that undoubtedly flavours their own entertainment. This is the beauty of film, it has to be influenced by something so another countries history and culture oozes out of the screen for all to see. National pride is a large part of Korean culture, after being badly damaged by the aforementioned events, it has been slowly restored as South Korea has become rich and prosperous, up there with Japan in producing state of the art electronics. Yet that pain and suffering is still there, bubbling beneath the surface.

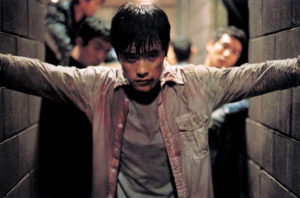

These themes erupted from beneath the surface in 2003’s Old Boy which sees a man locked in a cell by an unknown entity for 15 years and then suddenly released. He then sets out on a path of vengeance to find out why he was imprisoned in the first place. The film quickly gained cult status for a brutally realistic hammer fight in a hall way, our main character eating a live Octopus and its shocking ending. Western audiences were captivated by the intricacies of the revenge plot against our main character Dae-su who discovers that he went to the same school as his captor and had told classmates of the incest happening between him and his sister, resulting in her suicide. Not only was Dae-su imprisoned for 15 years but it is revealed (***spoilers ahead***) that he has been tricked into having a sexual relationship with his own daughter. Such revenge is brutal, meticulous and shows a culture obsessed with honour and an imagination for darkness.

Western audiences certainly had a taste for it too as it gained cult status on DVD, this is also due to the fact that Old Boy is an extremely well made and affecting drama; director Park Chan-wook (now the most famous of the South Korean auteurs) teases superb performances from all the actors, the fact they were unknown to audiences outside of Korea certainly helped the authentic nature of it all. The film is also incredibly tense and has great brooding and dark cinematography, which matches the tone. The Korean language also plays its part, it booms out the characters mouths with a harsh quality making you take notice, and like Japanese it can also sound poetic and alluring.

Old Boy was also released at time in America where subtitles had become the preferred option as people sought an authentic foreign film experience moving on from the hilariously dubbed classic Kung Fu films of the 70’s. Before audiences could recover it was announced that Park Chan-wook was working on a Vengeance Trilogy with Sympathy for Mr. Vengeance 2002 actually released a year earlier but only catching audience’s attention after the emotional hit of Old Boy. With an increasing amount of predictable Hollywood blockbusters the question was: what would he come up with next?

The Vengeance Trilogy is not a conventional trilogy as they are three different films with their own story lines but share a revenge template. Sympathy for Mr. Vengeance is actually more comedic in tone and I would describe it as a serious of silly mishaps, which result in horrible consequences. The story of a deaf mute man who kidnaps a young girl to pay for his sister’s kidney transplant, starts off charming and even ‘cute’ in places but gets increasingly disturbing as accidents and missteps cause a spiral of death and revenge. While not as popular with audiences in the UK and US and a failure at the South Korean box office, it still enjoyed cult status as part of a disjointed trilogy.

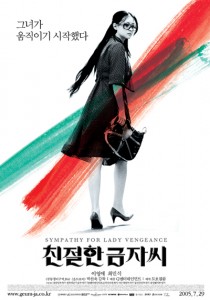

Lady Vengeance (2005) was more popular domestically and is darker than the other two (if that is possible!) as it is entirely focused on the revenge plot of Lee Geum-ja who has been wrongly imprisoned for a child murder and when released on good behaviour vows vengeance on the real killer, an eerily nasty school teacher played by Choi Min-sik who was the star of Old Boy, yet his familiarity doesn’t detract from his performance. South Korean cinema was now officially on the map.

Apart from the skilled craftsmanship of these films why was the darkness so alluring to people? Human nature is a funny thing and we are often most fascinated by what scares us. It is why there are so many documentaries, TV programmes and films concerning serial killers, Nazis and homicide detectives. Very few people would want to experience the actual horrors of these subjects but the ideas contained within them are fascinating. What drives people to commit horrific acts and more importantly can a ‘normal person’ be driven into vengeance or murder?

These questions have been explored by all sorts of media since it began, as it is a part of all our nature. There are also no solid answers that have been found by Science or Religion; does evil exist, are some people born more susceptible or is violence and destruction in us all? Big questions I know! South Korean cinema does not necessarily try to answer them but it does discuss them in a unique and intelligent way presenting the audience with a well thought out scenario that crucially: is hard to predict.

Well, you could gesticulate; of course the Vengeance Trilogy would contain suffering and torture this doesn’t make South Korean cinema full of it! All countries explore dark themes of course; the French gave us a nine minute rape scene in Irreversible (2002), Britain produced the horribly realistic Scum (1979) and Australia gave us a general sick feeling from, scarily based on a true story Snowtown (2011), yet when myself and many others started to explore South Korean films in other genres the same themes kept appearing, as portrayed in the following movies, that are all recommended of course. Starting with tense detective thriller The Chaser (2008) (suffering, torture, unhappy ending) martial arts bloodbath City of Violence (2006) (Suffering, childhood trauma and as the title suggests bloody violence) monster flick The Host (2006) (family suffering, elements of torture and an unhappy ending) and gangster poem A Bittersweet life (2005) (torture, violence and an unhappy ending).

Then of course there is the ode to suffering I Saw the Devil (2010) directed by Kim Jee-woon, which incorporates all these elements for an epic and brutal ride that you will need to watch the entire Disney back catalogue to recover from. The story of an elite police officer whose pregnant wife is murdered by a serial killer again played by Choi Min-sik takes you on his journey of despair and revenge as he decides to hunt and abuse the serial killer, setting him up for a final nasty and humiliating death instead of simply arresting him. It contains all of the above elements but adds cannibals, sexual assault and importantly the concept of honour. As discussed this is a key aspect of Korean culture, which is reflected in their filmmaking.

For a country denied its honour for so long, preserving it is paramount. So why would anyone want to watch this unfurl? Again it’s a brilliantly acted and produced movie but more importantly it makes you confront aspects of life that are inescapable. Tragedy can happen to anyone and when it does, who knows how you would react. The world also contains elements just as dark as those seen in I Saw the Devil (2010) and it is important to remember that and try to make sure you never become part of it, but understand why it happens. Even more significant than that, it makes you appreciate your own life so much more!

Of course as mentioned we all share a fascination with such topics but the South Koreans have had a unique history that was made them free and willing to explore these themes more deeply than other countries. If you’re new to these movies I have either appalled or intrigued you, perhaps both, which I think is the strategy of directors like Park Chan-wook who made his English language debut with the vampire themed Stoker (2013) or Kim Jee-woon who did the same with bloodier than usual Arnie actioner The Last Stand (2013). This shows the crossover appeal of these directors and their movies, proving that we are all deviants, willing to indulge in a slice of violence, suffering and the dark side of humanity; but when it comes to realising it on screen the South Korean’s are the experts.

What we all learn from Korean movies is to never, EVER piss off a Korean person.

Great article. It really makes me think about my complicated relationship with Korean cinema.

I love Korean movies, but then some of them feel like they were made as a middle finger to audiences.

The Vengeance Trilogy may not be happy movies, but I felt there was a point to it, and that the human elements were more important than the shocking parts. With I Saw the Devil, that movie felt like if Seven was made as a 70’s exploitation flick.

When Choi Min Sik was with his victims, the way the scenes were directed and how camera lingered on the women felt like the movie was trying to make the scenes erotic. I understand they’re presented from Min Sik’s point of view, but it felt unneeded.

Movies can’t always have happy endings, but I feel like if a downbeat ending is presented, there should be a point to it instead of having it for the sake of having it.

“With I Saw the Devil, that movie felt like if Seven was made as a 70’s exploitation flick.”…

I always thought of I SAW THE DEVIL as an action version of 007-meets-Seven if Kim Jee-woon directed it (wait, he did! lol)

Despite having Jung du-Hong as action director, it didn’t seem very action driven. I’m sure 007 wouldn’t bother playing with the murderer like a kid pulling wings off of flies.

Hi Andrew,

Thanks for the comment, glad you enjoyed the article. I see exactly what you are saying, I Saw The Devil is overly harsh in a way only the Korean’s can deliver.

But I would argue there is a point to it all. The clue is in the title. Initially Lee Byung-hun’s character sees the devil and ultimate evil in Choi Min- sik, as he is so despicable he feels that a prison sentence or even a quick death is not enough, and after all the pain he inflicts, he starts to see the devil in the mirror. How do we punish those that are beyond redemption without becoming a monster is the question?

We could of done without the shot of him scraping through his own faeces though!

Thank you as well. I certainly see that aspect in how Lee becomes the very thing he hates. It was also tough to watch though because I felt like the audience is supposed to be on his side until the end, but the moment he let Choi hurt more people early on, my sympathy ended.

But my pain problem was the movie “eroticising” Choi’s victims. That becomes less about suffering as an art, and makes the movie look more like a “pink” film for the raincoat crowd.

A very entertaining and well written feature! For a Korean film fan like myself it was a pleasure to read. A few of my own thoughts below –

“This is a major event in defining Korean culture, it was a suppressive and brutal occupation, which forced Koreans to speak Japanese and denied their culture just as it was becoming strong.”

Not only that, but they also had to take on Japanese names. A great movie to watch which covers this exact subject, is Im Kwon-taek’s 1978 film ‘Jokbo’. The plot follows a Korean worker, employed by the Japanese to ensure the population is complying with the name change policy, and his encounters with a particularly stubborn family man who refuses to do so.

“Starting with tense detective thriller The Chaser (2008) (suffering, torture, unhappy ending) martial arts bloodbath City of Violence (2006) (Suffering, childhood trauma and as the title suggests bloody violence) monster flick The Host (2006) (family suffering, elements of torture and an unhappy ending) and gangster poem A Bittersweet life (2005) (torture, violence and an unhappy ending).”

Solid choices! For me I’d just stop short of declaring the movies you’ve cited as having ‘unhappy endings’. Unconventional endings for sure (part of their charm), and some of the characters (sometimes even the main one!) could be argued to have unhappy ends…but if that gives the movie itself an unhappy ending is a questionable one. By Hollywood standards of course it’s an easy ‘yes!’, but from the perspective of the world these movies take place in, maybe not.

**SPOILERS AHEAD*** In the closing scene of ‘The Chaser’ Kim Yun-seok’s character finally reconnects with his humanity, in the small but subtle gesture he shares with the victims child, indicating that he’s rediscovered a part of himself long thought lost. In ‘The Host’ the family takes in the child that survived the ordeal with the monster, showing their solidarity and kindness as a family unit, even after all they’ve been though. In ‘A Bittersweet Life’ Lee Byung-hun’s character, after serving his whole life as an enforcer to a ruthless gangster, finally finds a good cause to fight for (the love between the gangsters moll and her secret boyfriend), giving some meaning to his life even if it means losing it in the process.***END OF SPOILERS***

“It contains all of the above elements but adds cannibals, sexual assault and importantly the concept of honour. As discussed this is a key aspect of Korean culture, which is reflected in their filmmaking. For a country denied its honour for so long, preserving it is paramount.”

This is an interesting take. For me I’ve always thought that Korean movies excel in the art of portraying revenge, but rarely have I thought that the revenge in question incorporates a concept of honour. Particularly in the example mentioned, ‘I Saw the Devil’, I’d say Lee Byung-hun’s actions are anything but honorable. He’s so consumed with revenge that he can’t see the wood for the trees (a shortsightedness that ultimately **SPOILER** has his actions lead to the grizzly murders of both his wife’s sister and father **END OF SPOILER**). Honour for me somehow brings to mind images of righteousness and morality, whereas many of the characters in Korean film are only seeking vengeance, and are willing to get their hands very dirty to get it.

“Park Chan-wook who made his English language debut with the vampire themed Stoker (2013)”

I’m curious to know what you mean by ‘vampire themed’?

Look forward to your next piece!

Hi Paul,

Thanks for the feedback, beautifully illustrated I think you have shown why South Korean Cinema is popular, as it isn’t as simplistic as just an unhappy ending for the protagonists, however I would still stick with either unhappy, depressing or at least melancholic for films such as A Bitter Sweet Life or The Chaser but you are right there is much more going on in these movies.

Apologies, I confused Stoker with 2009’s Thirst, which is the same director and ‘vampire themed’.

I am going to go and watch some of these films again now! If anyone has any recommendations of films, that are not mentioned in the article feel free to comment below.

Agreed! They’re certainly not movies that you walk away from with a big smile on your face, that much is for certain. Cheers for the clarification on ‘Stoker’ as well, I’d concocted some far flung theory that you somehow thought it was a biography of Bram Stoker, the author of Dracula. 😛

Regarding recommendations, in terms of movies that fit the theme and I personally rate very highly, I’ll rein myself in at 15 and go with –

Hole (1997)

No Mercy (2009)

The Yellow Sea (2010)

Confession of Murder (2012)

Man on High Heels (2014)

A Girl at My Door (2014)

The Shameless (2014)

Coin Locker Girl (2014)

Gangnam Blues (2015)

Inside Men (2015)

The Truth Beneath (2015)

Missing You (2016)

The Wailing (2016)

The Villainess (2017)

Asura: City of Madness (2017)

*Click on the titles to be taken to the review